Wolf Children is Mamoru Hosoda’s third full-length feature (and the third to premiere in the U.S. at the New York International Children’s Film Festival) and it continues his streak of artistically superior works of animation that also happen to be real crowd-pleasers. As good as The Girl Who Leapt Through Time and Summer Wars are, Wolf Children is the richer, more emotionally mature work of the three. Its main focus is on three characters, a mother and her two children, representing quite a change from the large casts of his previous films, and it explores the nuances of their relationship as the mother raises them on her own in an isolated setting, initially trying to shield them from human society and then trying to help them assimilate. The setting is the mountainous region of Toyama Prefecture and it recalls the lush, natural forest backgrounds of My Neighbor Totoro and Princess Mononoke, going so far as to include a massive tree like the camphor tree housing Totoro and a host of wildlife species like we saw in Mononoke, including a fox, some bears, and a wild boar. It all adds up to a moving, supremely satisfying dramatic story of growth, change and adaptation, themes central to many important works of anime.

The central character is Hana, a female college student, who meets a mysterious boy who sits in her class but is not enrolled in the school. He works for a moving company and the two soon become romantically involved, even after he reveals that he’s a mixture of wolf and human and transforms into a wolf right in front of her on a cold, starry night. She gets pregnant—twice—after which he disappears, only to turn up as a wolf corpse in a canal. Now alone, Hana struggles to hide the fact of her part-wolf children from her landlord and neighbors in the apartment complex (who can hear them howling) and a suspicious Child Welfare Agency, before she is finally forced to seek shelter far from prying eyes. It’s not clear how she manages it, but she finds a ramshackle house (“virtually rent-free”) in a farming region in the mountains and resolves to fix it up and live there, attempting to grow her own vegetables and letting the two children, a girl, Yuki, and a boy, Ame, run as wolves in the forest. (Yuki often comes back with all sorts of animals she’s captured.) Gradually, Hana accepts advice from her neighbors and succeeds at farming and tries to acclimate her children to other people, enrolling them in school and getting a job for herself as a wildlife ranger.

As the first half of the film followed the struggle of Hana to care for and protect her children and create a stable home, the dramatic focus then shifts to the two children and the establishment of their identities and how they adjust to being part wolf and part human. Yuki had been more aggressive and wolf-like since early childhood, while Ame had been more sensitive and human-like and much more fearful of his wolf side. After they reach school age, however, Yuki becomes more concerned about what her classmates think and says things like, “I made up my mind to behave as demurely as I can” and “I don’t want people to think I’m weird.” She develops a friendship with a new student, Sohei, a boy who seems to pick up on her true nature (“You smell like an animal”). More and more, she wants to fit in. Ame, on the other hand, after a harrowing incident where he’d finally let his wolf nature fully flourish and almost drowned in the process while trying to catch a kingfisher, comes out stronger as a result and decides to follow his instincts and run through the forest and connect with the animals, taking on a fox as a mentor. It all culminates in a lengthy storm sequence that decides the fate of all three family members.

The children often transform from human to wolf form quite suddenly and unexpectedly. Early on, a hungry little Yuki demands food and runs around their cramped apartment, soon running on all fours, with a wolf snout and wolf ears sprouting. They sometimes do this when they’re outside, which is why Hana tries to shield them from others and eventually has to train them not to do it. When they shift form while running, it reminds me of the way the Tanuki characters in Isao Takahata’s Pom Poko (1994) would transform from cartoon characters standing upright with distinctive features and clothing accessories to realistic-looking raccoon dogs running through the meadows in the forest. There is one beautiful sequence here where the family, experiencing their first winter in the mountains, runs out into the new snow, with the kids happily shedding their clothes and transforming into wolves and running at top speed through the snow and past the trees, with the camera following them at a furious pace, while poor Hana struggles to keep up.

