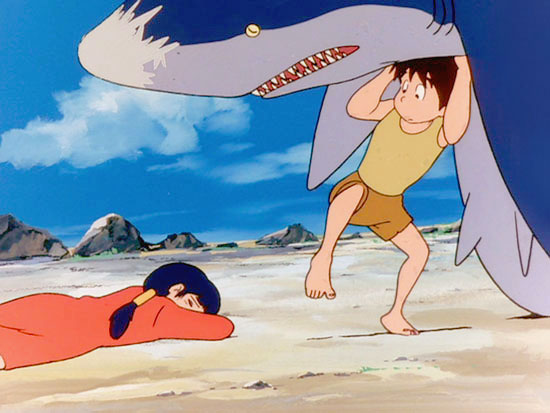

An old man sits writing in his home, built from the ruins of a crashed space rocket. He is interrupted by a young boy, who shouts excitedly that a shark is attacking the fish, before snatching a spear and running off. He climbs over the rusted hulk of an old battleship, takes a deep breath and dives in.

Underwater, fish swim among the remains of a city, crashed cars piled up against the rotting shells of what used to be homes and offices. A shadow falls over the boy. The shark has found him. The boy is unperturbed.

How long do you give it? This is the question for anime fans as they digest a new series and decide if it’s worth persevering with. It’s a thorny one, with fans at one extreme insisting that you need to watch perhaps a dozen episodes before making a judgment, and those at the other countering that only three episodes is sufficient.

Both sides are wrong though, because as the opening to episode one of Hayao Miyazaki’s Future Boy Conan above shows, a good writer and director only need a few seconds to grab your attention. That sequence lasts about seventy seconds and tells us so much. We can see from the city that the world we know has gone, the rocket tells us that escape attempts failed, and the battleship tells us that the end was probably a fiery one. We know that Conan is fearless, that he has a tendency to jump into situations without much thought or forward planning, and we know he has a strong, instinctive urge to protect. Right from the start, we know our hero, we know his world, and he has been placed in peril. We’re rooting for him, and we need to know how it turns out.

Those familiar with the series will at this point be screaming that no, in fact this sequence is not the intro: Future Boy Conan actually begins with a montage detailing the world’s destruction, followed by an expository voiceover by the old man. This is true, and it’s a weakness, because the adventure with the shark easily and visually gives us all that information anyway. Voiceovers are a gift to lazy writers, and they are a difficult tool to use well.

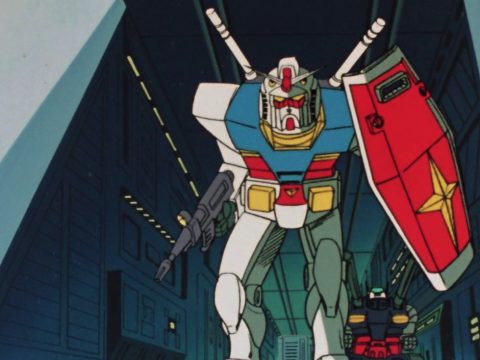

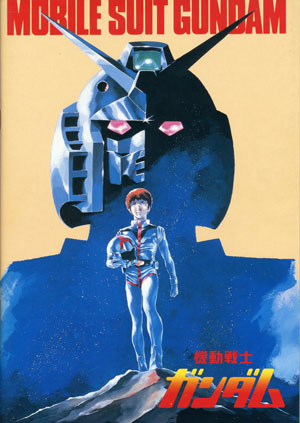

In the original 1979 series of Mobile Suit Gundam, the voiceover intro is unavoidable because of the need to impart specific information on the political background. We see the space colonies, we see the battle fleets in combat, we learn of the terrible human cost of the war, and it closes with the apocalyptic pink glow of the infamous Zeon colony drop. It then cuts to the action and again it’s a very effective piece of writing.

In the original 1979 series of Mobile Suit Gundam, the voiceover intro is unavoidable because of the need to impart specific information on the political background. We see the space colonies, we see the battle fleets in combat, we learn of the terrible human cost of the war, and it closes with the apocalyptic pink glow of the infamous Zeon colony drop. It then cuts to the action and again it’s a very effective piece of writing.

