From now until the end of the year, Otaku USA e-News presents 98 Degrees: a deep dive straight into the anime of 1998. Which greats of ’98 would you like to see covered? Comment below or drop our editor a line.

From now until the end of the year, Otaku USA e-News presents 98 Degrees: a deep dive straight into the anime of 1998. Which greats of ’98 would you like to see covered? Comment below or drop our editor a line.

“Why? Why won’t you come?”

A schoolgirl slumps against the wall of an alleyway, hyperventilating, caught in the grip of a panic attack. Behind her, a group of older girls point and laugh. Check it out: that kid’s wasted!

“Don’t play hard to get! Let’s go some place happy!”

A businessman makes a grab for his young female companion’s ass and she fights him off.

“I don’t need to stay in a place like this.”

Silently mouthing these words, junior high school girl Chisa Yomoda drops from a rooftop, tearing through the wires that crisscross the streets, into a seedy back alley in the Shibuya red light district.

The businessman and his companion’s kiss is interrupted by a crash. Chisa’s arm leaks blood into a puddle. Anonymous voices rush to distance themselves.

“I don’t know! It’s got nothing to do with me!”

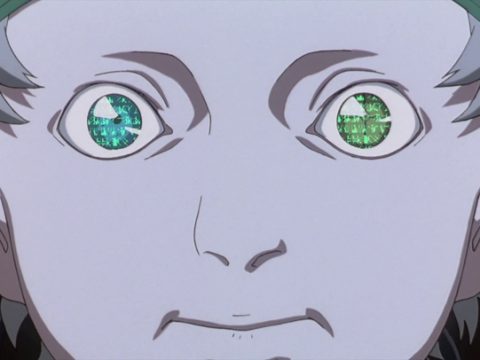

The death that opens 1998 techno-horror anime Serial Experiments Lain is threaded through with desperate entreaties for connection and attempts at disassociation that range from mocking to panicked. Common to all of them is a sense of alienation – this place is no good; let’s go somewhere happy.

The death that opens 1998 techno-horror anime Serial Experiments Lain is threaded through with desperate entreaties for connection and attempts at disassociation that range from mocking to panicked. Common to all of them is a sense of alienation – this place is no good; let’s go somewhere happy.

It paints a world where the skies are caged by wires, the sound of electricity humming through the streets, crackling with sinister portent. It’s a world overloaded with enough information to break a person’s mind into fragments, where lies, fantasies and conspiracy theories are made real by the words of online prophets, where faces in the street become ghosts and fade to nothing, while the dead snap into clear focus right before your eyes—neither present nor absent, dead nor alive. Hiding behind all this confusion, couldn’t there be a better place if we were just able to scratch beyond the surface?

A self-driving car tears through a crowded intersection, again in Shibuya, causing one fatality. The accident is believed to be due to a malfunction in the VTCZX road traffic information transmission system.

Serial Experiments Lain insists it’s happening now—present day, present time—and the world of 2018 can feel eerily similar to the fragmented, confused, disassociated, unreal life that Lain’s characters drift through.

