I’m standing in the sweltering heat at Otakon 20, but my mind keeps wandering back to Otakon 13. I was 19 years old, bewildered, and attending the first convention of my life.

Do you remember your earliest anime convention? If you’re in your ‘20s, it was a time before Homestuck, when in fact people still looked down at people for cosplaying characters from video games, because “this is an ANIME con!” You discovered for the first time that lots of people liked the same shows as you, even though in your hometown you were a curious exception to the rule of normalcy. You ate like crap and slept eight to a room because it’s what you could afford. You actually went to the video rooms, because they showed anime you couldn’t otherwise watch without waiting two weeks for your Napster downloads to finish.

Newer fans may have missed it, but the nostalgia hit me harder than the tang of sweat and melting body paint in the stifling Baltimore summer. For me, Otakon 20 was a time machine to my earliest fandom memories. As I stood on a wildly different conscape than the one I first saw seven years ago, I couldn’t help comparing it to the past.

Twenty years of Otakon

Even after 20 years, Otakon is firmly rooted to its origins. The most visible example is that Otakon 20 began and ended with a showing of Otaku no Video, the founders’ original inspiration for Otakon’s mission and name. Never mind that the room barely even reached half capacity. The nostalgia must be felt.

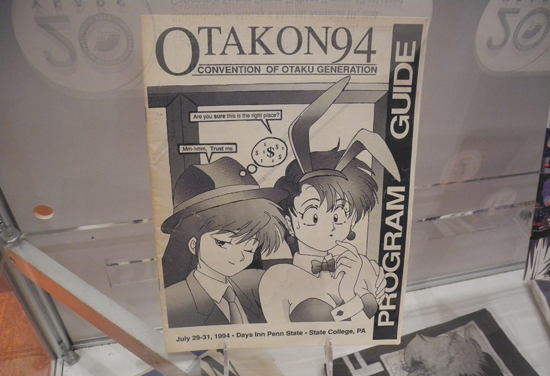

In the Otakon Museum, a new attraction built especially for the anniversary, Otakon’s black-and-white Xeroxed pamphlet from ‘94 sits in a glass case opposite this year’s glossy, color keepsake. Convention badges are displayed like relics. It’s a tribute to the ritual of Otakon, a pilgrimage some fans have been making for up to 20 years now. Situated inside the aging convention, it’s like a time capsule within a time capsule.

On Saturday, 12 of Otakon’s previous convention chairs presented “By Fans, For Fans: 20 Years of Holding On For Dear Life,” narrowing in on the convention’s transformation.

We heard the story of how Otakon went from a 300-person gathering in sleepy State College, Pennsylvania, to a 35,000-attendee mega-event in the Baltimore metropolis.

For an hour, the con-runners shared their memories of Otakon’s most bombastic successes and disasters. There was the “Dealer’s Closet,” consisting of the 2½ dealers they managed to secure in ‘94. There was the 2008 animation Otakon co-produced with high profile anime studio Madhouse. There was 2001, the year an underground toxic waste spill caused manholes around the convention center to shoot into the sky.

But most interesting were the founders’ recollections of anime culture in the Before Times. Stories of reading along to an English script while watching anime on tape in its original Japanese. Chatting about Macross on Usenet. Formulating Otakon on the ride home from Chibicon, a subset of I-Con and the closest fan convention to the east coast that existed at the time.

“There weren’t any anime cons on the east coast,” a founder explained. “In fact, the U.S. just had A-Kon, Anime Expo, and Animerica.”

Today Otakon is a dot in a vast landscape of anime conventions that can be found in every state and major city. But while other cons pop up like mushrooms, only to eventually wither and fade, Otakon is still going strong. That’s because it’s not the same Otakon I remember from seven years ago—and here’s why that’s a good thing.

Why Otakon had to evolve or die

“How many people in the audience count themselves as part of one or more fandom?”

That was the first question posed by Charles Dunbar, a panelist at Friday’s “We Con, Therefore We Are: Fandom, Convergence and a Critical Look at the Modern Otaku.” Nearly every hand in the auditorium shot up.

“And how many people consider anime to be their primary fandom?” he continued.

Most of the raised hands dropped.

