“…unusually intelligent and challenging science fiction, aimed at smart audiences.”

The above quotation by Roger Ebert along with its “Two Thumbs Up” rating featured prominently on the VHS—and later, DVD—packaging, convinced a substantial amount of American cinema fans and casually interested “geeks” alike to watch Japanese animation in 1996, many of whom would be doing so for the very first time. Here was an audience that by and large had never read or even so much as heard of manga before in a context outside of the logo on the box that read “Manga Video” (contradictory, or self-explanatory?), and it was this audience which made the Japanese animated film number one on the Billboard Video charts; a feat rarely repeated in the years since. So it was that it became the most famous anime in the United States since the release of Akira roughly five years prior.

I speak not of Ninja Scroll—lest we forget, that had also been released around the same time period to significant commercial success, albeit without the critical acclaim—but the 1995 film Ghost in the Shell. Like so many other Japanese animated works, this was originally adapted from a Japanese comic book. Author Masamune Shirow, aware that his strengths lie as a conceptualist and that his manga scripts are absolutely un-filmable [and virtually unreadable…], gave director Mamoru Oshii permission to alter his work as much as needed for the sake of making the best film possible. Shirow’s setting dovetailed nicely with themes and concepts Oshii had explored throughout his previous works: a future world in which cybernetics are commonplace, the resulting digitalization of human thought rendering memories subject to manipulation, and a secret wing of the government known as “Section 9” being tasked with stopping such cyber-criminal acts via application of heavy armament. This particular brand of science fiction was not commonly explored at the time within the realms of anime or even live-action film. Besides this, there was Blade Runner and… other things that are not as awesome as Blade Runner, such as Strange Days and the highly entertaining yet not exactly intellectual Johnny Mnemonic. I’ll let the neckbeards argue incessantly over what is and is not “cyberpunk” because frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.

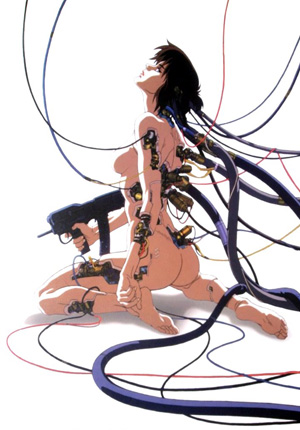

The first few minutes of Ghost in the Shell features a gunfight and explosive rounds applied to a human body courtesy of a woman who, at first glance, appears to be wearing no clothing. (Repeated rewinding, freeze-framing, and scrutiny revealed this not to be the case. It’s a skin-tight, flesh colored bodysuit.) There are no talking animals and nobody at any point breaks into song and dance. They may as well have put up a caption that read “Welcome to anime, ladies and gentlemen! Please incinerate all traces of Alan Menken before proceeding further.”

The first few minutes of Ghost in the Shell features a gunfight and explosive rounds applied to a human body courtesy of a woman who, at first glance, appears to be wearing no clothing. (Repeated rewinding, freeze-framing, and scrutiny revealed this not to be the case. It’s a skin-tight, flesh colored bodysuit.) There are no talking animals and nobody at any point breaks into song and dance. They may as well have put up a caption that read “Welcome to anime, ladies and gentlemen! Please incinerate all traces of Alan Menken before proceeding further.”

The woman is Section 9’s “Major” Motoko Kusanagi, and much like her male partner Batou she has a body that is nearly 100% cybernetic. This enables them to perform literally inhuman feats. As is commonplace in Oshii’s films, Ghost in the Shell focuses far more on investigation and personal introspection than action, though what action is present is spectacular and—for its time—groundbreaking. The investigation focuses on Section 9’s efforts to stop a master hacker known only as “the Puppet Master”; the introspection is adequately summed up by the film’s US advertising tagline “It found a voice… now it needs a body.”

The subject matter, art style, high-quality animation that continued the integration of CG with traditional cel-drawn animation as previously explored in Oshii’s Mobile Police Patlabor movies, musical score by Kenji Kawai, and a rather competently-produced English adaptation were all key contributors in making Ghost in the Shell accessible to US audiences. This earned Mamoru Oshii worldwide renown and formally cemented his positions as one of the top directors in the anime industry. James Cameron, director of the first two Terminator films, Aliens, Avatar, and still not Battle Angel Alita, famously described it as “a stunning work of speculative fiction, the first truly adult animation film to reach a level of literary and visual excellence.” Its green-laden visuals and action style was directly cited by the Wachowski Brothers as being one of the primary inspirations for the first installment of The Matrix. At the time, it felt like things had come full circle: anime and manga, which had developed several of its visual tropes and techniques from earlier American works, was now influencing American popular culture in very much the same way.

