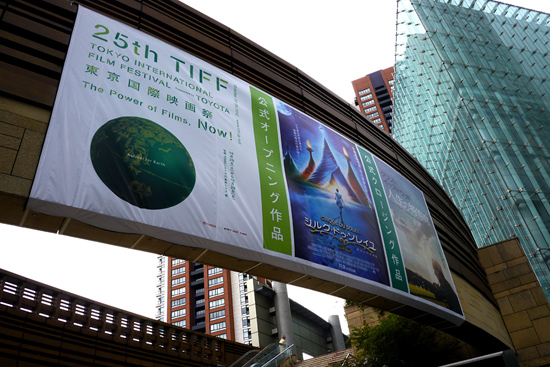

For the past 25 years, filmmakers, reporters, critics and film fanatics in Tokyo have been setting aside a week in late October for the Tokyo International Film Festival, Japan’s biggest cinematic event. Though not quite as significant as festivals like Cannes or Sundance, Tokyo nonetheless draws hundreds of films, thousands of filmgoers and some serious industry heavy-hitters both from within Japan and abroad.

The 25th TIFF, which was held in the Roppongi Hills building complex in the middle of Tokyo, was no exception, hosting films from around the world and boasting a jury chaired by legendary director and producer Roger Corman (your Otaku USA, spotting Corman in the cinema bar, got seriously star-struck).

Naturally, we concentrated on Japanese films, specifically the category TIFF calls “Japanese Eyes,” which is mostly comprised of films from young, often first-time directors.

Even within a subsection of a huge festival like TIFF, it’s hard to get a read on the overall mood, but if there was one common thread throughout the films we saw, it was last year’s so-called triple disaster: the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown in northern Japan. While last year saw the release of many documentaries on the subject, this year narrative films, which generally have a longer incubation period, caught up and dealt with the disaster in their own way.

Something Wicked Comes Over the Wall was once such film. Directed by sophomore director Norio Enomoto, Something Wicked begins innocently enough, with a syrupy-sweet ukulele-based three piece band making their way to a gig in their beat-up van. The mood slowly turns as the band discusses rumors the venue to which they’re headed is filled with ghosts.

Finally, the van breaks down in the middle of the night and the trio are forced to spend the night in total darkness. Waking up, they realize they’re stopped at the edge of the horrible destruction wrought by the tsunami. The ghosts they’ve been discussing aren’t some old horror stories: they’re the very real and very recent memories of death in the north.

The film, which is only 35 minutes, nevertheless manages its descent from sweetness to somberness well, and its characters are fairly fleshed-out and sympathetic. The runtime, plus shaky digicam camera work makes Something Wicked feel somewhat amateurish, but the unflinching footage of the destruction, taken on location, delivers a real gut punch.

Since Then, another film dealing with the disaster (and featured on a double bill with Something Wicked), shows how radically different two films about the same subject can be.

The film, directed by longtime filmmaker Makoto Shinozaki and crewed by students at the Tokyo Film School, deals with the effect of the earthquake on Tokyo, which, while undamaged in comparison to the north, was nonetheless dealt a huge psychological blow during and in the aftermath of the quake.

Since Then concerns a woman who owns a shoe store in the suburbs of Tokyo. On the day of the quake, she tries desperately to reach her boyfriend, who we learn lives close to the disaster-struck area. Unable to get through because of poor phone service, she frets for days, constantly checking her phone.

She’s eventually reconnects with her boyfriend who, it turns out, is mentally unstable. Though he had been recovering, the disaster has shaken him up, and the woman must decide whether it’s worth staying with him after he takes a turn for the worse.

The greatest success of Since Then is capturing the mood in Tokyo right after the quake. It portrays a city in which the people, though internally deeply shaken, have nothing to do but to externally go about their business. Though Tokyo remains largely unaffected, constant aftershocks are a reminder of what’s happened and each brings a pang of survivor’s guilt.

The film’s cinematography and pacing, both delicate and deliberate, perfectly reflect both the mood of Tokyo in general and that of the main character, who can do nothing but wait. The only major flaw in Since Then may be length: at about an hour, it’s too long to feel like a short film, but too short to stand on its own.

Where Does Love Go? is another film that deals with the earthquake, if in a roundabout way. Based on a true story, it deals with one of the last remaining fugitives of the sarin poison attacks on the Tokyo subway system in the mid-nineties. The fugitive, on the run with his girlfriend since the attacks, finally decides to turn himself in after the quake serves as a catalyst to change his perspective.