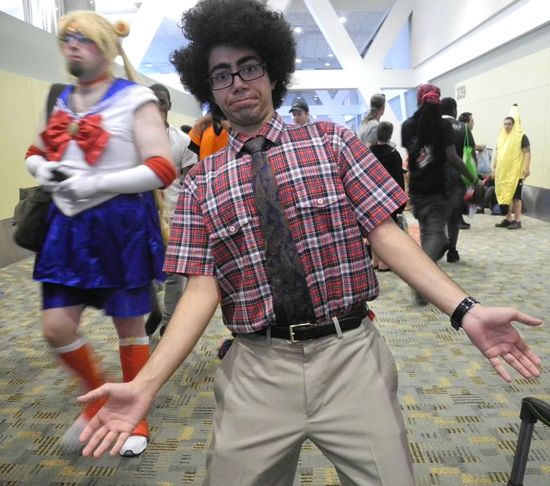

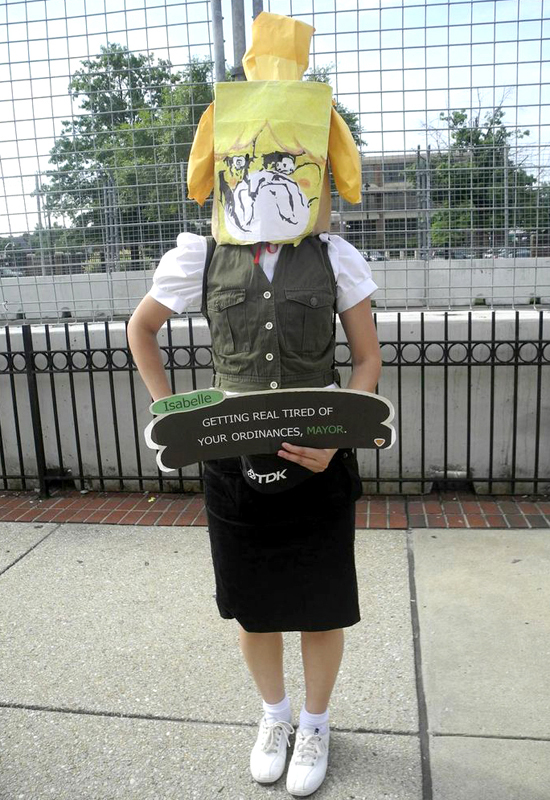

Based on the weekend’s cosplay, it’s no surprise to anyone with eyes that western shows like Avatar and Sherlock, plus the ever-popular Homestuck and My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, are now the dominant fandoms of Otakon. As anime fandom has burrowed further online, mainstream geek fare like The Avengers has become increasingly accessible and welcoming to new fans.

Dunbar quoted Evan Minto’s article on Homestuck’s waxing fandom and anime’s waning one. While other fandoms make evangelism (for example, the calling card phrase “Let me tell you about Homestuck,”) an integral part of their mission, anime fans don’t. As a result, Homestuck grows and anime fails to attract newer fans.

Perhaps Otakon has also seen the writing on the wall. Its mission is limited to “East Asian culture,” but, according to Con Chair Terry Chu, Homestuck and bronies are more than welcome to try and wedge their way into the Otakon wheelhouse.

“When a panelist has a good tie-in to our mission, like the way Homestuck is similar to Japanese mythology or something, then yes, we’ll accept them,” he said.

Dunbar would have agreed. “If what fans want doesn’t exist, they will create it,” he said.

Fandom is converging, and conventions can either adjust to it or fade away.

What’s in store for Otakon 40?

New stuff is coming out all the time, but Otakon continues to evoke a timeless mood. The game room still offers ‘80s classics, as does the manga library. The AMVs and fan parodies still harken back to the greatest hits, like Fullmetal Alchemist, Death Note, and even Sailor Moon. Forget the Otakon Museum; Otakon’s history is alive and well here.

Little has changed in some of that programming since I was 19. It’s no wonder that some fans reject the official events, organizing hundreds of their own gatherings instead. In a time when fans can get their media online, Otakon stays relevant as an established gathering point for geeks to connect and socialize.

At age 20, Otakon is stuck between a past most of its attendees don’t remember, and a future that has wildly diverged from its original mission. Nostalgia isn’t going to resonate with attendees for much longer.

In the future, Otakon could go one of two ways. It could focus inward, forcing other fandoms to branch off and create their own cons, the way BronyCon did. Or it could expand its scope to more fandoms, exploding its attendance more and more each year. Under Chu’s leadership, the second option seems likely.

“The culture of conventions is one of inclusion and acceptance,” said Chu. “We’re all equally passionate about the things we love, so we should be equally accepting, too.”

But I have no doubt that they’ll still be opening the con with Otaku No Video in 2033.