Sadly, this wouldn’t last. Animated feature films have become progressively rarer aside from yearly installments of children’s properties, and the noteworthy films of the last 5 years such as Sword of the Stranger and Summer Wars have been largely lost in the shuffle now that so many media options are available to consumers. With any luck, this can be overcome with cleverly-placed marketing and Manga Video’s impending release of Redline will gain traction beyond the “anime fans” segment of the population.

Ghost in the Shell ultimately ended up much more popular internationally than within Japan itself, and the film’s production was in part funded by Manga Entertainment in the first place. But the anime industry didn’t sufficiently capitalize on this international success. Other forms of entertainment media are far, far more efficient at taking advantage of fan interest before it subsides. If a Hollywood movie hits it big, the sequel generally comes out within two years or less. If a videogame is successful, follow-ups average within 2 to 3 years. If an American television show catches on, the new season starts within one year. But the next Ghost in the Shell anime project, Stand Alone Complex, would not be released until seven years later, and it took nine years for a theatrical sequel to Ghost in the Shell to see the light of day. By then the former innovations of Ghost in the Shell had become rote. All sorts of [post]cyberpunk hacker-oriented science fiction had been made, not just in anime but live-action film and videogames as well. By 2004 the Matrix sequels had effectively killed all mainstream interest. The world had moved on from where it once was, as did Mamoru Oshii, who hadn’t directed any anime projects in the interim.

As the rumors go, Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence was something Mamoru Oshii was “forced” to make in exchange for getting the go-ahead to work on more personal projects. Oshii is forever associated with Ghost in the Shell, but he’d much rather be known for his “Kerberos Saga” for which he’s made installments in virtually every medium there is. The fact that hardly anybody cares about the “Kerberos Saga” except for the aspects of it that Oshii didn’t directly create by himself no doubt eats him up inside, much like how I imagine it burns at Yoshiyuki Tomino that he’ll forever be known for his work on Mobile Suit Gundam instead of his “Byston Well” saga. Sure enough, his next project after Innocence was another inscrutable live-action Kerberos Saga film.

At the time Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence came out, it was largely panned by fans due to the fact that it felt like a step backwards compared to Stand Alone Complex. Audiences expected more given all the years of waiting and the fact that Innocence was the very first anime movie ever selected to compete for the Palme d’Or award at the Cannes International Film Festival. Further compounding matters was the lackluster US release: it was Japanese language only and the subtitles were terrible! Whether you preferred dubs or subtitles, you were out of luck. Eventually the film was dubbed into English for the UK, then dubbed into English again for the US using virtually the exact same cast and script as the first English dub. Yeah, I don’t know either, but after comparing the two I recommend the UK-produced dub.

The style of Innocence is completely removed from that of the original Ghost in the Shell. The action scenes were more stationary and the dominant color motif was changed from green to orange; Oshii later went back and re-did the original Ghost in the Shell to change everything to orange there, too. I guess when you reach a certain level of success, you no longer have to contend with others saying “no” to your ideas, which can lead to some highly questionable filming decisions. Longtime Star Wars fans know what I’m talking about. As I noted back in the February 2010 Otaku USA review of Ghost in the Shell 2.0, I imagine the change was brought about so as to either retroactively distance the film from the Matrix trilogy or tie it in with Oshii’s prior live-action film project, Avalon.

It’s either that or Oshii’s just plain gone crazy. I like The Sky Crawlers, but his most recent works are seriously testing my patience. The original Ghost in the Shell may have marked the start of the “modern-era” Mamoru Oshii, but come Innocence it seemed clear that he cared far more about showing audiences his basset hound than the characters, setting, or plot of the film itself. His basset hound has become a recurring one-off image throughout his movies, but that freaking dog is featured front and center on the Japanese cover to this film, because it ostensibly represents the titular “innocence.” Fellow Otaku USA correspondent Mike Toole once changed the caption to read “BASSET HOUND: THE MOVIE” in response. On top of that, Innocence focuses on yet another of Oshii’s real-life interests that he further developed in the interim following the original Ghost in the Shell: humanoid life-sized female sex dolls. Oshii is a leader of the “Doll Love” movement which advocates that such dolls aren’t merely a replacement for a real woman, they ARE the ideal woman. Fortunately for all of us, that is not the overt message of this particular movie. In Innocence, those dolls go berserk and kill their owners (literal death, as opposed to just the normal spiritual). Hans Bellmer would approve.