The film takes place the day before he goes to the police, and considers what the final conversation between he and his girlfriend might have been like. Based on a play, it largely takes place in one room and has only two characters. This serves as an advantage, though, in portraying the mundane life of a fugitive, who, after all, has no choice but to sit inside all day for fear of being spotted.

The cinematography, stark black and white, helps enhance this theme: his existence is so drab it lacks any kind of color. Finally, the conversation between the two characters, so domestic and pedestrian, cements the idea that being a real life fugitive is less Harrison Ford being chased by Tommy Lee Jones and more, well, sitting around.

Unrelated to the triple disaster but definitely about modern Japanese life is GFP Bunny, which won Best Picture in the Japanese Eyes section. Directed by Yutaka Tsuchiya, whose experimental film Peep “TV” Show was released a decade ago in the West, strikes back with another strange blend of narrative and documentary, this time using a real-life incident, in which a teenager attempted to poison her mother with thallium, as a springboard to explore how science and technology are changing human life.

The girl in GFP Bunny, much like the real-life Japanese girl, slowly poisons her mother, but here, her motivation seems to be as a kind of science project: she’s obsessed with modifying the human body though genetic manipulation. As the film unravels, it makes the case that genetics and computer code are two sides of the same coin: after all, at their respective cores, computers are just 1s and 0s, while humans are just the A, T, C and G of DNA.

The film makes its case by stringing together wildly different forms: the main narrative, plus documentary interviews with scientists, YouTube clips, camera phones, and even behind-the-scenes footage from the very film we’re watching. This is some meta stuff, man. Not for the faint of heart, but very compelling, GFP Bunny is a fascinating exploration of our modern condition.

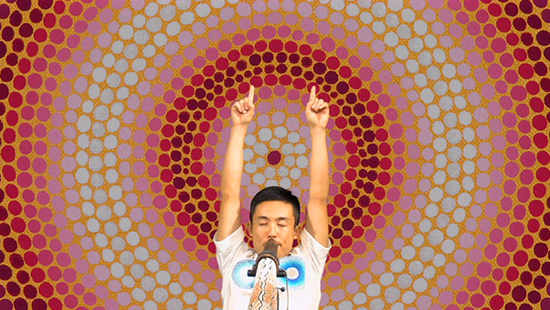

Finally, we ventured outside the Japanese Eyes category and into that of the main competition, where we saw Flashback Memories, the eventual winner of the Audience Award. Flashback Memories was directed by documentarian Tetsuaki Matsue, who has a reputation for using interesting techniques: his 2009 film Live Tape was shot entirely in one take.

In his new documentary/concert film Flashback Memories, Matsue uses 3D to portray the life of Goma, a Japanese musician who plays the didgeridoo. After a decade of honing his skill, playing events and winning awards in Japan and throughout the world, Goma was involved in a traffic accident that left him unable to create new memories and live life in a kind of daze. His muscle memory remained intact, however, and Matsue aimed his 3D cameras at a recent live performance in which it was clear Goma has lost none of his musical talent.

I’m a 3D skeptic, but it works well here. Goma and his band kind of float above past footage, taken from over ten years of archival video camera footage and still photographs that show the progression of Goma’s musical career.

Where there’s no footage available, like in the case of Goma’s traffic accident or his state of mind afterward, Matsue uses beautiful, abstract animation based on Goma’s own paintings, which he began painting after his accident.

Interesting filmmaking techniques aside, the film has real substance: it’s the tale of an artist who’s suffered a major setback and his family, who support him throughout. Through the years of assembled footage, we see Goma get engaged, married and have a daughter, who grows up in front of our eyes. His wife and daughter play the central role in his recovery, and Matsue makes the case that with the help of both his music and his family, Goma might just make it.

The final film we saw at TIFF was a South Korean movie called Sleepless Night. It’s a bit outside of our wheelhouse here, so I’ll just mention two things: one, it was quite excellent, and two: despite recent tensions between Japan and its neighbors China and South Korea, the house was packed with Japanese filmgoers who applauded the film and praised the director, who was in attendance, after the screening. It was a nice reminder that most people can ignore the bluster of politicians and connect as humans over a good movie.