(Editor’s note: since this review was written, the official English-language title for the film has been changed to Napping Princess)

Ancien and the Magic Tablet (known in Japanese by the less clunky Hirune Hime, or “Nap Princess”), the latest film from Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex director Kenji Kamiyama, is a veritable grab-bag of current Japanese buzzwords, including the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, robotics and rural revitalization.

Almost all modern films, anime or otherwise, have to feature some degree of product placement and sponsorship to get made, but Ancien feels more like funding looking for a movie than a movie looking for funding.

Maybe I’m just tired of hearing about the 2020 Olympics (everyone who lives in Tokyo is, and the damn thing is still three years away). Or maybe I’m sick of anime set in rural locations in a bald attempt to attract fan “pilgrimages.”

Mostly, though, I guess I’m upset the talents of director Kamiyama were squandered on such an uninspired film. A protege of the arty cyberpunk master Mamoru Oshii, Kamiyama came up through the directorial ranks at Production I.G helming series like Stand Alone Complex, Moribito and Eden of the East. Those series established Kamiyama as a creator of complex, intellectually-stimulating anime, but Ancien feels like something that could’ve been made by anyone.

The film does open with a familiar Kamiyama theme: namely, the existence of a parallel world. While in Ghost in the Shell and Eden of the East, this alternative world exists in cyberspace, in Ancien, it’s the dream world of protagonist Kokone.

Kokone, a high school student who lives in Japan’s rural Seto Inland Sea region with her father Momotaro, is prone to naps, in which she dreams of a kingdom whose residents are all employed by a giant automobile manufacturer (a fantasy version of 1950s Detroit, basically).

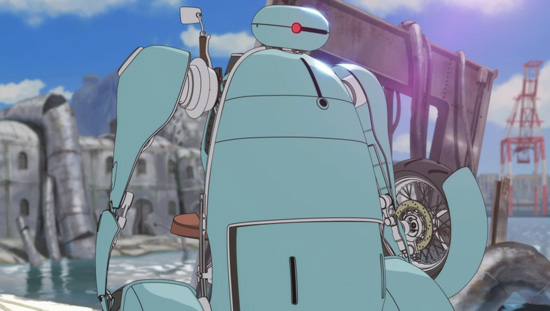

In these dreams, she takes the role of Ancien, the daughter of the kingdom’s ruler, a docile king who is being manipulated by an evil adviser. Ancien works to break the advisor’s grip on her father with the help of a transforming robot named Hearts and a magic tablet that gives her special powers.

The action begins when an agent from Momotaro’s former automobile manufacturer employer appears, demanding the return of a a tablet taken from the company. Kokone slowly begins to realize her dreams, based on bedtime stories told to her by her late mother, might have a connection to her family’s past and the situation at hand.

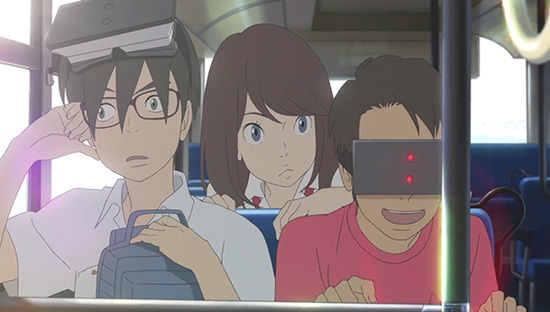

Momotaro is arrested for possessing stolen property, but he manages to get the tablet, which is revealed to contain a secret car-related program, to Kokone, who goes on the run with childhood friend Morio in her father’s motorcycle, taking frequent naps on the way in order to access her dreams and get hints on what to do.

Are Kokone’s dreams simply that, or do they have an influence on reality? For the majority of the film, it seems like the former, but by the end, as the plot of the dream world and that of the real one start to move in parallel, things break down to the point where it’s unclear whether Kamiyama is interested in following his own rules. Films can establish rules as wild and implausible as they like, but once they break them, the trust with the audience is irreparably damaged.

Ancien and the Magic Tablet was animated at SIGNAL.MD, a new subsidiary of Production I.G which is reportedly focused on animation for “children and families.” Ancien is definitely aimed at a younger audience, and it’s possible after mature, adult-oriented series like Stand Alone Complex, I’m simply upset Kamiyama has made something for which I’m not the target audience. But to assume kids will overlook the logical leaps here, I think, underestimates them.

Ancien is, I think, what happens when a film is dashed out to capitalize on current buzzwords: as Kokone travels from location to location, arriving in Tokyo just before the Olympics kick off, it sometimes feels more like an advertisement than a coherent narrative. Add the inconsistent rules of the film’s dream world and I felt like taking a nap of my own.

Matt Schley is Otaku USA’s Japan editor. He doesn’t actually like naps all that much. Find him on Twitter.