Thousands of years ago, three gods working in tandem created the world: Orntorra, the god of the future; Towitorra, the god of the present; and Bantorra, the god of the past. Perhaps the gods grew displeased with their creation, because they disappeared soon afterward. Only Bantorra left behind a legacy in the form of a colossal library.

In this world where magic and technology hold nearly equal influence, whenever a human being dies, he or she leaves behind a stone tablet infused with all of his or her memories and experiences. It is the duty of the Armed Librarians of the Bantorra Library to collect and preserve these “books,” safeguarding the tablets from the unscrupulous people who would abuse the power that the books contain.

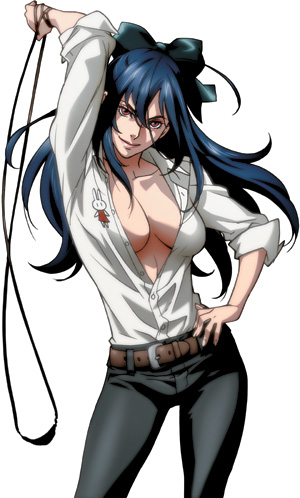

Toward that end, the Armed Librarians have numerous resources at their disposal: they possess ancient artifacts of enormous power, such as the sentient sword Shlamuffen that can parry any attack and a chalice called Argax that can erase peoples’ memories. The Librarians use powerful “magic rights” that grant their wielders superhuman capabilities, such as telepathy, precognition, impossible strength, or the ability to freeze time. They train with firearms. They practice martial arts. And their leader, Hamyuts Meseta, the current Acting Director, is ruthless beyond description, willing to cut down anyone or anything that stands in her way.

Opposing the Armed Librarians is a shadowy religious cult known as the Church of Drowning in God’s Grace. At the bottom of the Church hierarchy are the Meats, pitiful people whose memories and will have been stripped away from them. The Meats are little more than cannon fodder in the war with the Librarians, to the point where they are often transformed through surgery into walking bombs.

Above the Meats are the Mock Men, the middle management who do most of the Church’s dirty work, such as kidnapping children for the Church’s cruel experiments and stealing the books of the dead. Higher still are the True Men, elite individuals whose magical prowess allows them to challenge the best operatives of the Bantorra Library. At the top of the pyramid is the Governor of Paradise, a mysterious figure who manipulates everyone beneath him toward ends that none but he can discern. The goal of the Church is to attain Heaven, although how exactly they intend to accomplish this goal remains a secret.

Finally, there’s Lascall Othello, a renegade being of myth and legend that owes allegiance to neither the Church nor the Library, yet interacts with both from time to time. His mission has something to do with collecting books of great importance. His motives are obscure. Who—or what—exactly is he, and where do his true loyalties reside?

The Book of Bantorra (aka Tatakau Shisho, or “Fighting Librarians,” in the original Japanese) is an anime adapted from a series of light novels by Ishio Yamagata, and it presents a world rich with history, culture, and lore. This setting provides an ample stage for tales of epic adventure, heroism and betrayal, espionage and conspiracy, fragile human beings struggling to forge their own meaning in a realm abandoned by the gods. Sounds straightforward, doesn’t it?

It’s not that simple. Everything I’ve written above about the Bantorra Library, its history, and its enemies is a lie. Unraveling the truth becomes a quest that will test the viewer’s patience.

I’m of two minds about The Book of Bantorra. I admire its moral grayness, its dark heroes, and pessimistic view of humanity. I admire that it tries to tell a mature story through animation, a story that isn’t simply about super-powered “white hats” clashing with super-powered “black hats.” I admire the courage with which the author strikes down important characters, snuffing them out without fanfare and without mercy. The threat of death is ever-present in a manner that is rarely seen outside of the novels of George R.R. Martin. In these ways, The Book of Bantorra reminds me of Giant Robo: The Day the Earth Stood Still, which is arguably one of the best OAVs that Japan has ever produced.

I admire the courage with which the author strikes down important characters, snuffing them out without fanfare and without mercy. The threat of death is ever-present in a manner that is rarely seen outside of the novels of George R.R. Martin. In these ways, The Book of Bantorra reminds me of Giant Robo: The Day the Earth Stood Still, which is arguably one of the best OAVs that Japan has ever produced.

On the other hand, from a narrative standpoint The Book of Bantorra is also guilty at times of both not showing and not telling. It parcels out information with such parsimony that I wonder if series director Toshiya Shinohara simply assumed that the audience had read the novels first.

For example, it’s easy to see that Hamyuts Meseta, the ostensible protagonist, is both a violent psychopath and transparently evil. But although the show provides an explanation for why she is this way—she was raised from childhood to be a weapon capable of slaying a god—it does almost nothing to explore the damaged human being beneath her swaggering, suicidally reckless exterior.

It’s difficult to appreciate the symbolic layers of the show—the meta-textual commentary on the value of writing, the themes about free will versus determinism, the idea of the created defying the will of their creator in a desperate bid for existence—when you have to expend so much mental energy trying to keep the plot straight. What’s a Vend Ruga? Who is the Violet Sinner and why does her alias merit capital letters? What on Earth are “nonentity entrails”? Who the heck is Ruruna Coozancoona, and why am I supposed to be afraid of him again?

Yet despite all of this, I can’t remain peeved at the show. Art isn’t always supposed to be easily digestible, and too often our pop culture entertainment flatters us by serving up everything we want on a silver platter. Some people want nothing more than comfort and affirmation from their entertainment. Some people prefer a challenge, and The Book of Bantorra is a challenging work. It’s the kind of story where the journey is ultimately more important than the

destination.

Although I can’t recommend The Book of Bantorra without reservation because of the issues I have with its narrative structure, I can’t condemn it, either, because it forced me to confront my preconceptions about the nature of storytelling and the value of the human experience. It’s a surprisingly philosophical show that offers no easy answers, only questions that the viewers must seek to define for themselves.

![SSSS.Dynazenon [Anime Review] SSSS.Dynazenon [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/16-9-SSSS.Dynazenon_Key_Visual_3.5-480x360.jpg)

![Back Arrow [Anime Review] Back Arrow [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/ba15-02686-480x360.jpg)

![Dawn of the Witch [Manga Review] Dawn of the Witch [Manga Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/16-9-DawnoftheWitch-cvr_02-480x360.jpg)

![Nina The Starry Bride [Manga Review] Nina The Starry Bride [Manga Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/nina-the-starry-bride-v1-16-9-480x360.jpg)

![Sleepy Princess in the Demon Castle [Anime Review] Sleepy Princess in the Demon Castle [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Maoujou-de-Oyasumi-ED-Large-06-480x360.jpg)