“Genocyber”. It’s one of those words that evokes a vivid impression of a time not so long ago—the early 1990s, when cyberspace was restructuring the very fabric of the known world. By the end of the 80s, girls-in-mecha, gross-out body horror and sci-fi were common features of manga and anime.

I was working on 16-bit games for the SNES & Genesis platforms at the time. Games/comics/anime and manga were relatively exotic compared to today and examples of extremity were keenly welcomed within the games community.

Such works were borrowing heavily from the perverse new realms of specialization emerging in porn, cinema, art, and literature. Put simply the sleazy hacker jacked in as Carpenter’s the Thing ripped tentacles from his screaming head. New sprouting fingers from the eyes formed legs and robots disemboweled each other to become the final and most powerful combination of pure machine and pure psychic energy.

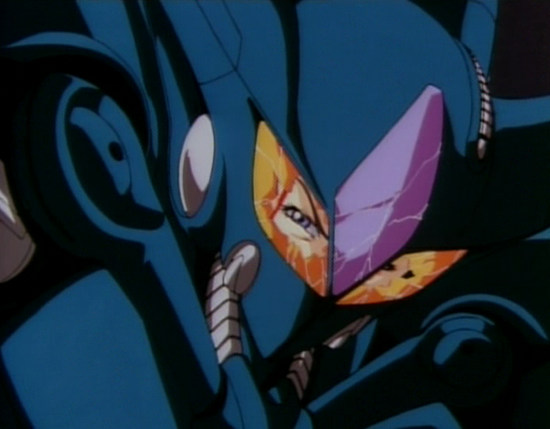

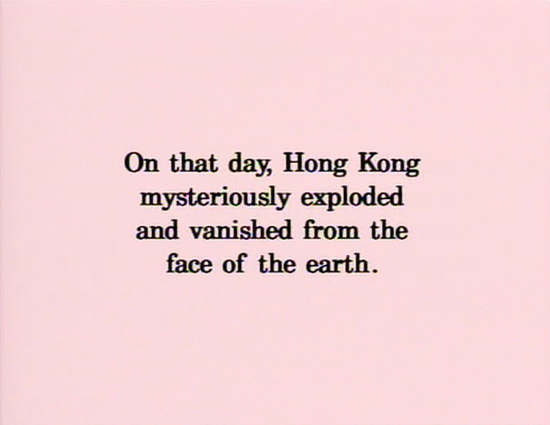

Genocyber 1 is the tale of two sisters, Elaine and Diana, who each control a mecha. One sister’s mecha only shows itself when a young girl who is protected by the mecha gets angry or faces danger. Elaine is a young mute girl who on the surface appears completely harmless. The moment she is hybridized with her weaker counterpart, she transforms into Genocyber, an entity that can destroy almost everything around her in a ten mile radius. A protective young boy with whom she is friends and shares psychic powers (a lovely scene shows them sharing an orange which she peels with telekinesis) is murdered by government agents. Elaine levels Hong Kong in revenge. Her attacks comprise mainly vicious sudden fire and flames that erupt spontaneously, like napalm.

Think about it. As Elaine you are a girl who cannot speak, but possess amazing psychic powers. People try to mess with you. You get angry. If you get angry enough, a mecha appears out of nowhere, invoked by your wrath, landing nearby as a protector. This mecha/protector/psychic girl entity has a sister who can invade the shared otherzone of their bond.

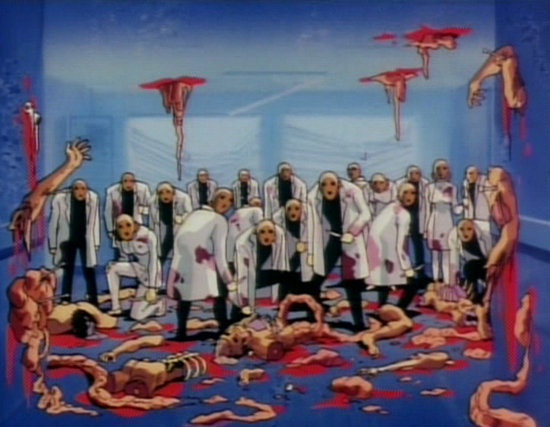

In an attempt to kill her sister, Elaine, Diana is helped by a mad scientist who has been commanding but has lost control of two robot cyborg assassins who massacre everyone between them and their target, Elaine. These expressionless sunglass-wearing ‘borgs use pulse weapons to render entire buildings slaughterhouses in their quest to locate Diana.

Visual Treatment: There is the standard wide shot of a place, life going on as normal. Then a sudden shock moment, like an explosion, and suddenly limbs are stuck to the ceiling, walls, and heads slowly unsnap from necks and roll onto the floor. You get the idea.

Overall feel: The film exudes menace. There are the depictions of sudden very public and very extreme events of visceral horror. The few sentimental bits involving the standard ‘dying-friend-waving-a-last-goodbye’ scenes, which, as bland as they are, still act as a nice breakwater to the Tsunami that is the remainder of the film. There are pure shock, sudden visual assault, mess-with-your-mind depictions of weaponized telekinesis and all it can bring. Ultra-violence for its own sake par excellence. Cyberpunk tech-noir flesh meat grind-porn, if you will.