The camera pans across open space and we see three mobile suits. They land on the exterior of a giant space colony. Two of them make their way through the airlock, a man emerges from his suit and begins scanning the colony with a pair of binoculars. They seem to be planning an attack on a military facility. The area seems to be deserted, but then he spots a small girl. Unknowing, the girl runs inside her house, calling the name “Amuro!”

This sequence lasts about two minutes, and it does two very important things. It moves us from the vast events of the opening montage down to the grunts who do the day-to-day fighting, down to the lives of the civilians caught up in the war. It tells us that Mobile Suit Gundam is a story concerned with the little things as well as galaxy-spanning military heroics, and it tells us that this is a human conflict and that the story is interested in both sides.

The other thing it does is immediately put something at stake. We now know that someone is watching the little girl, that something is going to happen, and she has been put in the line of fire. We want her to be OK.

Distorted sounds of traffic as the camera cuts between shots of Tokyo at night. A pedestrian crossing, the neon lights of shops and game centres, streets crowded with people, the sky crisscrossed by a web of electrical wires. “Why won’t you come here?” a girl’s voice asks.

A sleazy looking backstreet, couples walking along, a schoolgirl seems to be having a panic attack in an alleyway. Some girls giggle at her. Cut to text against a digital pattern backdrop. It reads “Why should you do that?”

A tanned girl with dyed hair fends off the attentions of a drunk businessman. The schoolgirl takes off her glasses and smiles. Her hair falls free, she leans off the edge of a building, holding her glasses aloft like a superhero striking a pose. Her lips move but no sound comes out. Cut to text: “I… don’t need to stay in a place like this.”

She drops. The businessman and the girl are now kissing. There is a crash and the couple turn to stare in astonishment.

The opening of 1998 sci-fi mystery series Serial Experiments Lain delights in disorientating the viewer from multiple angles, but it works its subtle magic in a way few shows have bettered.

The locations would be familiar to anyone living in a decent sized Japanese city, but the sound design and visuals are deliberately unsettling. This is our world, but there is something not quite real about it. The way the girl’s lips move but her words only appear as text on a digital backdrop foreshadows the show’s theme of the interpenetration of digital and physical domains. Her behaviour is unusual for a suicide. She seems to be acting in the grip of a kind of madness, and her actions are presented as a symbolic act of breaking free.

The girl falls from the building and within two and a half minutes of the show’s opening, we have a body, a mystery, and the lingering touch of the supernatural.

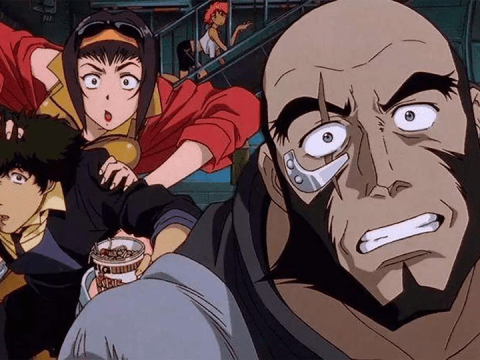

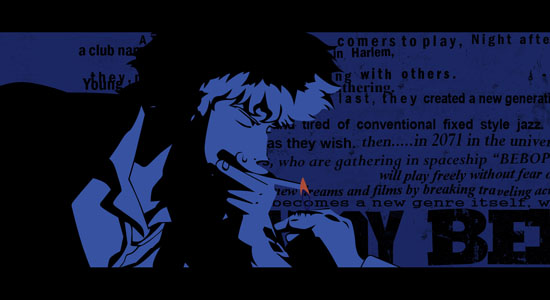

A church bell rings, rain falls. A music box melody plays as a man drops and crushes out his burned-out cigarette. He carries a bunch of flowers as he moves off. A single rose drops into a puddle. The camera lingers on the rose as we intercut with bullets spraying from a gun concealed among the roses, more gunfire, blood-soaked fingers play with a detonator switch. The melody stops, blood runs down the man’s face like tears, a flash of colour, and the trumpets start.

It only takes forty-eight seconds for sci-fi adventure series Cowboy Bebop to get its hooks into the viewer. What can we take away from it? We know the character is a man with a violent, probably criminal past. We know he’s also a sentimental man. We suspect there is a woman involved.