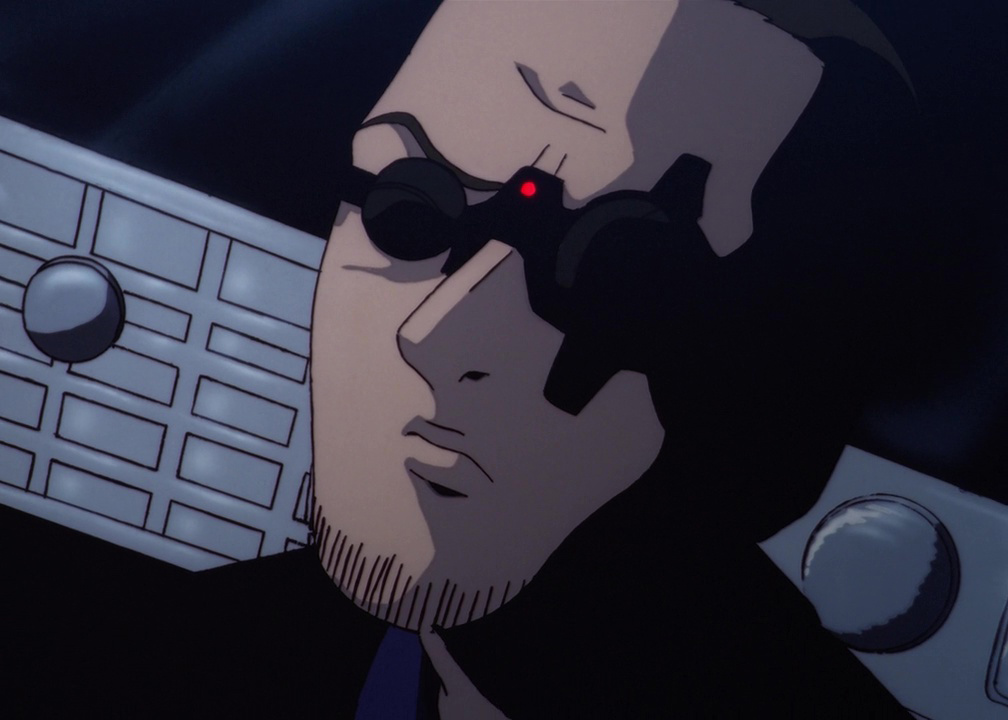

Nothing is lost on the Wired (as the web is called in Lain’s world). As the character of Professor Hodgeson discovers, there’s no dark secret that can’t be dragged back into the light, and no matter how over it you feel, it is always trapped in a hyper-real now as far as the Wired’s concerned. As the sinister hacker collective known as the Knights discovers, you might be the immortal black riders of the Dark Lord online, but one well-timed doxxing and your IRL lives are in tatters, or maybe even over.

The physical world, with all the pressures and stresses of daily interactions with other humans, navigating their secrets and sensitivities, society’s rules and conventions, can be terrifying and alienating. Maybe you’re not one of the popular kids. Maybe you don’t fit the arbitrary-seeming template of a good member of society. It’s not a surprise, then, that a hyper-connected online world increasingly offers its own paths towards a kind of acceptance for the lost and rejected. Join us: the answers are here, God is here, you can be one of the chosen ones.

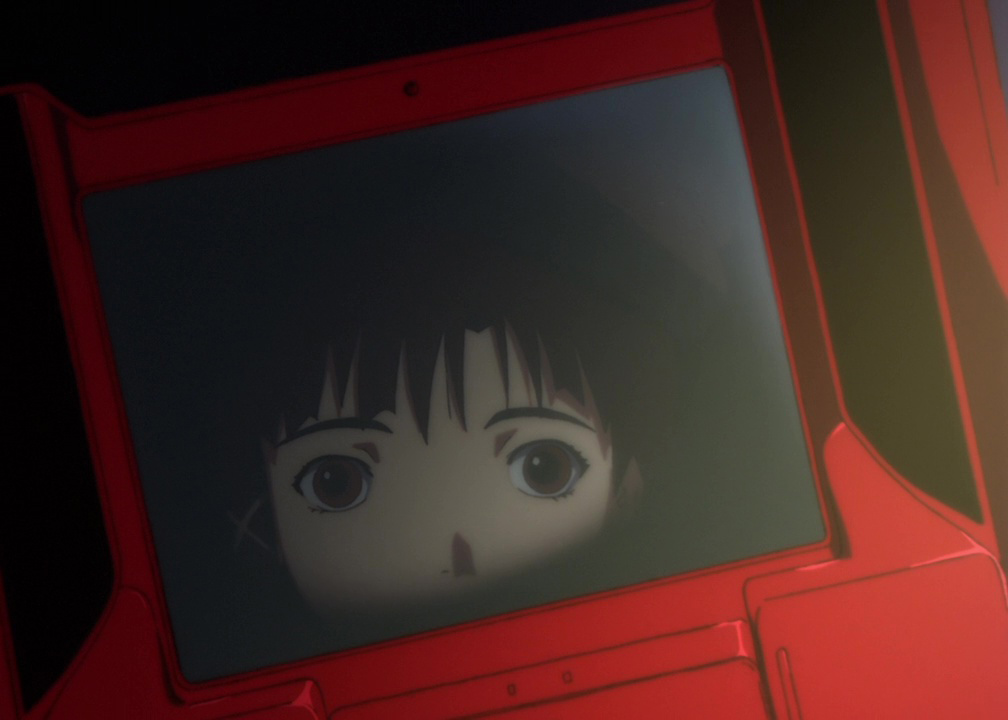

A socially awkward teenage girl giggles with delight at a technological joke delivered by one of her anonymous new online friends. They’ve been helping her out with her new interest in computers, guiding her, making her feel at home. Her friends at school are worried about her, but she’s never felt accepted like this before.

