.jpg)

As I’m writing this, we are mere months away from the premiere of the live-action Hollywood adaptation of Ghost in the Shell. But before we get to the, ahem, Johansson-ization of Ghost in the Shell, let’s take a look at the anime and manga that predate and inform the live-action version.

Masamune Shirow’s manga started in 1989 in Young Magazine, known for publishing Katsuhiro Otomo’s challenging sci-fi works Domu and Akira. In it, Shirow presents a future world of cyborgs and cyber-brains in which human experience has been wholly digitized, resulting in a slew of new “cyber-crimes.” The tough, hotheaded Major Motoko Kusanagi commands an elite unit tasked with stopping them. Shirow’s original work falls victim to pedantic interludes explaining technical minutiae of his ambitious future world, but it also asks tough questions about the influence of technology and rampant capitalism on the lives of human beings.

.jpg)

Enter Oshii

Six years after the manga began, these questions would be reopened in a very different vision of Ghost in the Shell, from a very different creator. Director Mamoru Oshii took Shirow’s original, a pulpy police procedural, and refocused it, using powerful imagery of bloated cityscapes and cybernetic bodies to explore the meaning of identity and memory.

In the film, Motoko and her squadmates at Public Security Section 9 (a subset of the full squad from the manga) attempt to track down and put a stop to The Puppetmaster, a mysterious entity wanted for “ghost-hacking”: taking over people’s cyber-brains and using them to unknowingly commit crimes. As Motoko—far more mature and enigmatic than her manga counterpart—learns more about The Puppetmaster’s origins, she begins to question her own fully cybernetic body, and how much her appearance and even her memories really contribute to her identity.

.jpg)

It’s a movie defined largely by its negative space; shots with little to no movement or dialogue fill time between the detective work, making the whole thing feel eerily sterile and mechanical. When Oshii punctuates this with a now-famous scene of a rainstorm rolling in on the city, it feels like a blessed breath of fresh air—finally something that’s not under the technological thumb of humankind.

However, the film also features spectacular action sequences, including a climactic battle with a spider-tank (reportedly inspired in part by a real spider captured in a glass by animator Mitsuo Iso), but even when Oshii is indulging in less cerebral pursuits, his penchant for philosophy shines through; in one shot, the tank fires a barrage of bullets up a wall with an etching of the Tree of Life, stopping inches from the space marked “hominis”: human.

.jpg)

Finding Innocence

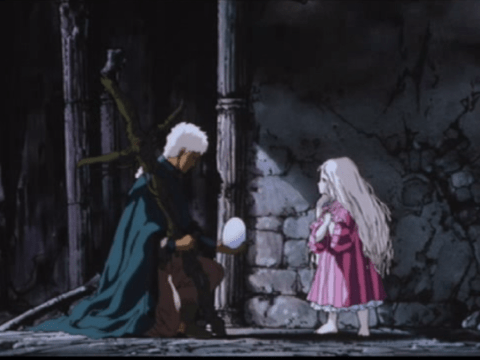

Oshii returned to the franchise almost a decade later, after the success of the 2002 TV series Ghost in the Shell: Stand-Alone Complex. Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence (2004), intended as a stand-alone film but a direct sequel nonetheless, sees Motoko’s persona fully merged into the global information network, leaving former squadmates Batou and Togusa to solve a series of murders alone.

Innocence lacks the first film’s clarity of purpose, in part because Oshii himself took over screenwriting duties from Kazunori Ito (Dirty Pair, the Patlabor movies), resulting in hardboiled detectives quoting Descartes and Milton in out-of-character philosophical soliloquies. It doesn’t help that, in contrast with the original’s pioneering compositing work, the CG in Innocence doesn’t meld well with the 2D animation, making scenes feel uncomfortably detached from reality.

.jpg)

Despite this, Oshii’s directing is arguably even more ambitious than in the first movie. The action scenes are carefully shot and choreographed but gut-wrenching all the same, and a quiet moment of respite at Batou’s apartment feels strangely true to life. Of course, freed from the constraints of negotiating with a writer, Oshii also includes his beloved basset hound as a constant presence. He’s even in most of the movie posters!

Ms. Kusanagi Goes

to Hollywood

Seemingly, Rupert Sanders’s live-action film is taking its cues from Oshii’s first film—not surprising, considering that Oshii’s vision of Section 9 was so powerful that it essentially became the franchise’s canonical one, overriding even Shirow’s. Unfortunately, casting Scarlett Johansson as The Major (note the lack of the Japanese “Motoko Kusanagi”) not only seems an odd choice for such an unflappable character, but it’s a slap in the face to Asian fans hoping to finally see more actors who look like them in lead roles.

What lessons will Sanders and his team take from the anime versions of Ghost in the Shell? Will they embrace an uncertain world of fallible memories and untrustworthy institutions? Or will they tell an arguably less compelling but simpler story of personal fulfillment? Will it have a basset hound in it? No matter what, the success or failure of the film will have big implications for the future of Hollywood adaptations of anime properties.