Ocean Waves (Umi ga Kikoeru, aka I Can Hear the Ocean) is a made-for-TV animated movie from Studio Ghibli that was first shown on TV in Japan on May 5, 1993. It’s long been considered the “lost” Studio Ghibli film because it was never part of the package of Studio Ghibli films licensed to Disney in 1996 for worldwide distribution. When the Museum of Modern Art ran a then-“complete” retrospective of Studio Ghibli films in 1999 to coincide with the U.S. release of Princess Mononoke, Ocean Waves was not included. When I asked Steve Alpert, the U.S. rep for Studio Ghibli, about this at the time, he indicated that its status as a TV movie precluded it from being considered for theatrical distribution.

Twelve years later, in 2011, when GKIDS picked up the rights to a package of Studio Ghibli films for theatrical distribution in the U.S., the studio evidently had a change of heart and offered Ocean Waves as part of the package. When GKIDs’ New York International Children’s Film Festival staged a new retrospective of Ghibli films starting in December 2011, they included Ocean Waves as part of the series, giving the film its belated U.S. theatrical premiere at Manhattan’s IFC Center on December 29, 2011. The film was shown and projected on DigiBeta tape, since no 35mm film print exists. (I can make the argument that the film had a much earlier premiere when I showed it in my class on anime history at the School of Visual Arts on March 10, 1999. Back then I had to rely on a VHS fan-sub. When I showed the film again in a class I taught at City College in the fall of 2009 I used a subtitled DVD purchased in Chinatown.)

Ocean Waves is a remarkable film and one of the most intriguing high school dramas of all time, anime or live-action. It’s done in a realistic style, with great attention paid to character design in the creation of its various high school seniors and their family members and to background details in the depiction of the film’s setting, the city of Kochi in western Japan. It tells a plausible, character-driven story of Rikako Muto, a girl from Tokyo who arrives at Kochi High School as a transfer student in the senior class and proceeds to upend the friendship of two boys, Taku Morisaki and Yutaka Mitsuno, both of whom get entangled in Rikako’s willful antics and one of whom falls for her immediately, while the other initially puts up powerful resistance.

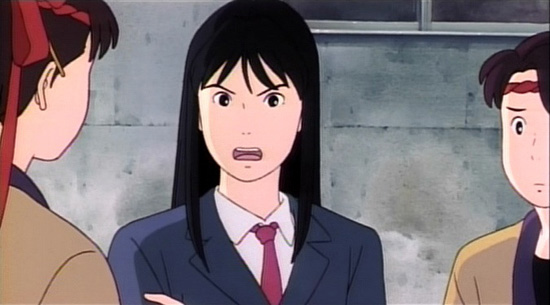

A beautiful brunette with high grades and athletic ability, Rikako has moved with her mother to Kochi after her parents separated and she desperately wants to return to Tokyo to live with her father. She embarks on separate campaigns to enlist the two boys’ unwitting help in amassing enough funds to enable her to do this and then befriends a shy classmate, Yumi, recruiting her to join her on a parent-sanctioned trip to Osaka to ostensibly attend a concert, but then switching destinations at the last minute so she can go to Tokyo to see her father. Yumi is horrified and calls Taku from the airport, seeking his help because he was the one who’d lent Rikako the money. Taku lets Yumi off the hook and agrees to accompany Rikako to Tokyo, where she introduces him as her boyfriend and begins a comedy of errors with much drama and equal measures of comedy as Taku gets embroiled in Rikako’s schemes. Back in Kochi, the two act as if nothing happened, yet rumors build, coming to a head as Taku and Rikako have a public confrontation involving slaps to the face, providing a stimulating dose of juicy drama for their classmates.

Rikako never quite earns the trust and friendship of the other classmates and proceeds to do what she wants, speaking plainly and forthrightly when challenged, leaving hurt feelings and a damaged friendship between Taku and Yutaka in her wake. There’s another dramatic confrontation about an hour into the film where Taku watches from hiding as Rikako is “prosecuted” by the other girls for her refusal to participate in class activities at the school festival. His sympathetic reaction to Rikako’s defiance earns the poor kid another slap. He just can’t get a break. Still, from this precarious foundation an unshakeable romance seems destined to emerge.

High school graduation doesn’t end the drama. Everyone goes off on their own, with Taku opting to attend college in Tokyo and Rikako curiously opting to stay in Kochi, but they all return to Kochi for a reunion a year later. Rikako is not there but it’s revealed that she went to Tokyo looking for “someone who likes to sleep in bathtubs,” a reference to the night she and Taku shared a hotel room during the Tokyo excursion, with a drunk Rikako getting the bed and poor Taku forced to sleep in the tub. With this, Taku finally gets his hopes up, leading to one of the most beautiful romantic endings I’ve ever seen in a movie. Rikako may be quite a handful, and some viewers may wonder what Taku sees in someone “who walks all over him,” as my daughter put it at the screening, but the turbulence around her is never boring and she’s notably hard to resist when she pours on her charms. Overall, it’s a gentle and moving slice-of-life drama, with plenty of comic situations, depicting the difficulty of young love and the circuitous path it often takes. I found much I could relate to.