Back when the internet itself felt like a new, viral and rather overwhelming cultural force that could at any moment grow multiple mixed-up body parts and rip through your world with shock and awe. Those few of us that logged on in 1993—and at the time it seemed to be basically you, me and five other guys we knew—felt we were privy to what was still something of a private world of inside jokes. Cyberpunk then was still a bit of an in-joke. It was something you shared that you had the satisfaction of knowing it, if kept extreme enough, would serve to isolate you from the real world out there. Otaku who liked Genocyber enjoyed the fact that the extremity of the horror on one hand expressed their own hangups about the world ‘out there’ as a place of real violence and shock and awe (this was the period of the first Gulf War, remember, evidence of the first corporate war on a major scale – itself very cyberpunk). But they also liked the idea of the body as a malleable, all-too-vulnerable ‘meat puppet’.

You had to be willing to rip out your own brains if you thought there were bugs crawling around up there (as happens in Genocyber 1 to a hapless cyborg in a subway), at least metaphysically. So cyberpunk anime of this strength was custom stuff. It was top-shelf. It was designed to offend, no doubt about it. Which is why it remains even today a little hard to find, and out of the way. This is dark stuff, but its darkness has a historical context. To understand this period, you need to understand 1993. The Internet just on the cusp of being a widespread cultural form. Grunge rock being a dominant music subculture, Public Enemy and hardcore hip-hop also at the forefront. Japanese popular culture in the west still not mainstream. Still a bit mysterious, exotic, underground. A rumor.

A lot of very weird changes were taking place in popular culture. The impact of John Carpenters classic The Thing can be seen in Genocyber 1, as can slasher and gore spectacles of the sort celebrated in magazines like Film Threat and Fangoria. Pornography in the mid-to-late 1980s was catering to every body combination imaginable, and the sheer range of body types on display and in circulation had exploded. By the time Genocyber was released in 1993 you had the now standard combination of horror and sci-fi (Alien, They Live, AKIRA), but you had a new dimension, a kind of cerebral-communication-through-neural-networks meme as well. Body mutilation, body destruction, body deformation were all fairly standard aspects of most popular culture aimed at teens and adults by the early 1990s, having emerged out of a 1980s of body fetishism of the sort that close-ups of Rambo’s and Arnie’s sweaty gun-covered muscular bodies (“like condoms stuffed with walnuts,” as Philip Brophy once described them). Shinya Tsukamoto’s Tetsuo: The Iron Man also set the standard for the speed and delivery of body mutilation as horror/comedy of visual visceral extremity.

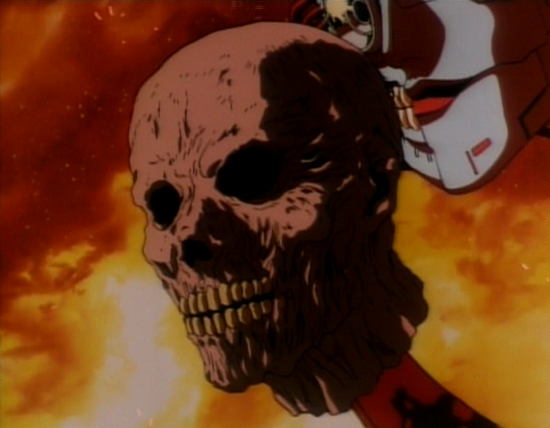

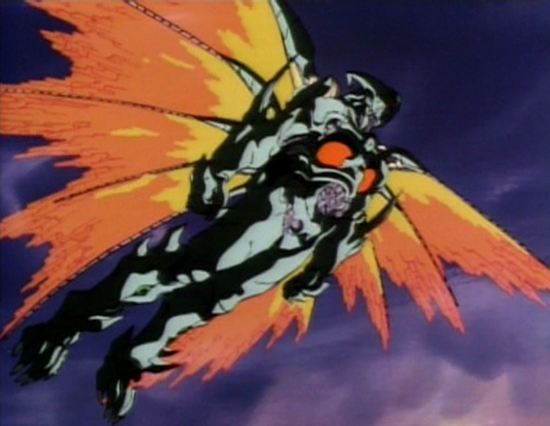

At the film’s climax, in a dazzling display of techno-fetishistic-polymorphous perversity, these robots, shrieking with psychotic laughter, start transforming. They extend their necks to sprout miniguns from between the jaws of screaming chrome skulls, all the while flying on King Ghidora-like golden wings of fire.

One triumphant mecha-girl pulls the other apart right down the middle like a telephone book in the hands of a circus muscle-man… The story is really only there to connect simply awesome scenes of mecha destroying cities and each other. See Genocyber—you won’t regret it.

Director: Koichi Ohata

Publisher: Us Manga Corps

Original Release Date: 1993

Follow David Cox online at https://www.davidalbertcox.com/

![SSSS.Dynazenon [Anime Review] SSSS.Dynazenon [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/16-9-SSSS.Dynazenon_Key_Visual_3.5-480x360.jpg)

![Back Arrow [Anime Review] Back Arrow [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/ba15-02686-480x360.jpg)