Examining Space Runaway Ideon, another one of Gundam creator Yoshiyuki Tomino’s many beautiful messes.

Anime News Network founder Justin Sevakis once dismissed Yoshiyuki Tomino—creator of the Gundam franchise, Space Runaway Ideon, and dozens of other series both influential and forgotten—as “one of anime’s naked emperors,” a storyteller with a style “muddled and distracted,” lacking for “dramatic timing and emotional gravitas.” If such a declaration sounds callous given Tomino’s distinction within the industry, it’s not necessarily unfair: by any metric modern or classic Tomino is something of a bumbler. His storytelling style is “muddled and distracted,” his “sense of dramatic timing and emotional gravitas” is lacking, every element too often undermined by a reliance on mercurial characters whose attributes shift as the plot demands it and a wishy-washy transcendental metaphysics actively at odds with Tomino’s own graspings after a kind of hard-bitten, hard-boiled realism.

Tomino Effect

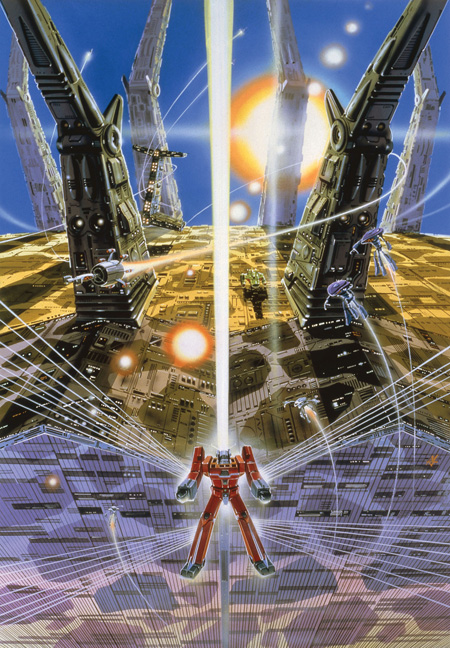

It would be easy to categorize his Space Runaway Ideon as an emblematic mess. The tale of a group of space-faring colonizers forced to flee aimlessly across the galaxy after they earn the ire of militaristic aliens known as the Buff Clan, today it’s known almost exclusively outside Japan as one of the inspirations for Neon Genesis Evangelion. But compared to Evangelion—which with its exacting character studies, iconic psychedelic imagery, and outré approach to shot and scene composition ensures its tale of looming apocalypse feels pressingly of the moment even a quarter of a century later—Ideon seems like it’s been dug up from some Precambrian stratum.

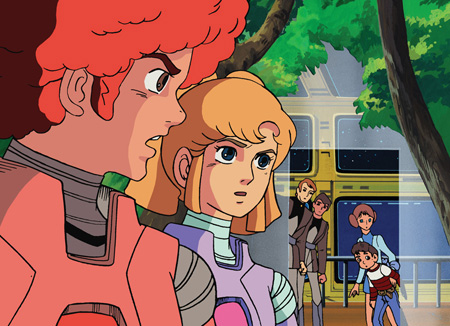

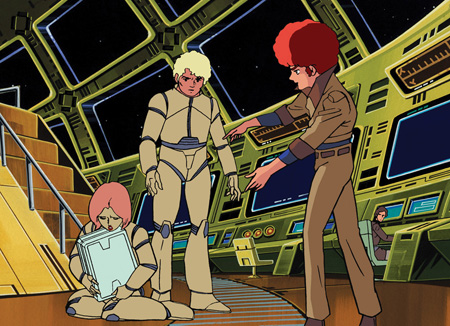

There’s little wonder it took so long to receive an official American release. The structure is so conservative it could generously be described as fossilized: besides a blistering opening two-parter, each episode from the third until the final begins with commander Jordan Bess, Buff Clan defector Karala Ajiba, Ideon co-pilots Cosmo and Kasha and all the rest of the crew of the Solo Ship fleeing across space from the latest robots or strategic gimmicks fielded by their pursuers only to defeat them at the last minute by deploying the titular Ideon. It feels as though Tomino was offended that he ever had to expand the scope of the original Gundam beyond those early episodes where the White Base spent its days running from Zeon and saw Ideon as a way to push that formula to its most maddeningly mundane extreme.