A socially awkward teenage girl giggles with delight at a technological joke delivered by one of her anonymous new online friends. They’ve been helping her out with her new interest in computers, guiding her, making her feel at home. Her friends at school are worried about her, but she’s never felt accepted like this before.

“Why are you guys so nice to me? No, it’s not like that. It’s just a bit strange: I don’t have many friends…”

In 1998, as much as Lain was speaking to the future, it was also speaking to very present concerns. Five years earlier, 76 people had died in the FBI raid that brought to an end the siege of the Branch Davidians religious sect headquarters in Waco, Texas. Three years earlier, the Aum Shinrikyo sect carried out a poison gas attack on the Tokyo metro, eventually resulting in the deaths of 13 people. One year earlier, 39 members of the Heaven’s Gate UFO cult in San Diego, California knocked back cocktails of phenobarbital, apple sauce and vodka, then suffocated themselves with plastic bags.

The way that cults prey on social misfits and those who feel marginalised by mainstream society was very much at the forefront of the public imagination in the 1990s, with the onrushing millennium and growing panic over the Y2K Bug adding a technological edge to apocalyptic paranoia. While not commenting directly on these events, the religious aspects of Lain nonetheless wedded its technological concerns to this atmosphere of millennial religious anxiety.

The growing adoption of mobile phones, and particularly the widespread use in Japan’s urban areas of cheap, accessible PHS phones by teenagers, had created a moral panic of its own as well. Kids with access to personal communication technology, free from the mediating influence of parents, had been an ideal breeding ground for tabloid tales of teens gone wild. The phenomenon of “telephone clubs,” where men could pay for access to a phone booth that would put them in contact with the mobile phones of girls interested in “subsidised dating” became notorious for its association with teen prostitution.

Again, while not commenting directly on the issue, the image of very young, apparently well-brought-up girls like Alice, Juri, Reika and Lain using their handheld navis to meet up and sneak out to clubs tapped into contemporary anxieties over the independence new technology was affording youngsters.

A little girl in bear pajamas descends the stairs. Her parents stand in the doorway, locked in a deep kiss and embrace. She watches them for a moment, before her father notices they have been seen. He greets his daughter, as his wife casts a resentful sidelong glance at the girl.

A little girl in bear pajamas descends the stairs. Her parents stand in the doorway, locked in a deep kiss and embrace. She watches them for a moment, before her father notices they have been seen. He greets his daughter, as his wife casts a resentful sidelong glance at the girl.

Both an intensely private and fundamentally shared experience, sex is a recurring theme in Serial Experiments Lain that lies at the heart of one of the show’s central conflicts—between the desire to connect and the instinct to isolate oneself from others.

Lain herself is emotionally almost completely inaccessible—both to the viewer, to her family and to her friends—and her few moments of physical intimacy come where people push against her barriers, like when like her hacker contact Taro steps back across her room and steals a kiss from her, or when her friend Alice reaches across to place Lain’s hand on her chest and feel her heartbeat.

These ambiguous, private-yet-shared moments are a fragile, emotionally complicating challenge to the overwhelming, fanatically simplistic, one-size-fits-all shared consciousness of the Wired. Chisa Yomoda’s falling body interrupts a kiss, Lain’s sister Mika skips school to have what one can only imagine is pretty desultory sex with her older boyfriend, Lain averts her eyes from the sexualized bunny girl avatar of an online contact, Alice’s private masturbation fantasies are broadcast to the school and strain her friendship with Lain, Lain’s interactions with Taro are always under the ever-present shadow of his girlfriend Myu Myu’s jealousy—the intrusion of sex into the story always breaks down one barrier but throws up another. Lain’s own (ambiguous and confused, but at least on some level sexually-charged) love for Alice means that she can’t allow her to be absorbed into the collective consciousness she creates.

Secrets and privacy are as much an abomination to the institutions that govern our online world as they are to the Wired of Serial Experiments Lain. Our televisions, smartphones and microwaves spy on us, our every online interaction is filed away and processed for monetization—we live surrounded by a constant electrical hum of data detailing every aspect of our lives. We are constantly urged to connect, until the point where we take it for granted that we are always connected, always under some kind of surveillance, delighting in the validation we receive from it.

Secrets and privacy are as much an abomination to the institutions that govern our online world as they are to the Wired of Serial Experiments Lain. Our televisions, smartphones and microwaves spy on us, our every online interaction is filed away and processed for monetization—we live surrounded by a constant electrical hum of data detailing every aspect of our lives. We are constantly urged to connect, until the point where we take it for granted that we are always connected, always under some kind of surveillance, delighting in the validation we receive from it.

