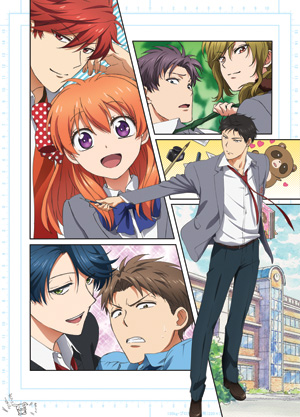

The course of true love never did run smooth, to borrow a line from Shakespeare, but few relationships have such backwards beginnings as the one that blossoms between high school students Chiyo Sakura and Umetaro Nozaki, the protagonists of Monthly Girls’ Nozaki-kun. Driven to confess her feelings for her classmate but tripping over her words in the process, Sakura admits to Nozaki that she’s always been a fan and that she wishes to stay by his side forever.

This earns Sakura an autograph (signed with a lady’s name, “Sakiko Yumeno”) and a spot as Nozaki’s assistant, because unbeknownst to Sakura and most of the rest of the world, Umetaro Nozaki is actually the author of a popular monthly girls’ romance comic entitled Let’s Fall in Love. Together Sakura and Nozaki embark on a relationship that is something more than friendship, something less than romance, and sometimes quite hilarious as artist and assistant attempt to navigate the challenges posed by high school life and serialized publication.

This earns Sakura an autograph (signed with a lady’s name, “Sakiko Yumeno”) and a spot as Nozaki’s assistant, because unbeknownst to Sakura and most of the rest of the world, Umetaro Nozaki is actually the author of a popular monthly girls’ romance comic entitled Let’s Fall in Love. Together Sakura and Nozaki embark on a relationship that is something more than friendship, something less than romance, and sometimes quite hilarious as artist and assistant attempt to navigate the challenges posed by high school life and serialized publication.

They’re not alone in this journey. Monthly Girls’ Nozaki-kun is full of characters quietly looking for love and pursuing their artistic dreams: there’s Mikoto Mikoshiba, aka Mikorin, the school heartthrob. There’s Yuzuki Seo, the “Lorelei” of the school’s glee club. There’s Yu Kashima, the “prince” of the drama club. There’s Hirotaka Wakamatsu, a basketball player who suffers from insomnia. And there’s Masayuki Hori, the drama club’s director and stage manager who moonlights drawing backgrounds for Let’s Fall in Love in exchange for Nozaki’s support as a scenario composer and script writer. Of course, none of these characters are quite as they appear to be at first blush, sometimes quite literally.

At its heart, Monthly Girls’ Nozaki-kun is all about the countless misconceptions and miscommunications that make life such a rich, messy, but ultimately rewarding experience. Reversal of expectations is at the center of every joke, and the punchline invariably results from when anticipation and perception don’t align with reality. For example, Sakura is initially attracted to Nozaki because he’s tall and athletic and projects an attitude that seems cool and aloof. But the inner person doesn’t quite match the outer appearance, because Nozaki is secretly a dedicated author of shojo manga. Nokazi’s apparent detachment is actually him scrutinizing the world around him for plot ideas, character concepts, and artistic reference material. Nozaki’s friend Mikoto Mikoshiba appears to be a confident, handsome playboy with a knack for charming girls with his words, but inside Mikoshiba is easily embarrassed, painfully shy, and desperate for the affirmation of his peers. Wakamatsu is so intimidated by wildcat tomboy Yuzuki Seo’s rough and violent demeanor on the basketball court that he mistakes her invitations to dinner, the movies, and the amusement park as acts of aggression. Routinely, characters envision exactly how a given scenario is going to play out, only to be proven drastically wrong. It’s in the disparity between idea and execution that comedy thrives.

But the discrepancy between perception and reality doesn’t just apply to the characters within the world of Monthly Girls’ Nozaki-kun. It also applies to the works of fiction within this fictitious universe, and that’s where the humor of the show gets meta-textual. As Dee Hogan points out in her short online essay “Heroine Boys and Princely Girls: How Nozaki-kun is Challenging Gender Roles in Fiction,” the original manga for Monthly Girls’ Nozaki-kun is subversive by its very nature because it’s a shonen manga with a female lead published in the shonen-oriented Gangan Online magazine. The subjects of this shonen manga are girls’ romance and the creation of shojo manga, both atypical material for comics aimed at young men. Within the series, Nozaki also bases his fictional characters on his real-life friends and classmates, only he switches the genders of various acquaintances to better match the expected archetypes of girls’ romance comics. For example, the bashful and self-conscious Mikoshiba serves as the template for Mamiko, the heroine of Let’s Fall in Love, while the rough-edged Yuzuki Seo becomes a bad boy rival love interest on the printed page.

On a thematic level, Monthly Girls’ Nozaki-kun has a lot to say about how we consume popular entertainment media, and how the comics that we read and the video games that we play shape our views of the world in subtle and often unrealistic ways given how rarely reality and fantasy coincide. Every stereotypical shojo romance situation that Nozaki and Chiyo explore in the course of their research—from riding two to a bicycle on the way home from school to sharing an umbrella on a rainy day—backfires in hilarious fashion. Mikoshiba’s investigations with dating games and bishojo figures fail spectacularly at preparing him to face his social anxieties. Characters frequently consult the Let’s Fall in Love manga to help them navigate the confusion of high school life. Inevitably they take away the wrong idea, the wrong life lesson, or the wrong strategy to deal with their current problem, such as when Kashima mistakes Hori’s artistic struggles for a desire to be treated like a princess.

Even if romantic comedy and a gentle subversion of gender roles aren’t your thing, you can still enjoy Monthly Girls’ Nozaki-kun for the perspective it gives on the creative process. I was surprised at how little I knew about the techniques that go into authoring manga, and Monthly Girls’ Nozaki-kun provides an entertaining introduction to the Japanese method of creating sequential art. I learned about beta inking, about applying screen tone, and about the importance of special effects artwork and backgrounds in establishing the proper mood and tenor for a scene. I also got a stronger impression of how proper editorial oversight can help a manga author flourish, while a lax and lazy editor can result in nothing but cartoons of inexplicable tanuki and equally improbable elephants. On a technical level, Monthly Girls’ Nozaki-kun is a treat. The color palette is bright and cheerful. The contrast of artistic styles between the show’s animation and the frequent cutaways to the Let’s Fall in Love shojo manga provide an interesting juxtaposition of visual styles. The music by Yukari Hashimoto is especially noteworthy. I haven’t encountered a score and a soundtrack that so seamlessly blend with an anime’s sense of comic timing since Masaki Kurihara’s work on Azumanga Daioh.

Originally broadcast on Japanese TV in 2014, Monthly Girls’ Nozaki-kun was also simulcast on Crunchyroll. It’s available on Blu-ray and DVD in North America through Sentai Filmworks. And if that’s not enough Nozaki in your life, the original manga by Izumi Tsubaki is being translated into English and released by Yen Press. I heartily recommend these releases, because Monthly Girls’ Nozaki-kun is a gem of a series, one that you can fall in love with over and over again.

![Lady Oscar: The Rose of Versailles [Anime Review] Lady Oscar: The Rose of Versailles [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/RoV_Vol2_Front_CoverArt_V1-480x360.jpg)

![SSSS.Dynazenon [Anime Review] SSSS.Dynazenon [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/16-9-SSSS.Dynazenon_Key_Visual_3.5-480x360.jpg)

![Back Arrow [Anime Review] Back Arrow [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/ba15-02686-480x360.jpg)

![Dawn of the Witch [Manga Review] Dawn of the Witch [Manga Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/16-9-DawnoftheWitch-cvr_02-480x360.jpg)