The roundtable listens intently to Consul-General Tadahiko Yamaguchi’s speech

Last month in Denver, Colorado, academics, industry leaders and fans alike met up for SANA, the Summit for Anime in North America, an event organized to ponder just why anime has the appeal it does in the States. Part one ended with the story of the ongoing success of the Robotech franchise, which was essential in introducing a generation to anime.

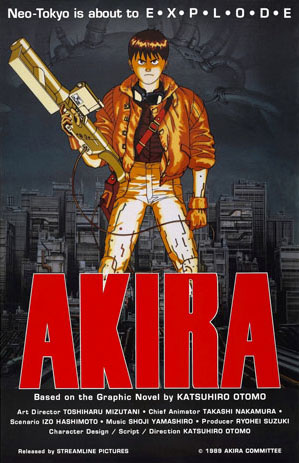

Fittingly, then, the next presentation was “Introducing Anime in the U.S.”, courtesy of Streamline Pictures co-founder Jerry Beck, former business partner of Robotech producer Carl Macek. Part personal history, part industry history, Beck outlined how he went from working as a salesman for United Artists in the late 1970s to working with the late Macek to form Streamline Pictures in 1989, eventually releasing anime movie classics like Akira and Castle of Cagliostro in the United States and exposing an entire generation of western anime fans to their first loves. Along the way, he had chance meetings with manga god Osamu Tezuka in the early 1980s, and helped run the Los Angeles Animation Celebration festivals in 1987 and 1989.

Poster for Akira with memorable tagline

courtesy anime pioneer Jerry Beck

Beck also shared some Streamline Pictures trivia, like how he was the one who coined the infamous tagline “Neo Tokyo is about to E.X.P.L.O.D.E” for Streamline’s Akira film poster, and how the reason he left the company in the ‘90s was because he had “checked off all the movies [he and Carl] had wanted to release from our list.”

Concluding the event was a Q&A session intended to address the summit’s core question: “Why is anime so popular in North America?” To kick things off, Deputy Consul-General Tadahiko Yamaguchi gave a rousing speech on how he hoped those back home in Japan will think about how they communicate with other nations, while also hoping fans of Japanese pop-culture will deepen their understanding and appreciation of Japanese culture in general, all while emphasizing the importance of trust between America and Japan.

So, then. Why is anime so popular in North America?

Jerry Beck’s answer was anime’s “outlaw” sensibility, particularly in the early days of the American industry. “These weren’t the cartoons your mom watched as a kid. There’s definitely a certain appeal to that.”

Beck also pointed out that there was a 30 year gap between The Flintstones and The Simpsons, during which time very few people were attempting to do anything deep or emotionally engaging with animation in the United States. Anime filled a void, satisfied an audience that was desperate for a certain kind of content.

Dr. Ian Condry agreed. “Anime filled a space that was missing for a long time: animation for teens and adults.”

Of course, he also addressed one of the core problems facing the modern American industry when he mentioned that the president of MIT’s anime club once referred to the importance of a “proselytization commons” as a means of spreading anime’s popularity – a fancy term for piracy.

There wasn’t much follow-up on that topic beyond the usual pleas to fight piracy, but the panel did agree that the 1954 senate subcommittee hearings on comic books killed entirely the possibility that America would have a vibrant comics or animation subculture in the same way Japan did during the same time period.

Poster for Akira with memorable tagline

courtesy anime pioneer Jerry Beck

Kevin McKeever suggested the reason Robotech caught on so well was because “it was a cartoon that respected its audience.” Several members of the audience – including an original member of Denver’s branch of the Cartoon Fantasy Organization – agreed.

“I remember watching Scooby Doo as a kid, and it was just Scooby messing up for 30 minutes. Anime was a breath of fresh air.”

Another member of the audience cited her experience watching Studio Ghibli films with her daughters as evidence of anime’s lasting power as an entertainment medium capable of crossing boundaries of language and culture.

“My daughters love Totoro, but it’s not because it’s from Japan. It’s because they connect with the characters.”

Sarah Sullivan capped the discussion by emphasizing the strength of the American fan community, and its willingness to accept anyone. The overwhelmingly positive response from American anime fandom after the earthquake and tsunami in Japan on March 11, 2011 struck a bold contrast to where things were only 30 years ago, McKeever said.

“We’ve come a long way from the anti-Japan days of the 1980s, and anime has absolutely played a huge part in that.”

![Doc Big in Japan Offers A Guide on How (or How Not) to Get Famous in Japan [Review] Doc Big in Japan Offers A Guide on How (or How Not) to Get Famous in Japan [Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/biginjapan01-480x360.jpg)