Director Masaaki Yuasa dives into the questions surrounding our very existence in Kaiba.

No viewer familiar with the works of Masaaki Yuasa could mistake the director’s preoccupation with the human body. Whether it’s a fascination with bodies in motion—of the long and lithe physique of the athletes in Ping Pong bending and stretching far beyond any human limit to emphasize their preternatural grace and ability—or with bodies in the throes of transformation—recall the orgiastic spectacles in Devilman Crybaby as mundane revelers warped into shapes simultaneously more grotesque yet revealing, or, more simply, the way the cast of Tatami Galaxy inflate as they eat, fly apart as their frustrations explode, fall to pieces after a tremor of disappointment—Yuasa’s works have long demonstrated an interest in the interplay between our physical forms and our sense of self.

Who could blame him? Our bodies are an endless source of vexation, afflicting us with illness, demanding constant maintenance from us, betraying us by projecting a false impression to others that obscures what we are certain is our true “self.” We try to remind ourselves that we are something more than the flesh we’re stuck in, that our mind is not defined by our appearance and body so much as limited by them, yet we know we cannot escape them. They are the medium by which we interact with the world and how it interacts with us. They are us, despite all the frustrations they breed, no matter how much we insist otherwise. It’s a dichotomy that’s tormented people since they developed self-awareness and flummoxed philosophers for centuries as they grabbed for language that seemed to always contradict itself. Animation, unrestrained as it is by the rigid laws of physics and biology, is then perfectly equipped to give voice to these frustrations, to express more literally those sensations, desires, and concerns that often feel so abstract to us or so impossible to describe to anyone else.

Existential Uncertainty

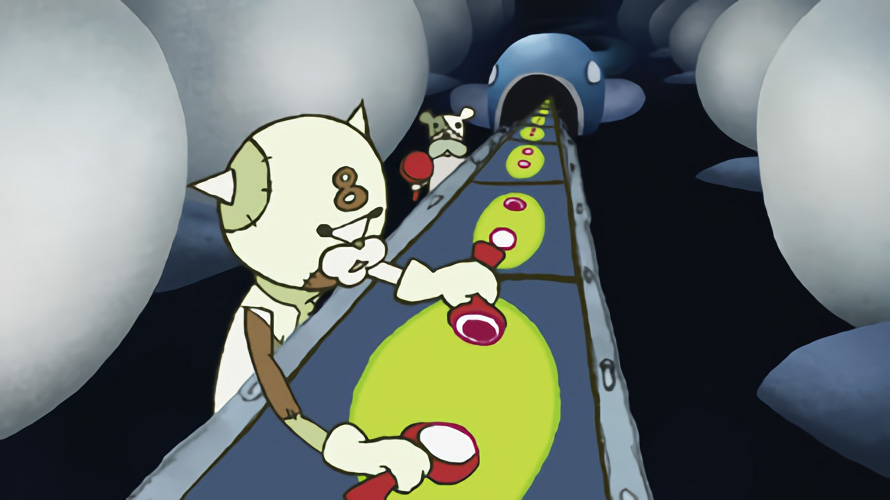

Kaiba, an earlier Yuasa production, is particularly attuned to these concerns. The story of an amnesiac young man sent fleeing on an odyssey to the far reaches of a galactic empire ruled over by the tyrannical and enigmatic Warp, it is simultaneously a more obtuse and yet more abstruse work than the majority of Yuasa’s later productions. For the characters of this world, their bodies are nothing set: technology has advanced to such a point that memories can be uploaded onto computer chips and swapped effortlessly (albeit for an astronomical price) between bodies, where memories persist even after death in the form of floating cosmic streams that coalescence and eventually gather in massive memory tanks erected across the empire.

Such developments bring with them an end to the old and unfortunate truth that our minds are defined by our flesh, and so the flesh in turn becomes a commodity as disposable as any other: year after year designers trot out ever more eccentric models like fashion houses trotting out this season’s haute couture; what bodies the ultrawealthy cannot obtain through cash they steal by employing hordes of mind-robbing robots and teams of body-swapping scavengers looking for a quick dollar and easy social advancement. Even the poor, disadvantaged as they are in this system, might at least trade their current “model” for the money that could help them or their loved ones realize other, more pressing desires. Why shouldn’t they, when every moment the world around them emphasizes the split between mind and body we all intuitively feel? What point is there in getting sentimental over what is effectively a costume only as valuable as it is useful?

