Shout At The Devil!

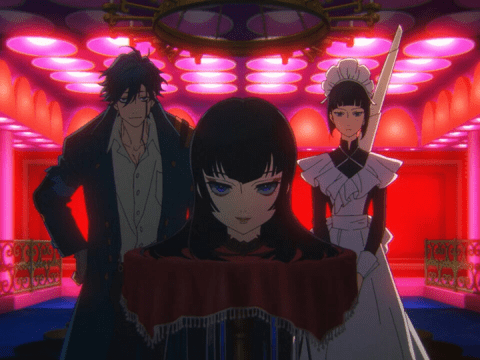

I never would have guessed that in the year 2018 the first anime title to generate a frenzied otaku reaction would be the latest revival of a Go Nagai classic from the early 1970s as interpreted by historically polarizing and noncommercial auteur Masaaki Yuasa, but I’m glad it happened. For decades animation fans, skaters, punks, metalheads, and other pop cultural miscreants have been drawn to Devilman, the demonic Japanese “superhero” whose sacrilegious premise, gruesome violence, and explicit sexuality was practically guaranteed to freak out your parents. Now, like so many recursive cycles of destruction and rebirth, it’s happening again for a new generation. DEVILMAN Crybaby is simultaneously a drastic modernization of the original manga storyline and perhaps the most faithful animated adaptation of it.

Released worldwide in its entirety of an unconventional 10 episodes, DEVILMAN Crybaby is in a sense reminiscent of classic OAVs of yesteryear. It’s thanks to online video streaming platform Netflix, as its funding of projects for exclusive distribution gives creators more freedom. No multitudes of sponsors to keep happy, no broadcast decency standards to adhere to, and with Netflix accounting for a massive percentage of all Internet traffic total, unlike OAVs the visibility extends far beyond dyed-in-the-wool anime otaku. At the reins are director Masaaki Yuasa and longtime partner in crime Eunyoung Choi, who after years of blowing minds on commercially overlooked gems now have their own studio, Science SARU. Their past movies Night Is Short, Walk On Girl and Lu Over the Wall are now set for US release from GKIDS Films in the wake of DEVILMAN Crybaby’s popularity.

For decades the main thing anyone ever knew about Devilman was its nihilistic ending, but since most viewers of Crybaby are brand new to it all I’ll just stick to this incarnation: Akira Fudo was a meek teenager on the track and field team until one day his sociopathic childhood friend Ryo Asuka returns from overseas with his fancy car, expensive coat, and machine gun to invite Akira out to one of those secret underground parties where TEENAGERS TAKE DRUGS AND HAVE SEX that everyone you know goes to except for you. With all the “acceptable slasher movie victim” sins met, next thing you know Ryo is stabbing random people with a broken bottle to provide the requisite demonic blood summoning. For demons are real, possess humans, and cause people to morph into nightmarish forms that slaughter and bang indiscriminately. (Demons also bleed what appears to be mustard.) But weepy empathetic Akira, upon being possessed by the demon Amon, is able to overcome evil’s influence and instead retain his human heart while possessing demonic strength … a Devilman! All manners of sinful, morally objectionable content are on display in DEVILMAN Crybaby … but enough about the first episode!

With Ryo’s expertise Akira now has the power to bring the war to them, and Ryo is sure to record Akira’s exploits on camcorder all the while. So THAT’S how Card Captor Sakura came about! But even when not transformed, becoming a Devilman means Akira experiences drastic physical changes not only to height, speed, and musculature but also crotch bulge: in the past while he’d at least try to be discreet about watching porn, he now fearlessly watches at full volume on a giant projector in the school’s A/V room. MORE LIKE “AV” ROOM. Yet his empathy persists: like the tattooed assassin Crying Freeman, Akira cries heavily in consideration of the suffering the demons inflict and the dark heroism he must pursue.

Certainly, DEVILMAN Crybaby is lurid. It also features depictions of the Biblical Satan and God that may not necessarily align with what they teach in Sunday school. If you condemn media for being “problematic” then you probably shouldn’t watch. Still, that’s all window dressing. What drives DEVILMAN Crybaby mania is that it’s emotionally devastating and thematically heavy like Madoka Magica, Revolutionary Girl Utena, and Neon Genesis Evangelion (which was itself influenced by the original Devilman).

The key is characterization, not just of Akira and Ryo but of the entire supporting cast. Akira’s would-be love interest Miki Makimura is reimagined as the most fundamentally “good” character of the series. Miki Kuroda, Makimura’s slightly less fast and significantly more endowed teammate, resents the fact that she’s second banana to the point that everyone calls her “Miko” instead. Koda, like Akira, is a high school track star struggling with his true nature. Even the delinquents from the original are back, reimagined as freestyle rappers whose lyrics offer insights into the current state of affairs. If anyone gets short shrift, it’s the classic Devilman villains who are typically resigned to brief appearances before meeting their ends. Regardless, the Crybaby incarnations of Silene (inspiration for Kill la Kill’s Ragyo) and Psycho Jenny leave a memorable impression.

I was drawn to how the aesthetic synthesis of Masaaki Yuasa with Go Nagai resulted in DEVILMAN Crybaby, modernizing a classic while revising it to tighten up the original on the fly plotting. It was also quite humorous quite often, which is not something you’d expect given everything I’ve just described. But many strongly resonate with Crybaby for its emphasis on explicitly gay and lesbian characters in a dramatic presentation. Perhaps those are the same thing, though! For while even Go Nagai had to abide by content restrictions—Devilman was originally a Weekly Shonen title—much of Crybaby’s thematic framework was present in his original 1970s manga, which American fans only now have legal access to as he celebrates his 50th professional anniversary. If you’re inspired by DEVILMAN Crybaby to check out Yuasa’s other works from the 2000s and peer into the wild world of Go Nagai, then I consider myself as having successfully passed on the baton.

DEVILMAN Crybaby is available from Netflix.

This story appears in the June 2018 issue of Otaku USA Magazine. Click here to get a print copy.