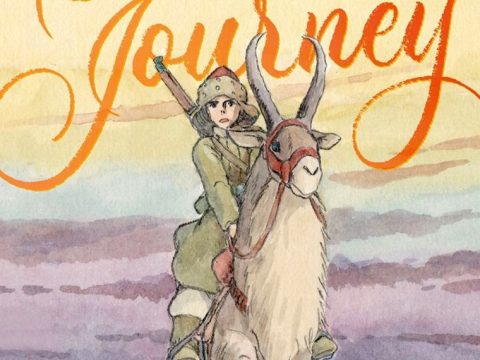

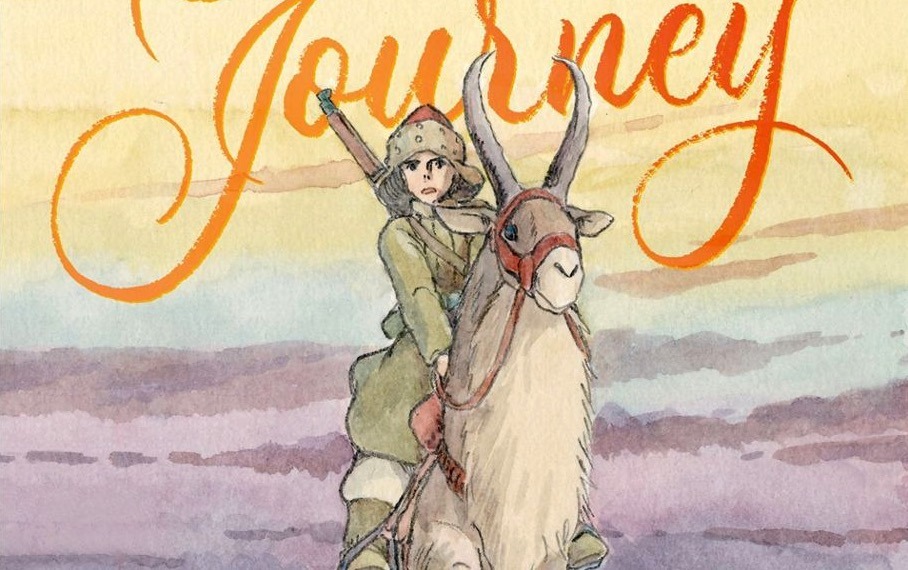

Hayao Miyazaki’s early work Shuna’s Journey finally received an English release, thanks to graphic novel publisher First Second Books. Alex Dudok de Wit, who has written a book about Grave of the Fireflies published by the British Film Institute, worked as the translator. He spoke with Otaku USA about his interest in Japanese cinema, the process for translating Shuna’s Journey, and Japanese movies he recommends.

How did you first get interested in Japanese cinema?

Through my parents, who are both interested in it too. I remember my father telling me about Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai and Ran when I was small. In the 1990s, when I was a child, we got hold of a pirated box set of Ghibli films, which hadn’t yet received legitimate releases in the UK. Even though the image quality and subtitles were terrible, I was fascinated by them, especially My Neighbor Totoro, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Porco Rosso.

How did you get involved in translating Shuna’s Journey? What was the process like for you?

I proposed the project to Ghibli in 2020. They kindly agreed—I was a little surprised that they did, as Shuna’s Journey had gone almost four decades without being translated! I then went about trying to find a publisher, naively sending emails to editors out of the blue. I quickly realized it would help to find an agent, so I asked Sylvain Coissard, an excellent French agent who specializes in graphic novels, and he set up the connection with First Second.

This process probably took longer than the actual translation, especially as the book doesn’t have a huge amount of text. That said, the translation wasn’t easy. The fact that there’s so little text made it all the more important to get each sentence just right—as did the fact that this is Miyazaki, and you don’t get to translate him every day! Luckily, I found the voice of my translation pretty quickly: the book is written in a kind of straightforward, timeless folk-tale narration. So the challenges were more around specific words and sentences.

What do you like best about Shuna’s Journey?