Yet for all the freedoms such advances allow, they impose a variety of new limits, and with them a legion of questions not easily answered. What is death in a world where one’s memories linger forever and can be recalled—without one’s will—by a tourist pressing a button? When one can be summoned up out of death and placed into a new body against one’s will? When an accident might erase one’s memories while leaving one’s body intact? More pressingly, what is living in a world where the comfortable if constraining certainty of bodies no longer exists, where we no longer have the luxury of a set body to identify by? Where memories are so pliant that they can be rewritten on a whim, erased by a gun, or devoured by the legendary and titular plant that returns once every few millenia to unite all memories in existence into one gargantuan egoless mass? What is gender, what is sex when one can swap between male, female and bodies of uncertain character on a whim? What is a person—what is the self—when all the normal signifiers and boundaries that construct identity are made porous by technological advancement? How could we ever love or trust another when we could never again be certain of who they are from second to second? Of who we are?

For a while, Kaiba tackles such questions deftly, if didactically. The first half of the series consists of a series of interconnected parables that follow our amnesiac hero on a picaresque journey to the far-flung corners of Warp’s galactic empire. Though the simplistic, almost superflat art style and cosmic setting might as quickly suggest an oversexed and punky update of Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince and a debt to underground animation like Fantastic Planet, by its meditative tone, episodic structure, and focus on the interplay between body and identity it bears more in common with Galaxy Express 999.

In one instance Kaiba finds himself party to a dispute between siblings trying to raid their dying and seemingly senile grandmother’s memory for clues to the whereabouts of a lost treasure. In another he finds himself on the planet Abipa, center of the body fashion industry where dwells Patch, creator of the body-swapping method now turned gibbering prophet bent on revolution, and his lover, Quilt, who now resides in the body of a patchwork dog he’s assembled from various discarded pups over the years. Suggestions are present of a larger plot involving the terrorist organization The One Mind Society, but they’re secondary to the immediate interactions between the protagonist and the various bizarre worlds and eccentric characters he encounters on his travels, which are themselves little more than vehicles to explore the many thorny epistemological and existential questions that preoccupy Yuasa. These are slow-burning tales, meditative in mood, ambiguous about any of the conclusions they draw, and so almost uniformly melancholy: Yuasa may be eager to ask questions, but he is less interested in answering them than exploring their facets.

Full Steam Ahead

Sadly, Yuasa abandons this anthology approach near the halfway point to focus instead on the conflict between the terrorists and Warp, and in doing so abandons what distinguishes Kaiba. While it still trades in the themes and anxieties that made the earlier episodes so tantalizing, the mode of the telling is sadly more explosive, more dynamic; concepts and philosophical quandaries that were once the fertilizer used to tell challenging stories become now the nitrous necessary to move a breathless plot along to its apocalyptic conclusion as the story hurdles from hastily explained plot point to hastily explained plot point or from major double-cross to triple-cross to quadruple-cross. Characters are given more time, but the heaps of backstory piled on them only amount to so much telling; Yuasa is now in too much of hurry to make them seem like anything more than functionaries of the plot. There’s nothing inconclusive in this larger story as there was in the earlier vignettes; where those introductory tales traded in uncertainty, the major story arc ends up trading in wide-sweeping bromides about the power of love and forgiveness (both of others and of self) that seem too convenient because they are too certain. But it feels dishonest, as if schizophrenically opposed to the very principles it once defined itself by.

Yet the fact that it would separate so evenly down the middle into such disparate halves seems almost inevitable. So much of Kaiba’s greatest power stemmed from its ability to dwell on the inconclusive, after all, to bravely shy away from offering pat answers to intractable questions and from loaded endings that shanghaied audiences into specific feelings. After too long spent grappling with problems that couldn’t be pinned, it was almost as if Yuasa couldn’t help himself stumbling back to the tidy pleasures of plot. That would certainly explain why his works since have approached these same topics more stealthily. Similarly, we, after too long spent pondering the vagueries that constitute our own identity, might settle again and again into the tidy comforts of our mind-body dichotomy. We are not built to long question the systems that give us the illusion of continuity; why should the works we construct to examine the same be any less flawed?

Kaiba is available in a Blu-ray/DVD combo set from Discotek Media.

This story appears in the Spring 2018 issue of Anime USA Magazine. Click here to get a print copy.