Madhouse is one of the most venerable anime studios out there. From the minds and hard work of former Mushi Pro (Astro Boy, Dororo, Kimba the White Lion) animators like Masao Maruyama (see our MAPPA feature), Yoshiaki Kawajiri, Rintaro, Osamu Dezaki, and others sprang forth lauded productions ranging from The Dagger of Kamui and Ninja Scroll to 2011’s Hunter x Hunter anime, this season’s Death Parade, and beyond.

It’s impressive that a studio with so many revered classics continues to push anime forward, with films like Takeshi Koike’s Redline bucking trends and going straight for what made quite a few folks fall in love with anime in the first place. It would take an entire devoted line of magazines to chronicle what Madhouse has accomplished over the years, but for now having a few of our contributors step in to put the spotlight on a handful of high points will have to do.

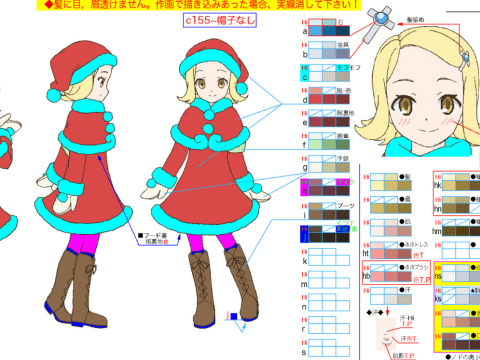

The Dagger of Kamui

[ By Daryl Surat ]

One of Madhouse’s co-founders is the legendary Rintaro, who’s been working in the anime industry since the start of its modern incarnation: 1958’s Panda and the Magic Serpent. Few will deny that Rintaro is one of anime’s grand masters, as he’s directed some of the greatest anime titles in history. But here’s the thing: he’s also directed some of the worst. What’s more, nobody can ever quite agree on which of his works fall into which category!

I’ve seen 1985’s The Dagger of Kamui listed on just as many “best anime ever” lists as “worst anime ever” ones. Clocking in at just under 2 hours and 15 minutes, I’m completely enthralled the entire time, while others are bored to tears. It’s a historical fantasy ninja epic—that’s “epic” in the true, literary structural sense of the word—with a look and sound unlike any anime ever made prior to it or since. We may all claim to want innovation in cinema, but actually doing it incurs the risk of strong polarizing reactions from an audience. Consider the soundtrack: a fusion of classic rock, funk, and Ainu folk vocals where Ramayana monkey chants are used to signify ninjas on the attack. You’ll either find it super cool or tremendously irritating. Such is the filmography of Rintaro.

The Dagger of Kamui has nothing to do with Sanpei Shirato’s gekiga classic, The Legend of Kamui, which got adapted into a (bad) live-action film in the late 2000s. Dagger may start as a tale of a boy training in the mystic shinobi arts, but it soon becomes a globe-trotting saga of pirates, cowboys, Indians, and ninjas galore. It was the mid-1980s, so “ninja” still mostly meant guys covered up from head to toe doing acrobatics, moving stealthily, using illusions and disguises, and hurling shuriken with extreme force. This is in stark contrast to most ninja anime, where “ninja” may as well just mean “mutant.”  As a work of historical fantasy, our leading man Jiro ends up crossing paths with actual people and becoming involved with actual events, though since most of them are Japanese figures we don’t recognize, American audiences tend to only remember this film as being “the one where Mark Twain shows up.”

As a work of historical fantasy, our leading man Jiro ends up crossing paths with actual people and becoming involved with actual events, though since most of them are Japanese figures we don’t recognize, American audiences tend to only remember this film as being “the one where Mark Twain shows up.”

The Dagger of Kamui has been available in America for decades in one form or another. In the era of VHS tape it got released under a few different names, often with significant edits due to the sustained violence—ninjas are dismembered, beheaded, and sliced in half CONSTANTLY—and brief female nudity. Fortunately, AnimEigo released an uncut Japanese-only audio edition on both VHS and DVD (back in the pre-Metropolis days when the director was still credited as “Rin Taro”), which remains in print to this day. Still $8 new, direct from their website! Sadly, there’s never been a Blu-ray release of the film, even in Japan.