Dramatic developments are sparing; what few do happen—an attempted defection by science officer Sheryl Formosa; an encounter between Jordan and his parents that ends with him court-martialed—lead with only a handful of exceptions not to major advances in plot but to strange moments of character development that don’t constitute an arc so much as the revealing of trivia. Plot development is even less existent, so much so that the series’ climax comes as a surprise, supported by no narrative logic that dictates it ending where it does, no inciting incident that forces the final confrontation between the refugees and the Buff Clan. It feels as if in the absence of a studio mandate Tomino might have dragged the series on for another 39, another hundred, another thousand episodes.

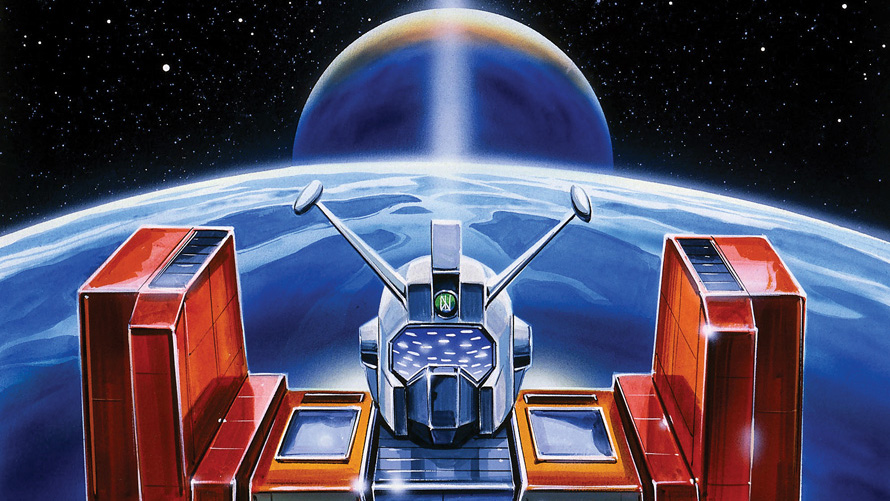

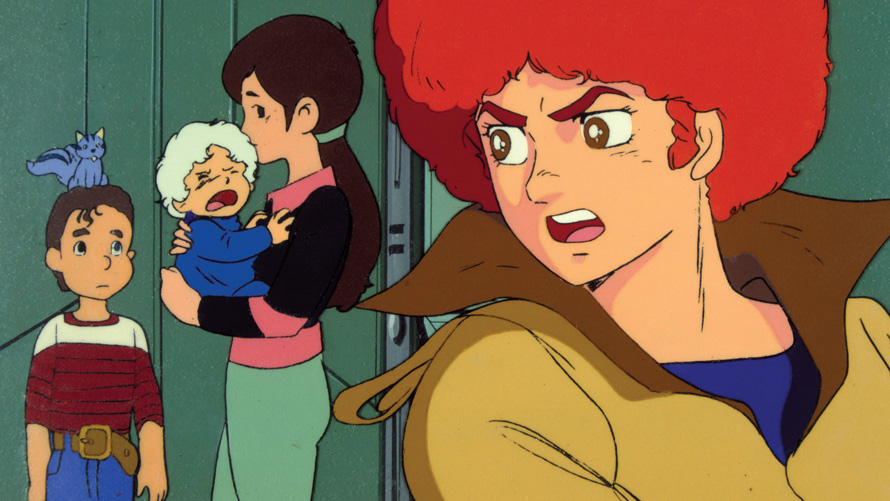

The series’ sense of aesthetics has aged little better: Tomonori Kogaway’s character designs look as if they were cobbled together from the garbage bins of a thousand late-70s sci-fi B-movies and clash heinously with art director Mitsuki Nakamura’s sweeping visions of cosmic vistas (though not quite so badly as the design of the Ideon and its constituent vehicles, which suggests less the slowly waking judgmental god that wiped out countless ancient civilizations than a giant, boxy humanoid fire truck composed of three smaller, somehow even blockier fire trucks).