There is a great deal of attention paid to the characters’ relationship to the land and the soil. One whole section documents Hana’s attempts to farm the land with her early efforts failing until advice and seed potatoes from neighbors, including the gruff Grandpa Nirasaki, enable her to succeed. This section reminded me of the farming sequences from Isao Takahata’s unsung Studio Ghibli masterpiece, Only Yesterday (1991), in which the young farmer, Toshio, guides city girl Taeko through her summer on a safflower farm. Later on in Wolf Children, we follow Ame as he explores the farthest reaches of the forest, a region where, it is said, the animals drove the humans away and one which, ultimately, Ame decides to call home. The scenes where he goes deep into the forest specifically recall similar scenes in Princess Mononoke.

One curious omission is that of modern technology. We never see a cell phone, TV set or computer. If it wasn’t for the late-model SUV that Hana drives late in the film, I’d assume this was set in an earlier time period. Director Hosoda has said that after the immersion in then up-to-date technology in his previous film, Summer Wars, he wanted to do something simpler and timeless.

If I have any small complaint, it’s that the children don’t age during one crucial section after they move to the farmhouse in the mountains. The children are five and four, respectively, when they get there, yet they don’t visibly grow at all for the next several scenes, despite the fact that time is shown passing with the changing of seasons and the failures of Hana’s earliest crops. At least a year goes by, maybe longer, yet they look the same that whole time. They don’t start aging until they begin school, with Yuki entering first grade and Ame following her the next year, followed by a clever montage showing them passing through the next several grades.

The voice cast is led by Aoi Miyazaki, a popular model and actress who is best known to fans in the west for her portrayal of the title role in Nana (2005), the first live-action film based on Ai Yazawa’s famous manga. She plays Hana and does a superb job at capturing the varied emotional states the character goes through, from shy college girl to protective mountain mama and all points in between. Also in the cast is legendary film actor Bunta Sugawara, famed for starring in dozens of yakuza movies in the 1960s and 70s. Here he plays Grandpa Nirasaki and boasts a spectacularly gruff voice. (Sugawara’s frequent co-star in yakuza movies, Junko Fuji, did the voice of Granny in Hosoda’s previous film, Summer Wars.) Megumi Hayashibara, who may be the most well-known and popular of Japanese voice actresses, turns up in Wolf Children in a supporting role as Sohei’s mother.

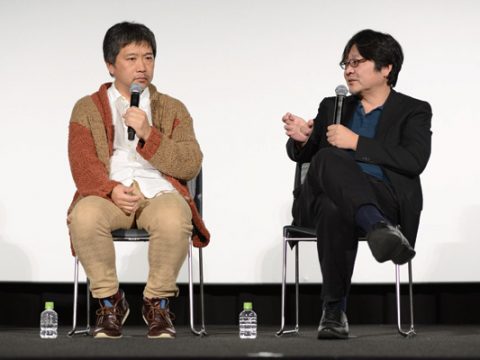

Despite the fantastic elements, the characters in Wolf Children are all very realistically drawn and the backgrounds designed and animated with as strong a sense of place as we get from the best Ghibli films, including the ones cited above. The three main characters are quite strongly etched and keep us engaged throughout a dramatic tale that spans 13 years (and 117 minutes). It ran in a Japanese-language, English-subtitled print, shown on 35mm film, at the New York International Children’s Film Festival on March 9, 2013, and the audience, a sold-out crowd of parents, children, teens and adolescents, was quiet and attentive throughout, laughing at the film’s bursts of humor where appropriate. Director Hosoda was in attendance and answered questions after the movie and then sat in the theater lobby to sign posters and draw characters for hundreds of appreciative fans, young and old.

Don’t miss our exclusive interview with Mamoru Hosoda from NYICF, as well as our transcript of his Q&A session. For an alternate take on Wolf Children, you can read Matt Schley’s review as well. For more NYICF, see our report on NYICF 2010, where Mamoru Hosoda’s Summer Wars premiered.