With glimpses into Japanese subculture mostly supplied by the likes of Genshiken and the future of Japan given pessimistic overtones in Eden of the East—not to mention the countless headlines in the news at home and abroad of Japan’s shrinking birthrate, debt-ridden economy and seemingly apathetic youth—finding the embers in the ashes is Morinosuke Kawaguchi. Working at the Arthur D. Little management consulting firm and as lecturer at Tokyo Institute of Technology, he seems like the most unlikely candidate to be rooting for the triumph of the geeks. Such was the thrust of a lecture given recently at the German Institute for Japanese Studies entitled “Geeky-Girly Innovation: A Japanese Subculturist’s Guide to Technology and Design,” discussing ideas in his book of the same name due out in November via Stone Bridge Press.

So how much value does the Japan—perhaps, more accurately, the Tokyo—of today hold, with its armies of squeaky-voiced maids and big-haired, slim-waisted hosts moving as far away from the authoritarian/militaristic past as possible. A common argument is that this is a reaction against the old ways and a move towards Western culture. Not so fast, says Kawaguchi.

On the contrary, Kawaguchi postulates that “Japanese young people are not becoming Westernized, but [rather] more Japanese.” While pointing out that the way KFC Japan’s managers actually take a trip to a shrine to pay respects to the millions of chickens slaughtered in the name of Colonel Sanders is a reflection of the continuing mixture of the ancient with the modern is laughable, more considerable is the image that Japan has taken on in the world in comparison to its peers in the Western world. To this end, Kawaguchi looks for methods to the Japanese madness of moe.

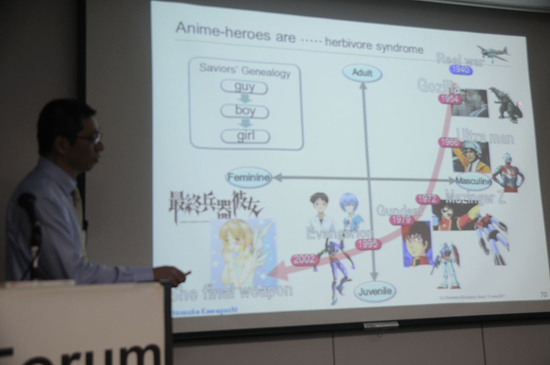

According to Kawaguchi, Germany and America focus on efficiency and performance and they have basically dominated this battle, leaving Japan—in something of a post-war complex stemming from occupation and a loss of militaristic power—to find a third way. Kawaguchi coins the phrase, “win by non-winning.” Instead of going for the jugular and showing one’s strength and performing the Hokuto Shinken equivalent of invention on the marauding biker gangs of the world, Japan’s way of the future is to be found in “helping the weak” and having the herbivore NEETs of the nation unite in a spirit of cooperation against the 60 missiles raining down on Tokyo.

The roots of this spirit can be seen even in the signage. Whereas various warning signs in the US/UK are relatively direct warnings, the signs seen in Japan and increasingly throughout Asia are on the more apologetic side, often featuring cartoon characters or cutesy animals. In a more absurd example, a technology used in Korea and Israel as a civilian-use lie detector was marketed as a “shy assist communicator” in Japan. Ditto the “Thanks Tail,” a remote-controlled dog tail added to the back of a car that can wag to show gratitude to drivers who let one pass on the road.

Kawaguchi acknowledges that this can go too far, showcasing how the Hayabusa satellite that recently returned to Earth was turned into a cutesy moe girl flying through space. More egregious perhaps are the Japanese Self-Defense Force mascots, Prince Pickles and Princess Parsley, who have about as much to do with Japanese military as Barney the Dinosaur. “These pathetic [for foreigners] characters hanging around. Everything becomes a OO-tan!”

A more philosophical take on this that Kawaguchi puts forth is “We are naturally living with faeries.” As New York and Paris focus on raw design, Tokyo can focus on the soul of things. Smaller cars and motorcycles are designed with menacing designs influenced by Gundam mecha to catch the eyes of drivers on the road to be more cautious, while larger ones are designed more gently to not startle. “The technician wants to go more exact… [but] the way to go is art.” Not for modern and ancient  to clash but rather to merge, as the bunraku puppet theater—once the domain of children and women—has been raised to a high art as representing old traditions in an age dominated by Hello Kitty.

to clash but rather to merge, as the bunraku puppet theater—once the domain of children and women—has been raised to a high art as representing old traditions in an age dominated by Hello Kitty.

Of course, the question of “Why?” is inescapable. Is it best for a nation which until recent history was defined by feuding clans and continuous internal and external conflict to become the herbivorous society? When the post-war Showa era still had Charles Bronson’s chiseled body selling us cologne on TV and Hayato Ichimonji’s Kamen Rider #2 providing a generation with a role model, Kawaguchi remains ambivalent about the changes of the Heisei, but philosophical about it. “I am not comfortable with it but trying to change it is meaningless. That’s the fact and I try to find some value out of it.”

Morinosuke Kawaguchi’s other lectures can be seen at his youtube channel.

Fernando Ramos is a Japan correspondent for Otaku USA. His photography site can be found at www.mroutside.com

![Doc Big in Japan Offers A Guide on How (or How Not) to Get Famous in Japan [Review] Doc Big in Japan Offers A Guide on How (or How Not) to Get Famous in Japan [Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/biginjapan01-480x360.jpg)