The series’ sense of aesthetics has aged little better: Tomonori Kogaway’s character designs look as if they were cobbled together from the garbage bins of a thousand late-70s sci-fi B-movies and clash heinously with art director Mitsuki Nakamura’s sweeping visions of cosmic vistas (though not quite so badly as the design of the Ideon and its constituent vehicles, which suggests less the slowly waking judgmental god that wiped out countless ancient civilizations than a giant, boxy humanoid fire truck composed of three smaller, somehow even blockier fire trucks).

While the movie that concludes the series corrects something of these stylistic and narrative deficiencies with a relentless pace and animation and art that remain stunning today, it’s an ending so notorious for its cruelty and pessimism that working toward it can feel pointless. What sense is there in wading through 39 nearly identical episodes to witness the graphic decapitation of children followed by the extinction of all life in the universe? Even the note of redemption it finally offers in a musical montage of the characters’ naked spirits ascending to follow a cherubic child to spiritual rebirth is so bewildering and so contrary to the spirit of everything preceding it that one cannot help but interpret it either as heavy-handed studio meddling or Tomino’s most bizarre, private joke, a flash of irony so blinding we confuse its darkness for light.

Resilient Vision

Yet if it’s not unfair to caution modern audiences away from Ideon in light of these charges it does feel reductionist, because it’s precisely these rough-hewn elements that Tomino, like an alchemist accidentally forging gold from dross by following a vague understanding of already nonsensical pseudoscience, miraculously imbues Ideon with a singular vision of the world that sometimes even resembles genius.

Though after the first handful of episodes that static pacing feels dull—and the prospect of sitting through it for another 30-odd-episodes starts to feel like a prison sentence—after a dozen or so adventures it lends the series a sense of audacity: there must be something hiding in those later stages, something that makes all the struggle worthwhile. But the later stages reveal that there isn’t, though—that this is not a journey but a spiraling toward oblivion—this slogging pace begins to resemble a conscious stylistic decision meant to convey something of what it must feel like to be hounded so relentlessly for so long, to convey something of how hopeless it must feel for the crew of the Solo Ship to wake up each morning to man their stations in anticipation of another inevitable attack that will doubtlessly claim the lives of another few of their slowly dwindling friends, if not their own.

Though after the first handful of episodes that static pacing feels dull—and the prospect of sitting through it for another 30-odd-episodes starts to feel like a prison sentence—after a dozen or so adventures it lends the series a sense of audacity: there must be something hiding in those later stages, something that makes all the struggle worthwhile. But the later stages reveal that there isn’t, though—that this is not a journey but a spiraling toward oblivion—this slogging pace begins to resemble a conscious stylistic decision meant to convey something of what it must feel like to be hounded so relentlessly for so long, to convey something of how hopeless it must feel for the crew of the Solo Ship to wake up each morning to man their stations in anticipation of another inevitable attack that will doubtlessly claim the lives of another few of their slowly dwindling friends, if not their own.

This mounting sense of dread plays well with the series’ murky explanations behind the energy source known as the Ide from which the Ideon and Solo Ship derive their power. No simple metaphor for the infinite destructive potential of nuclear power like the Getter Energy of Go Nagai’s Getter Robo, no, the Ide is rather some kind of universal malignant will of incomprehensible origins and intentions that operates by principles the crew that depends upon it cannot understand. Some hints imply that the civilization that left behind the Ideon are now in control of the Ide, while others posit them as just one more victim in a long line of such civilizations doomed by a malign will beyond human reasoning with no clear answer ever provided.

The mechanics by which it operates remain abstruse even after they have wiped out the universe. The only thing that’s certain is it resonates deeply with the will of children and abhors human conflict, yet we are also told it has engineered the endless escalation of conflict between refugees and Buff Clan by bombarding both civilizations’ home planets with meteors. In any other story or even in the early episodes of Ideon these ambiguous mechanics can feel like an author’s clumsy attempts to add tension to the battles and mystery to the mythos. But as events plod along that same capriciousness begins to feel less like authorial indecision than the incomprehensible puppeteering of some eldritch entity interested in Cosmos, Kasha and all the rest of the Ideon’s pilots for ends they cannot hope to explain.

Infinite Inevitability

There’s an element of horror at play in Ideon that’s too often understated in discussion, but not the horror of jump scares or even the psychological nightmares that plague the cast of Evangelion. Its horrors aren’t even quite the same as those horrors of war that Tomino was showcasing in Gundam despite how much ado is made here as there about man’s endless appetite for conflict. Rather, the dread creeping throughout Ideon is of an existential terror that mortality is a noose tightening by millimeters around the neck day after day, pulled by the hand of an alien executioner you cannot reason with or understand. That life and will are somehow abhorrent to the natural universe.