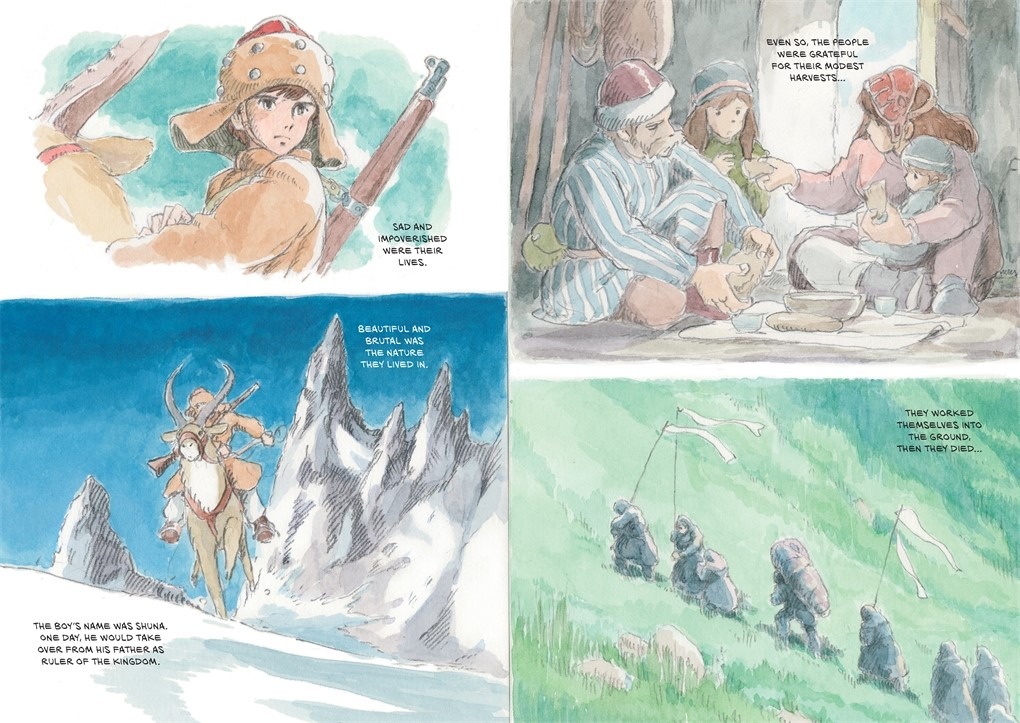

The mystery. Miyazaki often introduces surprising elements into his plots, not necessarily explaining them, but integrating them into the story in a way that makes some kind of intuitive sense. He does this a lot with Shuna’s Journey: the sea whose level rises and falls dramatically, for instance. This is the language of symbolism, of visual metaphor.

A recent article in The New Yorker made this point well: if Shuna’s Journey was a contemporary American blockbuster, it would be full of backstory and exposition. What was Shuna’s upbringing like? How did the slave trade arise? And so on. Miyazaki is happy to let you answer these questions for yourself, and that makes the story linger longer in the imagination. I think this is one reason why there isn’t much text in the book.

Please tell us about your book on Grave of the Fireflies.

It’s basically a collection of essays about Isao Takahata’s wartime masterpiece. I write about how the film was made—under tough conditions—at Ghibli, how it was received in Japan and abroad, and how it ties into the ways the war is remembered in Japan. But the book’s main part is devoted to a critical analysis of the film, with particular reference to the story it is based on and Takahata’s own public comments about the film and the war. Grave of the Fireflies is a much-loved work, but it isn’t talked about as much as some other Ghibli films (at least in the Anglophone world), which is why I wrote my book.

Do you have some favorite Japanese movies and Studio Ghibli movies you’d like to share?

Apart from Grave of the Fireflies, which is brilliant but tough to watch over and over (take it from me), my favorite Ghibli film is My Neighbor Totoro. The film was actually released in Japan in a double bill with Fireflies, and even though they are tonally very different, they actually have a fair bit in common. They both feature young siblings who are left mostly to their own devices (albeit in very different circumstances) and free to project their child’s sense of wonder onto their environment. One is about the pain of losing parents, the other about the fear of losing them, and in both cases this experience makes the older sibling mature beyond their years. And both films meticulously recreate a now-lost period of mid-century Japanese history.

Outside Ghibli, I love Yasujiro Ozu—the scene at the end of Late Spring where the father peels the apple is so powerful. Masaaki Yuasa, too: his approach to the medium of animation is so free, playful, and fun. Watching his latest feature INU-OH in a packed hall at Annecy Festival, with Yuasa sat in the front row, was one of my highlights of 2022.

Shuna no Tabi (Shuna’s Journey)Copyright © 1983 Studio GhibliAll rights reserved.First published in Japan by Tokuma Shoten Co., Ltd.

____

Danica Davidson is the author of the bestselling Manga Art for Beginners with artist Melanie Westin, plus its sequel, Manga Art for Everyone, and the first-of-its-kind manga chalk book Chalk Art Manga, both illustrated by professional Japanese mangaka Rena Saiya. Check out her other comics and books at www.danicadavidson.com.