A clock strikes thirteen. A black-bellied spider envelops a room in streamers of red silk. An anti-corporate revolutionary is tortured to death, her flesh transmuted to gold through some perverse hyper-science. The barrier between human reality and dimensions unknown wears thin, and a pallid young man dressed like Percy Shelley pilots a horse-drawn carriage through the rift. This dark-clad stranger manifests in multiple places simultaneously, including the Persona Century main office, an orbital space station the size of a city, and in the wreckage of Kabuki-cho, one of the few remaining freeholds on an Earth enslaved by a monolithic corporation.

Welcome to Darkside Blues, a 1994 animated film based off of a short story and a manga penned by Hideyuki Kikuchi (Wicked City, Demon City Shinjuku, A Wind Named Amnesia). Buckle up; it’s going to be a bumpy ride.

Welcome to Darkside Blues, a 1994 animated film based off of a short story and a manga penned by Hideyuki Kikuchi (Wicked City, Demon City Shinjuku, A Wind Named Amnesia). Buckle up; it’s going to be a bumpy ride.

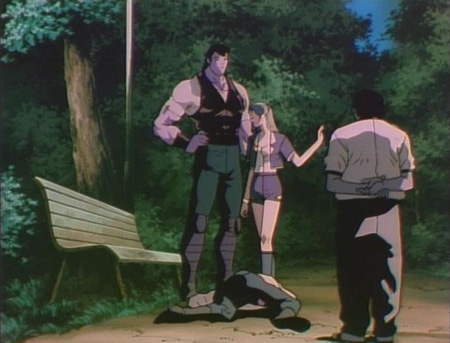

The first time I saw Darkside Blues over thirteen years ago, I didn’t know what to make of it. Darkside Blues is a strange film, but not strange in the Angel’s Egg sense. Darkside Blues tries to tell a straightforward narrative: in the indeterminate future, the Persona Century corporation owns nine-tenths of the world’s labor, land, and resources. Opposing Persona Century’s hegemony are scattered bands of anti-corporate guerrillas known as the AP-Men, as well as the dissidents, street gangs, and other rabble walled off from the rest of the world by the barriers surrounding what’s left of Shinjuku. A failed terrorist attack on Persona Century’s main office and the appearance of the mysterious Darkside spur the mega-corporation to mobilize its forces in Kabuki-cho, and when the last surviving member of the anti-Persona terrorist team enlists the aid of the formidable Messiah gang, trouble follows.

Despite this premise, Darkside Blues is more concerned with atmosphere than weaving a coherent story; it defies numerous narrative conventions in favor of evoking a world where high tech and low life collide with magic and Eastern mysticism. Genetically enhanced assassins, combat robots, and orbital laser cannons coexist alongside psychic powers and techno-spiritual weirdness. The titular character, Darkside, is not even the protagonist. He’s the embodiment of Yin, the passive principle, and a sort of psionic surgeon. When he acts at all, Darkside directs his tremendous psychic power into feats of rejuvenation that treat the wounds on his patients’ psyches with the tender caress of darkness.

Instead, the main character is Mai, the leader of the Messiah gang, voiced in the Japanese by Kotono Mitsuishi. I’m stunned by the parallels between Mai and another, more famous character that Mitsuishi portrayed: Misato Katsuragi in Neon Genesis Evangelion. Like Misato, Mai is a strong-willed young woman in a leadership position that’s also a high-functioning alcoholic. Also like Misato, Mai’s blustery exterior conceals the scars of her past. But unlike Misato, we never learn the exact details of what’s tormenting Mai. Her relationship with Guren, the heir-apparent of the Mizuki clan, is difficult to scrutinize. Was Mai a victim and Guren a perpetrator, as the film initially implies? Or were they lovers once, and was Guren’s betrayal something more basic, as implied by the business with the locket and Darkside probing their respective memories with his psychic powers? Where does the truth reside? We can’t be absolutely certain, and this moral ambiguity, this spiritual malaise, is a defining characteristic of anime adaptations of Hideyuki Kikuchi’s work.

Instead, the main character is Mai, the leader of the Messiah gang, voiced in the Japanese by Kotono Mitsuishi. I’m stunned by the parallels between Mai and another, more famous character that Mitsuishi portrayed: Misato Katsuragi in Neon Genesis Evangelion. Like Misato, Mai is a strong-willed young woman in a leadership position that’s also a high-functioning alcoholic. Also like Misato, Mai’s blustery exterior conceals the scars of her past. But unlike Misato, we never learn the exact details of what’s tormenting Mai. Her relationship with Guren, the heir-apparent of the Mizuki clan, is difficult to scrutinize. Was Mai a victim and Guren a perpetrator, as the film initially implies? Or were they lovers once, and was Guren’s betrayal something more basic, as implied by the business with the locket and Darkside probing their respective memories with his psychic powers? Where does the truth reside? We can’t be absolutely certain, and this moral ambiguity, this spiritual malaise, is a defining characteristic of anime adaptations of Hideyuki Kikuchi’s work.

And what of the world that Darkside Blues depicts? Despite the spiritual elements and the psychic warfare, the closest comparison I can draw is the Sprawl Trilogy by William Gibson. Persona Century is run from orbit by the decadent Hazuki clan, analogous to the Tessier-Ashpools of Neuromancer and Mona Lisa Overdrive. A limitless landscape of corporate arcologies surrounds the decaying Shinjuku, which is walled off from the rest of world like a cyst. Darkside Blues paints a portrait of beautiful desolation that is often more intriguing than the struggles of the characters within the film.

Watching Darkside Blues is an experience both pleasing and bewildering. Its animation is gorgeous and its plot is compellingly strange, and there are brief bursts of violent action that make me want to stand up and cheer. But the film is also unrelentingly obtuse; it refuses to give the audience the sort of closure moviegoers have come to expect. When the credits roll, the guerillas are still fighting for freedom, and Persona Century still has its jackboot firmly planted on the neck of the populace. Darkside muses of new things waiting to be born from the darkness, but what these things may herald for the future of this world is never addressed. It’s like watching the middle part of a trilogy, without the knowledge of the beginning or the promise of a conclusion, so while I enjoyed Darkside Blues, I’d be hard-pressed to recommend it to the casual viewer.

Watching Darkside Blues is an experience both pleasing and bewildering. Its animation is gorgeous and its plot is compellingly strange, and there are brief bursts of violent action that make me want to stand up and cheer. But the film is also unrelentingly obtuse; it refuses to give the audience the sort of closure moviegoers have come to expect. When the credits roll, the guerillas are still fighting for freedom, and Persona Century still has its jackboot firmly planted on the neck of the populace. Darkside muses of new things waiting to be born from the darkness, but what these things may herald for the future of this world is never addressed. It’s like watching the middle part of a trilogy, without the knowledge of the beginning or the promise of a conclusion, so while I enjoyed Darkside Blues, I’d be hard-pressed to recommend it to the casual viewer.

Originally released by Central Park Media, Darkside Blues has been rescued from the darkness by Section 23. So if your tastes gravitate toward the Gothic, the cyberpunk, or the surreal, you can reach across the tortured psycho-space of the Internet and order this title for yourself. Be warned, though: it just might end up imprisoned for decades in your own personal Vault of Error.

Distributor: Section 23 Films

Originally released: 1994

Running Time: 83 minutes

©1994 Akita Shoten • Toho Co., Ltd. • J.C. Staff

![Demon City Shinjuku [Anime Review] Demon City Shinjuku [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/demoncity_shot11-480x360.jpg)