A little over a decade ago, everyone was trading fansubs of Kimagure Orange Road. In 2002, I borrowed a milk crate of VHS tapes from a friend and watched my way through the 1987-1988 TV series, followed by Kimagure Orange Road: The Movie.

Fast forward to today, when it’s been left to me to write something about the series because Daryl Surat has claimed, in the magazine and here, that “…KOR was probably the direct predecessor to the modern ‘harem’ anime genre, while Tenchi [Muyo] was its first fully realized, non-subversive iteration of it.” He later claimed he’d never used the word “subversive,” and said “anti-harem” instead. I’ll get back to Daryl’s theory in a moment.

By way of a disclaimer, I have not revisited KOR for the purposes of writing this article. For one thing, it’s 48 episodes long, with two movies and an eight-episode OVA series. Frankly, writing Shelf Life for ANN takes up all my non-Game of Thrones time. That, and I liked KOR when I first watched it. (I also refuse to revisit ThunderCats as not to destroy my childhood nostalgia.) Re-visiting KOR after a decade of harem anime and weak ero-com titles might ruin my enjoyment.

By way of a disclaimer, I have not revisited KOR for the purposes of writing this article. For one thing, it’s 48 episodes long, with two movies and an eight-episode OVA series. Frankly, writing Shelf Life for ANN takes up all my non-Game of Thrones time. That, and I liked KOR when I first watched it. (I also refuse to revisit ThunderCats as not to destroy my childhood nostalgia.) Re-visiting KOR after a decade of harem anime and weak ero-com titles might ruin my enjoyment.

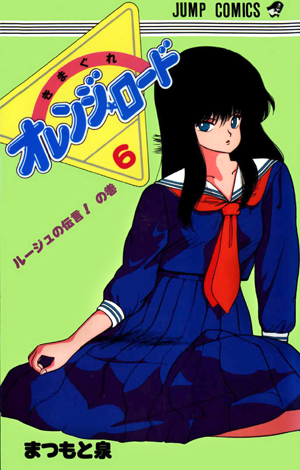

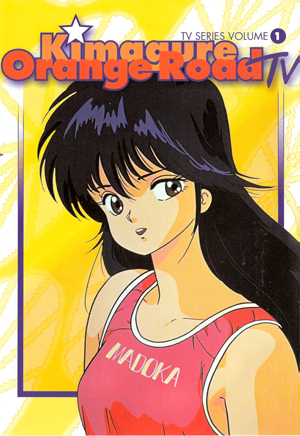

So what is KOR about? Fifteen-year-old Kyosuke Kasuga moves to a new town and falls in love with a girl named Madoka the day before school starts. Madoka is a former long-skirted delinquent “yankee” type who sometimes still gets into fights using a guitar pick as a (startlingly effective) projectile. Meanwhile, a bubbly, kind-hearted girl named Hikaru falls for Kyosuke and they more or less start dating. Despite being certain of his feelings, Kyosuke can’t bring himself to dump Hikaru and go out with Madoka. The tension in the series comes from Kyosuke’s inability to move forward.

Oh, and Kyosuke’s entire family has psychic powers. The psychic abilities aren’t terribly important to the series outside of being an excuse for zany plotlines and a source of gags. The first movie drops the powers completely, as if to acknowledge that no one was watching KOR for the psychics in the first place, it just happened that psychic manga and anime was a huge genre of that time period.

KOR bends over backwards to give the viewer an intimate, sympathetic look at a boy’s first love and first feelings of sexuality (towards a real girl, and not an actress or an image in a magazine). A significant portion of the show is spent with lingering camera shots cutting back and forth between Kyosuke’s eyes and Madoka’s lips and/or cleavage. Sometimes it’s funny, sometimes it comes off as creepily voyeuristic, and other times the sequences just seem honest. This is a romantic comedy from a boy’s point of view, primarily for a male audience (which isn’t to say girls can’t enjoy it, too). The manga originally ran in Weekly Shonen Jump.

I watched every last one of the 48 episodes waiting for Kyosuke to make his move. The TV series never fully resolves, and instead, you have to watch the movie to get some closure. The movie is a very serious film about a break-up. The girl who ultimately gets jilted (and I won’t say which one) goes through a series of very realistic emotional stages post-break-up. It’s very touching, and very true to life. The film is an emotional journey that I could totally identify with (having been dumped in the past myself), and although I loved the movie, it’s so moving I don’t think I could re-watch it with any frequency.