Love it or hate it, you owe it to yourself to watch The Dagger of Kamui if only so you can understand what one of Ryuko Matoi’s mid-series special attacks from Kill la Kill is a direct reference to. Narratively, visually, aurally, Dagger’s the sort of anime film that only Madhouse would ever fathom producing, and on top of that they double featured it with one of the most eclectic and visually experimental anime titles ever: the 45-minute Bobby’s Girl, aka Bobby’s In Deep. That one never saw an official US release or got a Blu-ray (or DVD!) release in Japan either, but fan translations are out there.

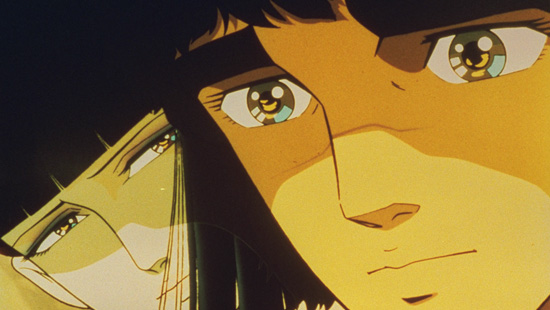

Ninja Scroll

[ By Paul Thomas Chapman ]

A secret shipment of gold sparks of an all-out ninja onslaught in Yoshiaki Kawajiri’s landmark action film Jubei Ninpucho, better known in North America as Ninja Scroll. A straightforward story of duplicity, revenge, and the supernatural, Ninja Scroll follows Jubei Kibagami, a shinobi with neither clan nor master, as he is dragged unwillingly into a confrontation with the demonic Eight Devils of Kimon, culminating in a showdown with an enemy whom Jubei had thought he’d slain long ago.

Kawajiri’s cinema is the cinema of the night. Animation cels are his canvas and darkness and shadow are the pigments with which he paints his scenes. Ninja Scroll is a film defined by the interplay of two colors: black and blue. Few films evoke a more stylish, otherworldly atmosphere than the world Kawajiri and the animators of Madhouse create in this movie, a world in which ninjas race through haunted forests and midnight mountain paths beneath a wan and baleful moon.

The darkness of Ninja Scroll is not merely an aesthetic choice, but also a symbolic one. It is the darkness of the human spirit, where greed and envy and ambition inspire all manner of base betrayals. Kawajiri’s films are full of stoic heroes who struggle against the darkness both within and without. Jubei Kibagami, the protagonist of Ninja Scroll, is one such hero. Despite his dry sense of humor and penchant for understatement, Jubei has felt the sting of tragedy and treachery. His darkness resides just beneath the surface. Kawajiri represents this dual nature visually: even during daylight scenes, Jubei’s face is usually half-cloaked in shadows.

While black and blue dominate the color palette, Ninja Scroll is also a film that runs red. The action sequences are fantastical, hyper-stylized, and undeniably gruesome. The violence of this film slices flesh, sprays blood, breaks bones, severs limbs, and cleaves skulls asunder. Swords flash like lightning and shurikens fly like lethal hailstorms. Life is cheap and loyalty is even cheaper, and ninjas die miserably by the boatload.

Ninja Scroll seasons its action with a healthy dose of body horror. In this film, the art of ninjitsu twists and warps the practitioner in unnatural ways, until the human body becomes a protean thing. The Eight Devils of Kimon each demonstrate hideous, transformative powers: Tessai can harden his flesh into stone, turning him into a murderous juggernaut on the battlefield. Benisato can shed her skin like a snake, and her body is a home to vipers. Mushizo’s hunched back is a hive brimming with hornets. Shijima can melt into the shadows and manipulate people as if they were marionettes. Yurimaru is a living dynamo capable of electrocuting his foes. Zakuro can convert human beings and animals into walking bombs. Gemma, the leader of the Eight Devils of Kimon, is capable of regenerating from even the most grievous of injuries. It’s not just the villains that contribute to the idea of the human body as something polluted and strange, though. Kagero, a kunoichi and poison-tester in the employ of the chamberlain, is so impregnated with venom that she’s incapable of physical intimacy for fear of poisoning her lovers to death. Even Dakuan, the government spy posing as a itinerant monk, is capable of some bizarre and grotesque transformations.