A great deal of attention is paid to the fact that Rikako has a Tokyo accent and she finds the provincial Kochi dialect abrasive to her ears. She claims not to have understood anybody when she first transferred. She openly derides Yutaka’s hesitantly stated romantic designs purely on the basis of his accent. Two people are credited with “Dialect Instruction” for the voice actors.

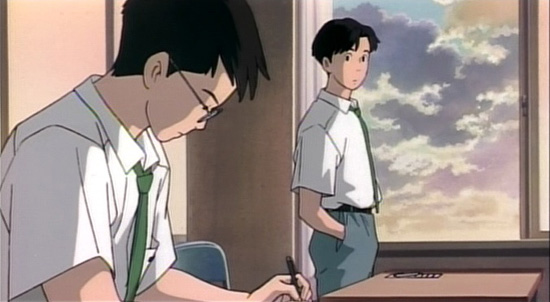

The character design delicately walks a thin line between making the characters look distinctly Japanese while giving them more subtly western features to distinguish them clearly from each other. In essence, they look Japanese, but with wider eyes. There are no blue-eyed blondes. And when the characters are shown at their reunion a year after graduation, they all look a year older. I don’t often notice this kind of attention in anime to the changes characters go through in the course of a short period of time. More importantly, the characters’ faces, though simply designed, express frequent changes in emotion quite clearly. We can see how they feel.

The film uses the streets, thoroughfares, malls and docks of Kochi as backgrounds. Kochi Castle, an actual local landmark, is seen clearly in the background in several shots, including one scene at night. When a co-worker told me he was visiting Japan one year and going to Kochi, I lent him this film to watch first. There is also a trip to Hawaii in the film, when the senior class makes their school trip there and Rikako makes her first (successful) attempt to manipulate Taku for her own ends.

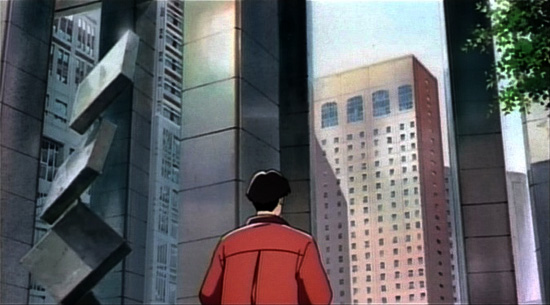

There are scenes in Tokyo as well. When Taku is pressed into duty as Rikako’s reluctant chaperone on her trip to see her father, he seems awestruck by Tokyo’s gleaming urban landscape. It’s not clear, though, if it’s his first visit to the city or not. When they arrive at the apartment building where her father lives and where she grew up, she describes how her ancestors owned the surrounding area when it was all farmland, so we get a sense of the enormous changes in the city and her connection to its past. We see a notable contrast between the eligible young men of Tokyo and their counterparts in Kochi when we meet Rikako’s fickle and stylish ex-boyfriend, who’s now dating Rikako’s best friend. Taku seems a lot more manly and grounded in comparison. Responsible and dependable, he’s also obviously the better catch.

The soundtrack is dominated by a single melody, composed by Shigeru Nagata, which is repeated multiple times in different arrangements, culminating in a song at the end beautifully sung by Rikako’s voice actress, Yoko Sakamoto, who has only one other voice acting credit on Anime News Network.

The film was directed by Tomomi Mochizuki, who’s better known for his directing work on Maison Ikkoku, Kimagure Orange Road, and Ranma ½. The crew included such Studio Ghibli regulars as Katsuya Kondo, who did character design and animation direction and has worked on a dozen other Ghibli films; Naoya Tanaka, the art director, who has done similar duties on eleven other Ghibli films; and Yoshifumi Kondo, credited with design, who went on to direct the one other Ghibli masterpiece that wasn’t directed by Hayao Miyazaki or Isao Takahata, Whisper of the Heart (1995).

As of this writing, there are no plans to release the film on DVD in the U.S.

(Special thanks to Eric Beckman, founder and president of GKIDS and co-director of the New York International Children’s Film Festival.)

![Lady Oscar: The Rose of Versailles [Anime Review] Lady Oscar: The Rose of Versailles [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/RoV_Vol2_Front_CoverArt_V1-480x360.jpg)