Rewatching Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence now that the buzz has subsided, I must admit: the movie’s actually enjoyable! The basset hound-ocity is largely limited to a few scenes, the dialogue isn’t nearly as pretentious as I remember it being, and the “entire conversations in which all people do is quote philosophers back and forth to one another” was a false memory. Implanted in my head by hackers, perhaps? Or am I just beaten down at this point? The dialogue is still rather “heady,” but it’s no more or less so than Stand Alone Complex and there’s good reason for it to be that way, as I noted in the August 2011 issue of Otaku USA. The main character focus for this film switches to Batou, as the presence of “the Major” is largely absent as a result of events in the original film. I don’t mind this, as several of my favorite Ghost in the Shell stories are ones in which Kusanagi isn’t the central character anyway. The Mamoru Oshii theatrical incarnations of Ghost in the Shell may not have any continuity tie-ins to the Stand Alone Complex titles, but it’s a good story for fans of Batou, that not-so Laputan Machine, all the same. The proper time for a Ghost in the Shell sequel would have been between 1999 and 2002; had this exact same movie come out then, I think it would be less maligned than it is.

Rewatching Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence now that the buzz has subsided, I must admit: the movie’s actually enjoyable! The basset hound-ocity is largely limited to a few scenes, the dialogue isn’t nearly as pretentious as I remember it being, and the “entire conversations in which all people do is quote philosophers back and forth to one another” was a false memory. Implanted in my head by hackers, perhaps? Or am I just beaten down at this point? The dialogue is still rather “heady,” but it’s no more or less so than Stand Alone Complex and there’s good reason for it to be that way, as I noted in the August 2011 issue of Otaku USA. The main character focus for this film switches to Batou, as the presence of “the Major” is largely absent as a result of events in the original film. I don’t mind this, as several of my favorite Ghost in the Shell stories are ones in which Kusanagi isn’t the central character anyway. The Mamoru Oshii theatrical incarnations of Ghost in the Shell may not have any continuity tie-ins to the Stand Alone Complex titles, but it’s a good story for fans of Batou, that not-so Laputan Machine, all the same. The proper time for a Ghost in the Shell sequel would have been between 1999 and 2002; had this exact same movie come out then, I think it would be less maligned than it is.

I never would have even heard of Ghost in the Shell were it not for Mamoru Oshii’s original movie. The success of that film helped pave the way for anime to be recognized as a viable commercial entity in the United States at the major retailer level, and while those glory days are a thing of the past, anime still occupies at least a tiny section within most stores that still actually sell movies. And despite its age, you’re likely to spot Ghost in the Shell as one of the few titles there on the shelf. Its influence upon anime and Hollywood was undeniable for its time, which is what makes the relative lack of similar material so utterly confounding. I can only conclude that anime-viewing audiences in Japan simply don’t seem to want to see this sort of thing given its repeatedly poor receptions there. I hear from many fans in Japan that “the majority” of anime fans there are just as confounded by the narrative-espousing “iyashi-kei” phenomenon as I am, but if that really is true then why don’t they support the antithesis of such material when it does come out? If they’re right, then why is it so difficult to get animation projects such as this made in the first place such that the only time anyone ever makes Ghost in the Shell is through international financing? Perhaps the only solution is for anime to follow the Puppet Master’s advice and redefine its identity: to no longer be quite what it was in the 80s, 90s, or 00s but a combination of them all that incorporates their strongest traits to ensure maximum survivability. I wonder where it’d go then? The net is vast and infinite.

Ghost in the Shell © 1995 Masamune Shirow/Kodansha Ltd./ Bandai Visual Co., Ltd,/Manga Entertainment

Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence © 2004 Dreamworks, LLC

Related Stories:

– More Than Ghost In The Shell: The Legacy of Masamune Shirow

– Ghost in the Shell ARISE: Ghost Pain review

– Stray Dog Of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii Review

– Ghost in the Shell Movie Planned for 2015

– Margot Robbie May Star in Spielberg-Backed Ghost in the Shell Live-Action