Two things are clear: one, Hayao Miyazaki will definitely never direct again, and two, Hayao Miyazaki might announce his next film tomorrow.

Those contradictory conclusions are at the heart of Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, the new documentary about the very contradictory Miyazaki – or more accurately, the three men who founded Studio Ghibli: friends/rival directors Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, and their producer, Toshio Suzuki. The film, directed by documentarian Mami Sunada, primarily chronicles the production of Miyazaki’s film The Wind Rises, as well as the simultaneous production of Takahata’s Princess Kaguya. Well, sort of.

Has Miyazaki really called it quits or will he continue? Kingdom doesn’t make the issue any clearer, but it does help to illuminate why the issue is so muddled to begin with. To put it simply, Miyazaki is complicated guy.

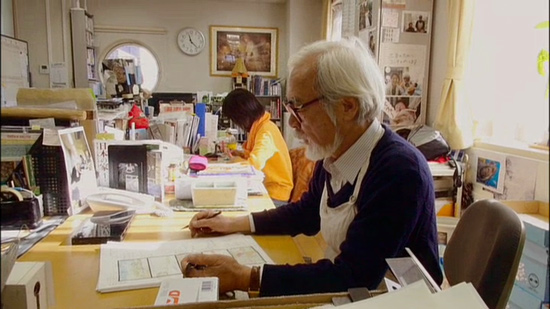

Here’s a man so confident in his craft, he doesn’t write scripts but goes straight into storyboarding, before he has any idea how the film will end. He sits with a stopwatch, and when he closes his eyes and hits the timer, the film unspools in his head.

On the other hand, as he sits and draws he reveals deep insecurities to Sunada about “whether there’s even a film here.”

“I really don’t know what I’m doing,” he repeats and repeats as he works. Later he reveals he considers himself manic-depressive and has to take sleeping pills to get any rest.

Here’s a man whose career has been based on making films for children, who throughout the film tells stories of his own childhood and of the children who he makes movies for, whose naivety and innocence he sees as a bulwark against the troubles of adulthood.

On the other hand, he has a famously strained relationship with his own son, director Goro Miyazaki, who makes a brief appearance in the film in which he does not come off particularly well, complaining about the conditions of a new project (probably Ronia The Robber’s Daughter).

Here’s a man insisting this is his last film, that no one can be expected to work like this at his age, that he’s really finished this time. He complains about being tired, burnt out, that he can’t do it anymore.

On the other hand, minutes before he’s to announce his retirement, he pulls Sunada over to the hotel window and narrates a potential short he’s just invented while looking out on the city.

“What if you leapt over that building, flew over that one and walked across that power cable? That’s the power of animation. Isn’t it wonderful?” he says.

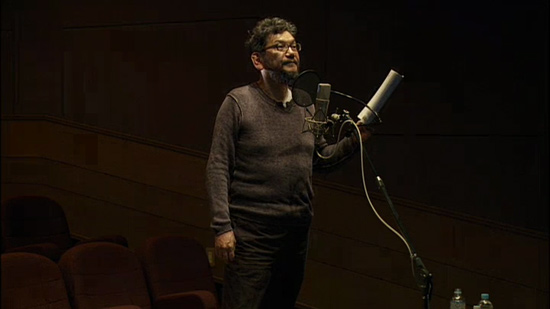

As much as the film is about Miyazaki, it’s also about the glue keeping the studio together, in the guise of Toshio Suzuki. We see Suzuki shuttling back and forth between the two Miyazakis, Takahata, and organizing press conferences, approving merchandise, and all the things besides filmmaking that need to get done to make a film.

“Miyazaki and Takahata didn’t even want to make these films,” he says. “It took four months to convince Miyazaki to do it.” Watching Suzuki wrangle these very strong-willed men, it becomes apparent without him around not a whole lot would get done.

There’s a lot more about the inner workings of the company – including some stories about people who’ve quit because Miyazaki is too hard to work with – and some really fascinating behind-the-scenes bits of the decision making behind Wind Rises, including the meeting where Miyazaki and Suzuki decide to use Evangelion director Hideaki Anno, rather than a professional actor, for their main character.

“What about… Anno?” says Suzuki, almost as a joke at first, but as the meeting rolls on the idea picks up steam. “Anno’s voice is really mysterious, isn’t it? It could actually work,” says Miyazaki. Seeing one of the great living anime directors get that light bulb over his head alone makes Kingdom worth the watch.

One man is strangely largely absent from the film – that’s Takahata, who’s simultaneously working on Princess Kaguya, but only ever appears in long shot or archival footage. It’s unclear whether this was a artistic choice to focus mainly on Miyazaki, or simply a practical one, as Sunada could only be in one place at a time.

In any case, though he doesn’t really appear in the film, his presence is felt through talk about him, especially from Miyazaki, who alternatively praises him as a genius and knocks him as a failed director.

Yet another contradiction, perhaps, from the king of dreams and madness.