The transition is also important. More than perhaps any anime series ever made, the opening credits sequence of Cowboy Bebop plays a crucial role in setting the tone of the show and preparing the viewer for what’s to come. After that rather dark, melancholy pre-credits sequence, the way the show suddenly changes tempo and slaps you hard in the face with jazz completes the picture. Strap on your seatbelts, because this show is going to be fun, fun, fun, but there’s a thread of darkness, violence and loneliness running through it.

In recent years, it seems like these sharp, intelligently written, visual openings have been dying out. The reason why is open to speculation. The declining relative importance of manga as source material as visual novels and light novels, with their emphasis on words rather than images as the key storytelling device might be part of it, and certainly might explain the overuse of unnecessary voiceovers in shows like romantic drama Clannad and tediously talky supernatural adventure series Shakugan no Shana.

It also seems that audience expectations have changed. Until the late 90s, most TV anime was written more or less along what you might call Hollywood lines. It worked on the assumption of a basically mainstream audience, who were looking for a gripping narrative and relatable characters. As otaku fans became a more financially important audience for shows, and as more otaku gained development roles in anime studios, there seems to have been a shift in anime scriptwriting’s orientation towards tropes and types rather than traditional stories and characters. Anime became a pick & mix of standard elements, with audiences extracting pleasure from the subtle variations, unfamiliar combinations, and subversions of those elements.

In this situation, a successful intro is one that would to a mainstream viewer seem like nothing more than a succession of clichés, but is actually delivering the key elements to the otaku audience, ready to be toyed with as the series progresses. The role of the first few seconds has been reversed, and there is an embedded expectation that the audience will give the series several episodes to see how these clichés or standard elements will play out.

A girl is running though a labyrinthine chessboard world. The camera focuses on the crucial zone between the rims of her stockings and the hemline of her skirt. She is breathing heavily. She sees a sign for the exit, a rather incongruously ordinary sign in such a bizarre world. She goes through the door…

A girl is running though a labyrinthine chessboard world. The camera focuses on the crucial zone between the rims of her stockings and the hemline of her skirt. She is breathing heavily. She sees a sign for the exit, a rather incongruously ordinary sign in such a bizarre world. She goes through the door…

…Into a nightmare of dark clouds and jagged, black branches. Another girl is fighting against an unknown, unseen foe. She is losing badly. A small, white catlike creature speaks, its mouth not moving. It says that the girl can help her friend if she chooses, that she can change her destiny if she enters into a contract.

The opening to Puella Magi Madoka Magica is an interesting one in that it satisfies on both counts. The scenario of the magical girl show with the cute mascot character is familiar, although the way the creature appears to be blackmailing the girl into taking the deal instantly subverts the format by casting the mascot in a Mephistophelean role and injecting a Faustian element into the drama.

It also satisfies on a more traditional dramatic level, by beginning at a moment of extreme peril, with the stakes at their highest. The use of a flash-forward is a bit of a cheat (although the importance of that scene as the pivot on which the series turns becomes apparent later), but it serves to add tension to all the subsequent scenes. Madoka’s mundane daily life and interactions with her friends and family are now coloured by the foreboding that the intro has instilled in us. The appearance of Kyubey is freighted with meaning as we already know he is capable of at the very least rather manipulative behaviour. The seeds of a mystery are also planted: What is the contract? What is the cost? Who is the girl’s friend fighting? What is Kyubey’s agenda?

In the cut and thrust of fan discussions, the line that “You haven’t watched enough of it to judge,” is an easy way to invalidate someone’s argument, and we certainly shouldn’t let some moments of poor writing blind us to greater enjoyment to be had elsewhere in a show, but people should pause to ask themselves why that investment of time should be necessary. A twelve-episode show with a boring first three episodes is 25% a failure, and the patience that fans have with even the most poorly-written shows allows directors and writers to get away with the most appalling laziness. While a show that starts out poorly may indeed blossom into something magnificent after seven episodes, why shouldn’t we expect that attention to detail from the start?

This story originally ran in the 4/30/13 issue of the Otaku USA e-News

e-mail newsletter. If you’re not on the mailing list, then you’re reading it late!

Click here to join.