Ninja Scroll is an “evergreen” title. Its influence and cultural impact are still felt more than 20 years after its initial release. Its violence and its sexual content feel even edgier today than they did back in 1993, to the point where on the accompanying commentary track even the film’s creators seem shocked and a bit chagrined by the numerous scenes that assault the senses and offend the conscience. Ninja Scroll is an artistic triumph and a loving tribute to the nihilistic jidaigeki films of the 70s. It has carved a place for itself in anime history and cemented Kawajiri’s legacy as a master of hard-boiled action cinema.

Cardcaptor Sakura

[ By Brittany Vincent ]

In the realm of magical girl animation, one series stood out among the rest in Madhouse’s stable: Cardcaptor Sakura. Ten-year-old Sakura Kinomoto was just an elementary school student, but she was entrusted with the fate of the entire world after setting the sentient Clow Cards free. This was a series that challenged convention, forcing a young heroine to work alone, aside from her mascot character, for a good part of the series, while forming rivalries and romances along the way that were decidedly more adult in nature than many of the series’ contemporaries. What’s more, the series never took itself too seriously, taking time out for Sakura to learn lessons about friends, family, and budding romances, even exploring facets of same-sex admiration and romantic feelings from Sakura’s best friend Tomoyo, depicting these affectionate relationships in a positive and encouraging light.

Spanning 70 episodes with a movie and a rabid fan base, Madhouse’s gentle yet reassuring magical adventure is a classic in the shojo genre, with plenty to offer fans of action, romance, and everything in between. It’s no surprise that, like Sailor Moon, new and revamped merchandise is being pumped out on a near-constant basis, with a recent Blu-ray release complete with a new English dub track so a whole new generation of fans can find something to love. It may be on the less popular end of things compared to Sailor Moon and today’s Puella Magi Madoka Magica, but it’s still by all counts an exhilarating and exciting series and a boon to Madhouse’s stable.

Black Lagoon

[ By Daryl Surat ]

So much of anime comes from pre-existing source material such as light novels or manga, but when fans hear that Madhouse is handling adaptation duties there’s a collective sigh of relief. That’s because the studio’s approach is by and large “retell the manga word-for-word, scene-for-scene while improving the artwork and adding appropriate audio.” Monster and the first batch of Hellsing Ultimate episodes are but two such fine examples from the past decade, and those of us who were around for the decades prior can confirm those aren’t outliers.

Black Lagoon is another, and for the record it does NOT feel like that anime first came out nearly 10 years ago. That’s because Rei Hiroe’s “babes and bullets” manga about modern-era mercenary pirates operating throughout Southeast Asia is still ongoing, and for good reason: it’s one of the best action series in recent years. We’ve reviewed this one multiple times before, but if you’ve never heard of it, just imagine if Gunsmith Cats remained focused on the action and the hardware throughout its run and never ever decided it was far more interested in sexualizing underage girls. That’s Black Lagoon: a grandiose R-rated homage to American and Hong Kong action cinema. Ain’t anime grand?

It is one thing to make sure the art remains on model and the story plays out like how people expect when adapting manga into anime. But the Madhouse difference lies in the talent for filling in the spaces between panels and understanding how to pace events in motion. Much as I love One Piece and World Trigger, excellence in that aspect is what’s missing so often from their Toei-produced anime incarnations. Director and screenwriter Sunao Katabuchi is a stickler for background detail work (see interview) and that, combined with the pacing, is what keeps Black Lagoon so consistently enjoyable to watch. Katabuchi’s over at MAPPA these days, so if future installments get made, it’ll be interesting to see how they turn out and whether he’ll have any involvement.