I watched every last one of the 48 episodes waiting for Kyosuke to make his move. The TV series never fully resolves, and instead, you have to watch the movie to get some closure. The movie is a very serious film about a break-up. The girl who ultimately gets jilted (and I won’t say which one) goes through a series of very realistic emotional stages post-break-up. It’s very touching, and very true to life. The film is an emotional journey that I could totally identify with (having been dumped in the past myself), and although I loved the movie, it’s so moving I don’t think I could re-watch it with any frequency.

In fact, I found the first KOR movie so satisfying that I never watched the second one, which un-does some of the first. I dabbled in the OVA series, which includes psychic powers again, but they seemed so after-the-fact I never finished watching them. After you see the movie, the dramatic weight is gone.

For my money, KOR isn’t anything close to a harem series. It’s a love triangle. (Disturbingly, the only other love triangle show I can name off the top of my head is Onegai Twins.) KOR is hardly more of a harem than Marmalade Boy. That is to say, new competitors for Kyosuke’s love sometimes appear, but unlike in a modern harem series, they don’t end up living at his house.

Daryl labels the main examples of historic harem anime as “anti-harem,” namely, Urusei Yatsura and Ranma 1/2. I think both shows are at least better examples of proto-harem series than KOR.

In Urusei Yatsura, a bodacious alien babe named Lum comes to Earth, and after a series of unlikely events lays a marriage claim on the jerktastic Ataru. Ataru is ironically interested in every girl except Lum, who comes to live at his house and punish him with her Pikachu-like zapping ability. Unlike in most contemporary harem series, Lum’s physical abuse is usually well warranted by Ataru’s lecherous actions. More aliens and crazy characters arrive on the scene as the episodes go by.

In Ranma 1/2, title character Ranma is betrothed to Akane, but both teens are stubborn, and too busy dealing with gender stereotypes to admit that they like each other. Because Ranma changes gender when doused with water, he collects suitors of both sexes he has to run from. New love interests appear in almost every episode who want to marry Ranma, but unlike in modern harem series, they do not come to live at Ranma’s house. Despite the large number of suitors, only two (or three, if you include Shampoo) are serious contenders.

Why Tenchi Muyo is the predecessor of the modern harm has everything to do with his personality. Tenchi is a blank slate, a sort of good-natured unassuming proxy for the viewer. Ranma and Ataru have distinct personalities, are decisive, and are unashamedly interested in girls. “I called UY an anti-harem show since the girls hate the main male lead character who has a very distinct personality,” Daryl says, “Similarly, Ranma Saotome isn’t a blank slate sort of character, and not all the girls in the show want to get with him.”

Why Tenchi Muyo is the predecessor of the modern harm has everything to do with his personality. Tenchi is a blank slate, a sort of good-natured unassuming proxy for the viewer. Ranma and Ataru have distinct personalities, are decisive, and are unashamedly interested in girls. “I called UY an anti-harem show since the girls hate the main male lead character who has a very distinct personality,” Daryl says, “Similarly, Ranma Saotome isn’t a blank slate sort of character, and not all the girls in the show want to get with him.”

Daryl goes on to say, “[Harem series] didn’t go full bore until the KOR and Tenchi stuff, where the main character has no particularly distinctive physical features or personality traits aside from ‘won’t attempt to decide which girl to screw until the very last episode.’ You the viewer can easily substitute yourself in for this bland, featureless cipher.”

I disagree that Kyosuke is a featureless cipher. He seems more like an “everyman” to Tenchi’s “any-man.” Tenchi Muyo lacks the dramatic weight of KOR as Tenchi never appears to struggle with making a decision between suitors, whereas Kyosuke is already dating one girl from the outset (he chose one girl and kind of regrets his choice). Tenchi also rarely seems interested in sex, whereas Kyosuke is more than just interested in girls, he’s going through his own personal Spring Awakening. In some respects, the viewer is meant to ogle at Madoka and Hikaru through Kyosuke’s eyes, but he seems more like a vehicle for the viewer’s realistic nostalgia than Tenchi. It’s more, “oh to be young and in love! [and also a psychic]” than, “oh to be young and have eight space princesses living at my house!”

In fact, the modern harem anime is often far removed from reality, to the point of including many non-human girls. Sekirei is a great example, where magic-fueled non-human buxom babes fight it out in an alternate reality. By contrast, the women of KOR have realistic teenage bodies and, despite the ESP, the show has its feet firmly on the ground. In other words, at least Madoka’s boobs are realistic.

AnimEigo put out a DVD boxed set in 2004, but it can be a little expensive and hard to come by lately. There’s a rumor on Wikipedia that the manga will be released electronically in the near future.

![Lady Oscar: The Rose of Versailles [Anime Review] Lady Oscar: The Rose of Versailles [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/RoV_Vol2_Front_CoverArt_V1-480x360.jpg)