A teenage girl in a plain white dress stands outside Shibuya Station talking to another version of herself. She stands on opposite sides of a train carriage continuing the conversation. She watches her reflection and sees another version of herself in the background. She stands in a classroom among the unreal figures of hunched up students on an empty street. In a blank, cold limbo, she sits at a table, floating in the sky while her father sits opposite and quotes Proust.

Lain uses an array of hallucinatory visual and editing devices to stitch together a dizzying collage of images and ideas that wouldn’t make even the faintest amount of sense and would have seemed rife with gaping omissions if arranged in a more clinical and logical manner. Its prophesies about the implications of online culture may seem with hindsight striking in their accuracy, but they were by no means uniquely original observations at the time.Ghost in the Shell had visited similar places, and critical theory, made phenomenally popular in Japan in the ’80s by the critic Akira Asada, had laid a lot of the theoretical tools for understanding what the Wired delivered. In a way, it’s remarkable how easy it was, by the late-’90s, to predict a lot of where the web would take us.

So, like this article,Lain is nowhere near as clever as it sometimes pretends to be. However, while it doesn’t have the intricate plot mechanics of modern puzzle-box TV shows like Westworld, it’s in many ways a far stranger, more interesting and more rewarding creature.

It emerged out of a strange period in anime history when it was apparently the law in Japan that all anime had to be written by scriptwriter Chiaki J Konaka (in 1998 alone, he also worked on Bubblegum Crisis Tokyo 2040, Vampire Princess Miyu, Devil Lady, Gasaraki, Catnapped! and Fushigi Mahou Fan Fan Pharmacy), so it’s easy to imagine him tossing off pages of the script, a frantic, insomniac haze of deadlines and caffeine turning the show into an exercise in automatic writing.

It emerged out of a strange period in anime history when it was apparently the law in Japan that all anime had to be written by scriptwriter Chiaki J Konaka (in 1998 alone, he also worked on Bubblegum Crisis Tokyo 2040, Vampire Princess Miyu, Devil Lady, Gasaraki, Catnapped! and Fushigi Mahou Fan Fan Pharmacy), so it’s easy to imagine him tossing off pages of the script, a frantic, insomniac haze of deadlines and caffeine turning the show into an exercise in automatic writing.

The result is maybe closer to the delirious meandering through images and philosophical themes that you find in 1970s acid nonsense like Alejandro Jodorowsky or in the I Ching-directed paranoid gnostic sci-fi of Philip K Dick. It has echoes closer to home as well, though. Many of the visual devices Lainemploys share something in common with other willfully brain-melting anime of the same general era, like Neon Genesis Evangelion, Revolutionary Girl Utena and Perfect Blue. Sharp cuts from one location to another that appear to leave the main character as disorientated as the viewer; flat, layered, symmetrically ordered compositions and editing at right angles; harsh shadows and blown-out highlights; hypnotic repetition of the same sequences and images. The extent to which the staff on these shows were cribbing from of each other’s work is debatable, but they were at least drawing from a similar pool of visual influences that would have included the likes of David Lynch, Jean-Luc Godard and Japanese avant-garde filmmaker/playwright Shuji Terayama.

Unlike Evangelion or Perfect Blue, it’s hard to pin down the long-term impact of Serial Experiments Lain. It wasn’t a big hit in Japan, although it certainly had its fans. The creative team of Konaka, director Ryutaro Nakamura, producer Yasuyuki Ueda and character designer Yoshitoshi Abe would reconvene in various combinations and through various genres to infuse NieA_7, Ghost Hound, Texhnolyze, Kino’s Journey and Haibane Renmei with a peculiar affecting, eerie, melancholy surrealism, while the death of Nakamura in 2013 left reunion project Despera in production hell.

There is also perhaps a distant echo of Lain’s teenage solipsism in fellow lonely god Haruhi Suzumiya. Meanwhile, over in Hollywood, there are striking similarities to Lain in teen fantasy drama Donnie Darko. Like Lain, Donnie is plagued by visions of ectoplasmic serpents snaking around his classroom, and like Lain, he resolves that the only way to save the world is to erase himself from it. The portentous electrical crackle and hum that runs through David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: The Return will also feel eerily familiar to some. Drawing a direct line from these works to Lain might be a stretch, but it’s not impossible to imagine the influence of this extraordinary show lingering on, partly remembered, in the collective unconscious.

Ian Martin is the author of Quit Your Band! Musical Notes from the Japanese Underground.