I frequently bemoan the fact that Studio Ghibli, despite its status as the single most prestigious anime studio of all, has trouble cultivating new creative talent beyond its principal founding members. But I kind of understand why they became that way. It’s because of I Can Hear the Sea, their most lackluster film in comparison to everything else they’d done until Tales from Earthsea came along.

Also known as Ocean Waves—please note there are almost zero actual ocean waves in this film as the story really has no relevance or proximity to any sort of large body of water at all such that the title is metaphorical at best—I Can Hear the Sea was a made-for-TV movie that debuted on Christmas day back in 1993. It marked the very first time a Studio Ghibli film was made in which neither Hayao Miyazaki nor Isao Takahata were directly involved. In an industry so famously dominated at the top by middle-aged to senior-aged men, the idea behind the project was that the young up-and-comers at the studio, those in their 20s and 30s, would make their own movie to show that they, too, could come up with their own ideas and successfully manage their own projects within a reasonably modest budget. In other words, it’s exactly the sort of thing all anime studios should be doing to help guarantee their futures. A success here would demonstrate that the apprentices were capable of stepping out from the shadow of the masters.

Unfortunately, it didn’t exactly succeed in those regards. The project wasn’t finished in time, it ended up costing more than what was originally allotted, and worst of all the story and characters were utterly derivative and formulaic even 20 years ago. That we’re still seeing characters and situations exactly like this play out in modern anime productions is a topic for another day, but Studio Ghibli’s output throughout the 1990s was literally without peer in the anime world. The animation work they were producing was unlike anything being done by anybody else, so for them to make something so cookie-cutter, so “like other anime,” was a huge letdown for me. I’m sure it was an even bigger letdown for Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, who seemed to unofficially declare “you had your chance and you blew it, guys. From this point on, nobody is allowed to direct movies here except for us.” So that edict has largely remained in place for years and years, even when subsequent efforts by new directors actually turned out to be pretty darned good. Perhaps it’s a case of “once bitten, twice shy”?

Both I Can Hear the Sea and Ghibli’s more recent From Up on Poppy Hill alike are adapted from prior source material that was originally targeted toward girls. Both of them also have points where the male lead verbally states “this is like a cheap melodrama” and are in the right to do so. But unlike Poppy Hill, this film is not set in “the past” and the coming-of-age romantic elements are far more prominent. The applicability of that line to the overall narrative is subsequently that much greater. I hate using the word “angst” in reviews about as much as I hate anime that exude that emotion from their celluloid pores—sorry, Marmalade Boy fans!—but there are few other words that aptly convey the overall sentiment here.

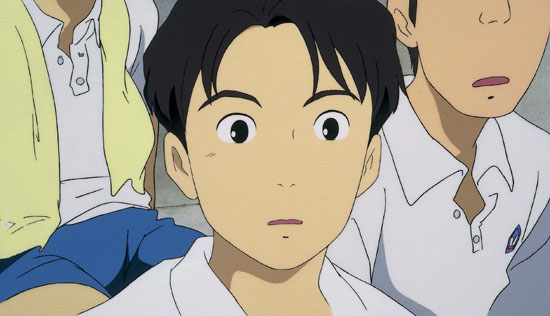

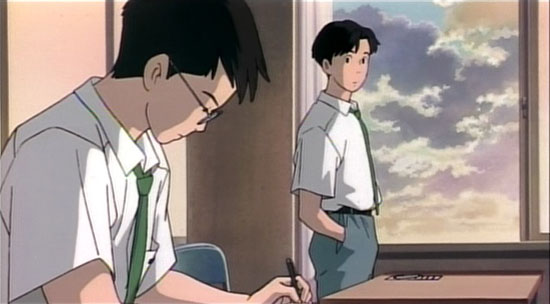

Told in the form of a flashback to “two years ago,” I Can Hear the Sea is set in your typical “Anime High School” out in a more suburban area of Japan. Taku Morisaki, our main character, is your typical generic male “romantic anime” protagonist in terms of appearance and personality. If you can think of Kyosuke Kasuga from Kimagure Orange Road (minus the psychic superpowers), or Yusaku Godai from Maison Ikkoku you’ll have the right idea. If those references are too dated, suffice to say he’s a pretty generic “everyman” sort of character to which “the average person” is ostensibly supposed to relate. Taku is best friends with the bespectacled Yutaka Matsuno, and has been friends with him since junior high. Then the new girl from Tokyo transfers into class, and if such a rule ever existed about what bros supposedly are to come before it’s fated to be tossed to the wayside.

We’re repeatedly told that Rikako Mutou is beautiful beyond compare, even though she looks roughly similar to the other girls in the film. In a lot of ways, she’s effectively Ayukawa Madoka from Kimagure Orange Road: annoyingly perfect both in academics as well as sports, with a rich family and absentee parents that result in her living alone, who is coveted and desired by all despite being completely and utterly unlikable. Both Morisaki and Matsuno take an interest in her, and during a high school summer trip to Hawaii—also straight out of Kimagure Orange Road, except this time there are no kidnappers threatening in awful English to feed them to the sharks—she manipulatively cons Morisaki into “lending” her several hundred dollars to replace the cash she “lost”… after cozying up to Matsuno, whom she then “borrows” ANOTHER few hundred dollars from.

There’s a word to describe people like Mutou, and that word is “sociopath.” She’s ultimately just using everybody she pretends to be friends with as part of a grander scheme on her part, and every time Morisaki finds out he’s been duped and goes to angrily confront her, she puts on the forlorn sob story act and convinces him to go along with it even further. Even if it’s something like getting on a plane and flying to Tokyo with her for several days without telling his parents where he’s going. And he acquiesces because she’s…pretty? I guess? Is this supposed to be a youthful discrepancy for which we are to empathize with or something?

