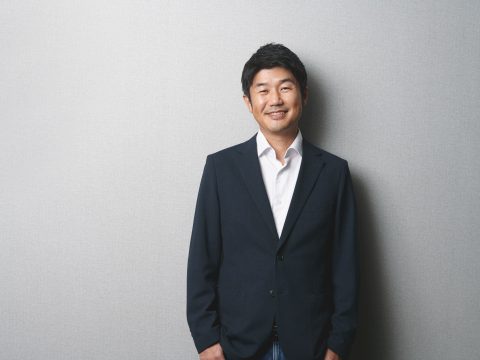

It’s quite possible you wouldn’t be reading this website without Frederik L. Schodt.

It’s quite possible you wouldn’t be reading this website without Frederik L. Schodt.

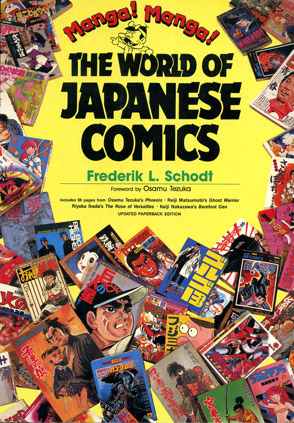

It’s hard to overstate the impact the writer, translator and interpreter has had on western anime and manga fandom. Writing about manga before anybody in the States was even eating sushi, Schodt published a book titled Manga! Manga! in 1983, giving the U.S. its first glimpse of this whole “Japanese comics” thing.

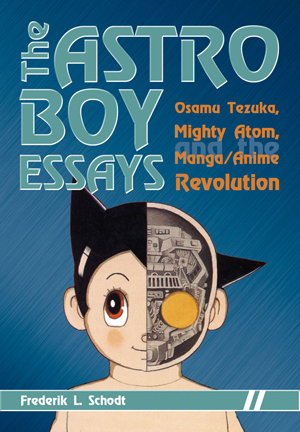

Since then he’s continued to write about Japanese pop culture, with books about Astro Boy, Japanese robots, and most recently, the Japanese circus of the 1800s. He was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun by the Emperor of Japan in 2009. Basically, he’s a big deal.

We sat down with Schodt at Otakon Vegas and talked Japan! Japan!

So you have a new book (Professor Risley and the Imperial Japanese Troupe) out this year.

Yeah, it’s a big deal.

How has the reception been?

It was nice, because it won an award from the Circus Historical Society. So that was a lot of fun for me.

How did you get interested in the topic in the first place?

I first heard about the Imperial Japanese Troupe through some books published in Japan. And then in reading one of them, I first heard about Professor Risley, the guy who put together the troupe, and I’d never heard about this guy, or the troupe either.

I tend to like people who fall through the cracks of history, who’ve done extraordinary things related to Japan and America. I just thought, “this is fascinating… why haven’t I heard of this guy?”

Professor Risley and the Imperial Japanese Troupe still aren’t very well known, but like other figures I’ve written about, whether it’s Astro Boy or Tezuka or whatever, I’m on kind of a mission to make people more aware, not only of Professor Risley, but of how very early popular culture exchanges were going on between Japan and the west.

You first went to Japan in the mid-sixties…

You first went to Japan in the mid-sixties…

Yeah, 1965. It was another world.

That’s what I wanted to ask… it had to be just a completely different place.

Totally different. In the talk I gave earlier about Astro Boy, somebody asked an interesting question about how [Osamu] Tezuka would’ve seen today. The thing that’s always fascinated me about Astro Boy is that Tezuka created the story in 1951, and he was envisioning our now. Astro Boy, in the story, is born on April 7th, 2003, so it’s really our now.

It’s so fascinating, because Tezuka was in such a different environment. This was six years after World War II. They were just digging out of the ashes, basically, and here he was trying to imagine what the world might be like in our period. Even though it’s a story for children, it’s interesting to try to correlate the predictions he was making. He talks about things like suicide bombers, artificial intelligence, discrimination against other races and machines, and things like that. There’s a lot that relates to today.

Even when I went to Japan in ’65, which was 14 years after Tezuka came up with Astro Boy’s story, Japan wasn’t the country it is now at all. People were still trying to pursue development. They weren’t thinking about ecology, there was terrible pollution, it was a totally different environment.

How do you think that compares to today, where it seems a lot of people are playing up how Japan’s on a downslope compared to China or Korea?

Japan’s obviously been going through a really tough situation, and probably will continue to for a while. But there are some really important things going on in Japan that people are overlooking. I think Japan is still capable of doing some amazing things and making amazing contributions.

On the other side of this, we have a lot to learn from what they’re going through now, because we’re all going to go through that. For me, the biggest change that’s happened in the last 20 years in Japan isn’t the economic recession, it’s that the population pyramid has flipped. That’s had implications that people never imagined. They’re huge.

And if you think they’re big in Japan, just wait to see what happens in China when the one-child policy starts to really kick in. They’re relaxing it now, but the effect of the one-child policy in China will probably be even more dramatic than in Japan. And without immigration, we’d see it in the U.S. too. So there’s a lot of learn from Japan.

What about these Cool Japan initiatives? Some people think they’re a joke, others think they’ll have a big impact…

It’s interesting to see how the government has become involved in this initiative. On one hand, you might consider government involvement in something that’s supposed to be cool kind of the death of cool. But maybe right now the animation industry does need a little help.

There are a couple risks, of course. One is that by investing in cool, you can kill cool really easily. And in Japan, manga and anime aren’t necessarily what the government like to have representing Japan. It’s a double-edged sword. You’re investing in cool, but not necessarily in things that might lead to a better image of Japan. Animation, and especially comics, have kind of an underground quality, you know? They have their animal spirits. So it’s kind of like a wild horse. You want him to go one direction, and maybe he will, but maybe he won’t. So that’s the risk they take.

When our generation was getting into manga, we had guides like your book Manga! Manga!, but how did you discover manga?

I first became aware of manga around 1970, because I went to a Japanese university. All my friends were reading manga, and at that point manga had become sort of like rock and roll in the United States: sort of a badge of counter-culture. It was actually one of the most creative times in manga. I lived in a dorm, and all my friends and roommates were reading manga all the time, instead of studying. That’s when I became really hooked.

When I was in my later 20s, I formed a group with a group of friends to translate manga.

That group’s plan was to translate Tezuka’s Phoenix first, right?

We did translate Phoenix. We didn’t know what we were doing, because no one we knew of had translated stuff before. We wanted to just translate something, show it to the world, and hopefully publish it. We were way too early, so we couldn’t get anything published, but we did go to Tezuka and ask if we could translate Phoenix. We somehow got in, and Tezuka liked us. We also did some stuff by Leiji Matsumoto which was never published.

We did the first five volumes of Phoenix, and that collected dust in Tezuka’s safe for 25 years, until it was finally issued by Viz. And then we were finally commissioned by Viz to finish the remaining volumes.

So there’s a 25-year gap between translating volumes five and six?

That’s right. At least 25.

You’ve done so much work with Tezuka. What keeps bringing you back to him?

Tezuka just had an amazing influence on me. I think he was a genius. I mean, people say that kind of thing all the time, but I think he was a real genius. I never met anybody like him in my life. I worked as his interpreter when he would come to America, and we toured around Canada and the States a couple of times.

Something that’s fascinating about Tezuka and Astro Boy is that he created the entire framework for the anime and manga industry with that one work. You have a manga, you animate it into a 30-minute TV series, you create merchandise, you create feature films, then you keep drawing it and create this Godzilla machine… that’s where it all comes from.

He didn’t just create these amazing works, he also created this whole thing that all of us are indebted to.