This in turn lends an uncanny weight to the often directionless sense of character development and even lends pathos to some of the more bizarre character-writing choices Tomino makes. These are people forced into a senseless conflict with senseless stakes according to a senseless operating principle. It follows that their behavior would play erratically to an outsider observer. Somehow the final result is a series of uncanny effect that concludes with one of the most powerful endings in the medium’s history. There is absolutely nothing like it, most likely for good reason, and yet there is such a deep sense of loss and a desperate longing in the last sequence of souls headed toward rebirth that one can feel Tomino’s desire for salvation and redemption in the face of all logic to the contrary that it cannot help but elicit sympathy for these characters and their creator. No grim irony, it reads like the most aching longing for deliverance imaginable only all the more so because everything that preceded it precludes its possibility.

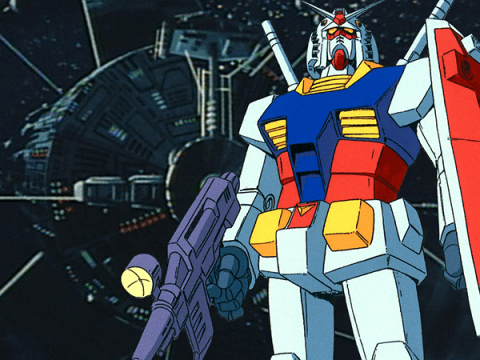

To describe these stylistic decisions as deliberate would seem misleading given how awkwardly they’re handled throughout; a more competent writer could more easily signpost these themes, might develop them more evenly, might have more organically highlighted the growing sense of dread and the alien behavior of the cast. Moreover, these tics smudge everything Tomino touches like an oily thumbprint: 40 years on it remains difficult to reconcile the man’s declaration that Gundam was the first “real robot” series with the fact that the resolution of its central conflict involved space psychics coming together in an operatic display of neon green lights to turn away a meteor plummeting toward Earth. As an artist he has always been guided purely by instinct and feeling. Too earnest to make the calculations of style and technique so many other creators labor over, he approaches his stories—and us—from angles that few others would ever imagine because they are so obviously roundabout or clumsy that they inherently entail a plethora of failures, from nonsensical character writing to labored pacing to didactic moralizing to bombastic spectacle so tonally contrary to all that’s come before they often play as a twisted joke when they aren’t simply bathetic.

To describe these stylistic decisions as deliberate would seem misleading given how awkwardly they’re handled throughout; a more competent writer could more easily signpost these themes, might develop them more evenly, might have more organically highlighted the growing sense of dread and the alien behavior of the cast. Moreover, these tics smudge everything Tomino touches like an oily thumbprint: 40 years on it remains difficult to reconcile the man’s declaration that Gundam was the first “real robot” series with the fact that the resolution of its central conflict involved space psychics coming together in an operatic display of neon green lights to turn away a meteor plummeting toward Earth. As an artist he has always been guided purely by instinct and feeling. Too earnest to make the calculations of style and technique so many other creators labor over, he approaches his stories—and us—from angles that few others would ever imagine because they are so obviously roundabout or clumsy that they inherently entail a plethora of failures, from nonsensical character writing to labored pacing to didactic moralizing to bombastic spectacle so tonally contrary to all that’s come before they often play as a twisted joke when they aren’t simply bathetic.

Yet by approaching art from these idiosyncratic angles he affords us an encounter with unfamiliar aspects of familiar emotions that others have shied away from. Naked emperor Tomino may be, but in that nakedness he exposes something of the absurdity of our human experience that all the finery and regalia of other authorities exists only to hide or carefully accentuate.

Space Runaway Ideon is now available to stream on HIDIVE and in a complete Blu-ray collection from Maiden Japan.

![SSSS.Dynazenon [Anime Review] SSSS.Dynazenon [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/16-9-SSSS.Dynazenon_Key_Visual_3.5-480x360.jpg)

![Back Arrow [Anime Review] Back Arrow [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/ba15-02686-480x360.jpg)