Morisaki eventually parts ways with Mutou and checks into a hotel room before heading back home the next day. But wouldn’t you know it, she then shows up to the room he’s staying in, runs crying into his arms, and starts chugging rum and cokes… because it turns out the wallpaper in her room got CHANGED to a color she doesn’t like, and the kitchen pots are now ENAMELWARE. Gee, no WONDER she’s upset! She then passes out on the bed, which means that Morisaki must now sleep in the bathtub of his own hotel room because this is still a Studio Ghibli movie released on Christmas day. Then in the morning Mutou meets her ex-boyfriend for coffee and uses Morisaki as a stand-in prop. See, Mutou’s ex has a new girlfriend and there is NO WAY she can’t also be seen as not having gotten a boyfriend since.

Here’s the other sign of sociopathy: the instant Morisaki’s no longer useful to her, Mutou never speaks to him again. Next thing you know, the whole school knows about how these two flew out to Tokyo and spent the night at a hotel. You know why? Yep, it’s because she tells everybody. This all obviously drives a huge wedge between the friendship of Morisaki and his best friend Matsuno, whose high school (and college, and entire life) prospects suffer for it. Nothing ends well for anybody, and the whole time everything is presented as though we’re supposed to think of Mutou as “the dream girl.” The only dream I would have of Mutou is her being introduced to Keiji Mutoh. A couple of well-placed Dragon Screws and Shining Wizards would have done this story a great service.

Clocking in at a mere 75 minutes before commercials, I Can Hear the Sea feels three times as long. The soundtrack doesn’t help either, since it only has maybe one or two motifs throughout the entire running time. For years I thought there was just one solitary song set to repeat. It’s not by longtime Ghibli composer Joe Hisaishi but rather Shigeru Nagata, who just prior to this had worked on the OVA adaptation of Here is Greenwood. I LIKED that… until the last two episodes. I Can Hear the Sea feels a lot like the final two episodes of Greenwood, which in turn felt an awful lot like Kimagure Orange Road the same way this does… and that’s because all of them were directed by the same man: Tomomi Mochizuki, a man who had also handled the anime adaptation of Maison Ikkoku and the first season of Ranma 1/2 before working on this.

Put aside the fact that a lot of those are considered enduring classics of anime. The thing to keep in mind is that by 1993, there was absolutely no shortage of this type of story or these types of characters and “coming-of-age love triangle” situations in anime. Having such subject material covered in animation was of course unheard of in America back then, but at this point it’s all been recycled so much over the decades that even we in American anime fandom now have specific terms to describe characters like Mutou that seem outwardly hostile and distant, but deep down are sensitive and vulnerable. I keep going back to Morisaki’s expression aloud that it all feels like a cheap melodramatic soap opera, but it’s because he’s right on the money: they actually made a live-action TV movie out of this, and it manages to be even worse. At least the animation in this film still LOOKS the part of a Studio Ghibli title, thanks in large part to Katsuya Kondo’s character designs. Kondo has done tons of Ghibli’s character designs, including From Up on Poppy Hill‘s. You know that “Studio Ghibli character” look? He has a lot to do with that.

It’s not like I have an axe to grind with Tomomi Mochizuki. To be sure, there are a fair share of clunkers in his résumé (he did Dirty Pair Flash, for instance), but he has and continues to do good work. For one of his more recent notable efforts, take a look at the noitaminA series House of Five Leaves. That doesn’t exonerate this, though. From the late 1980s until the late 90s/early 2000s, Studio Ghibli had the reputation of being pioneers in the realm of animation. That’s why whenever I see that “Studio Ghibli” logo I expect to see something unlike anything else in anime, such that anything short of that is a disappointment. Ghibli wasn’t the place for treading on past successes, producing content that was awfully similar to, yet not quite as good as, the previous ones they had already made in years prior. No, that came LATER.

Even though it has never been released in the US, the passage of time may be why I Can Hear the Sea just might have more supporters now, in 2013. As the heads of Studio Ghibli continue to age and grow disillusioned, having the movie open with that blue screen and that Totoro pencil drawing is no longer the unassailable bastion of innovation and quality it once was. Perhaps supporters of this movie are out there, right now, waiting to pounce in the comments section to tell me “oh come on, this wasn’t THAT bad.” And maybe, just maybe, they’re right. But I Can Hear the Sea was preceded by what I consider to be Isao Takahata’s best film of all time, Only Yesterday, as well as what just might be Hayao Miyazaki’s best film of all time, Porco Rosso. (Depending on what day you catch me, I tend to go between that and Princess Mononoke.) Any way you slice it, to go from movies of such a caliber as those to I Can Hear the Sea is just too steep a quality drop, even if you DO think this is “not that bad.” Mediocrity, even “above average,” just isn’t good enough for the place whose reputation is staked on the fact that they are the best of them all. But that still doesn’t mean the powers that be at Studio Ghibli were right to be so restrictive in terms of creative control and project management in the 20 years since. I have no idea what’s going to become of the studio after Miyazaki and Takahata each release their new, and likely final, movies soon. But I sure hope they don’t end up making more anime like this one.

![Lady Oscar: The Rose of Versailles [Anime Review] Lady Oscar: The Rose of Versailles [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/RoV_Vol2_Front_CoverArt_V1-480x360.jpg)