From now until the end of the year, Otaku USA e-News presents 98 Degrees: a deep dive straight into the anime of 1998. Which greats of ’98 would you like to see covered? Comment below or drop our editor a line.

From now until the end of the year, Otaku USA e-News presents 98 Degrees: a deep dive straight into the anime of 1998. Which greats of ’98 would you like to see covered? Comment below or drop our editor a line.

Adapted from a long-running shonen manga by writer Hiroshi Takashige and artist Ryoji Minagawa, Hirotsugu Kawasaki’s film Spriggan hit theaters when big-budget, sci-fi action anime flicks were all the rage and, arguably, the torchbearers of anime in the west. Kicked off with the release of Akira in 1988 and peaking with the release of the east/west co-production Ghost in the Shell in 1995, the theatrical action sci-fi genre featured trademarks like hyperkinetic action, vaguely-realistic character designs, richly-detailed backgrounds, vague stabs at spirituality, and all-important computer-generated sequences peppered in for good measure.

With Katsuhiro Otomo (creator and director of the aforementioned Akira) attached in a supervisory role, there were expectations that Spriggan could be the next Big Deal.

It wasn’t.

Not that it didn’t have potential, though. Deftly animated by Studio 4℃ (Mind Game, Tekkonkinkreet), the casual observer could be easily fooled into thinking they were watching a film by Production I.G—and in the late ‘90s, that was about as high a compliment as you could give. Best known for their work with Mamoru Oshii, every iteration of the Ghost in the Shell franchise, and the new FLCL sequels, Production I.G helped define the look of theatrical anime in the ‘90s —or at least how it was perceived over on the English-speaking side of the world.

Not that it didn’t have potential, though. Deftly animated by Studio 4℃ (Mind Game, Tekkonkinkreet), the casual observer could be easily fooled into thinking they were watching a film by Production I.G—and in the late ‘90s, that was about as high a compliment as you could give. Best known for their work with Mamoru Oshii, every iteration of the Ghost in the Shell franchise, and the new FLCL sequels, Production I.G helped define the look of theatrical anime in the ‘90s —or at least how it was perceived over on the English-speaking side of the world.

In any case, the inspiration was clear. The workmanship of 4℃’s animators is still impressive twenty years later—doubly so because prior to Spriggan, it had earned few accolades outside of its work on Memories (1995), another high-brow Otomo film, despite being founded in 1986. While the studio’s best-known work was ahead of it (they’d later work on the anthology film Genius Partyand international co-productions like The Animatrix, First Squad, and Halo Legends), it’s impossible to fault Spriggan for its ambition.

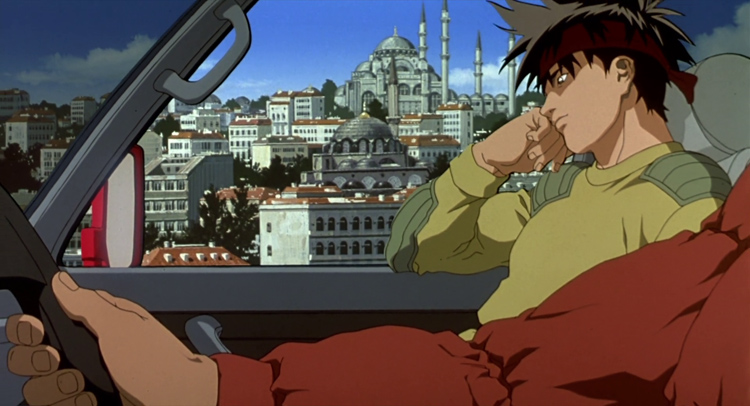

The film’s protagonist, a high school student-slash-secret soldiernamed Yu, gets caught up in a global conspiracy that begins with researchers discovering Noah’s Ark. From the frozen caves of Mount Ararat, the film jumps to a battle in an unnamed jungle, then to a Japanese high school, to a cyberpunk downtown high-rise, and then back to Turkey for the film’s second and third acts. Throughout it all, each location is lavishly-detailed and well-rendered. The soundtrack by Kuniaki Haishima exhibits Hollywood-like aspirations, with Hans Zimmerman-esque orchestral scores, chanting, and instruments that invoke the film’s exotic settings.

The film’s protagonist, a high school student-slash-secret soldiernamed Yu, gets caught up in a global conspiracy that begins with researchers discovering Noah’s Ark. From the frozen caves of Mount Ararat, the film jumps to a battle in an unnamed jungle, then to a Japanese high school, to a cyberpunk downtown high-rise, and then back to Turkey for the film’s second and third acts. Throughout it all, each location is lavishly-detailed and well-rendered. The soundtrack by Kuniaki Haishima exhibits Hollywood-like aspirations, with Hans Zimmerman-esque orchestral scores, chanting, and instruments that invoke the film’s exotic settings.

A fight through the covered markets of Istanbul looks like it could have been pulled from any of the Bourne movies, and the film’s globetrotting style is a bit like Indiana Jones meets James Bond by way of animated Japanese cyberpunk. The assortment of augmented super soldiers and psychics might remind viewers of the Metal Gear Solid series, too.

The film certainly drew some strong inspiration from proven formulas—but, unfortunately, it falls flat on its face in the second half. A seemingly never-ending parade of new characters, extraneous expository dialogue and all too familiar clichés (religious imagery, weather control devices, and super soldier programs, to name a few) makes the film drag once it progresses past the fast n’ furious action of the first act. These issues might be symptomatic of adapting a long-running comic into a single film—or perhaps it just needed a judicious script editor—but whatever the reason, its second half is a slog.

Not that there aren’t moments of action and comedic brilliance. In one scene featuring a shootout at a snow-covered research station, an enormous cyborg named Fat Man (with a Gatling gun for an arm) opens fire on Yu. Dodging his gunfire, Yu leaps behind a storage building only to emerge a moment later in the back of a driverless jeep, returning fire with the vehicle’s mounted gun. Despite the lack of a driver, Yu’s jeep deftly swerves around the battlefield as he avoids getting shot.

Not that there aren’t moments of action and comedic brilliance. In one scene featuring a shootout at a snow-covered research station, an enormous cyborg named Fat Man (with a Gatling gun for an arm) opens fire on Yu. Dodging his gunfire, Yu leaps behind a storage building only to emerge a moment later in the back of a driverless jeep, returning fire with the vehicle’s mounted gun. Despite the lack of a driver, Yu’s jeep deftly swerves around the battlefield as he avoids getting shot.

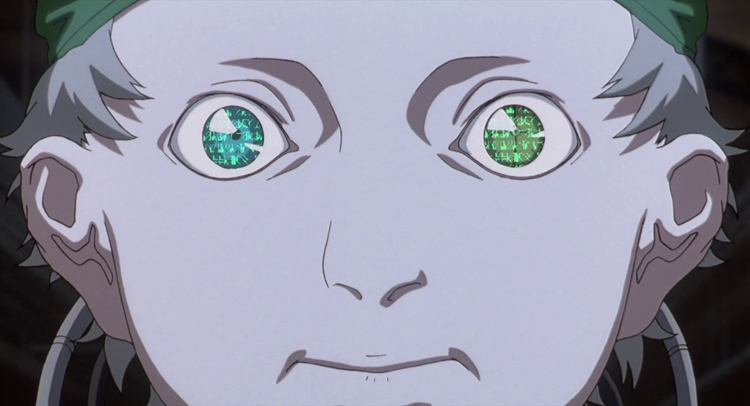

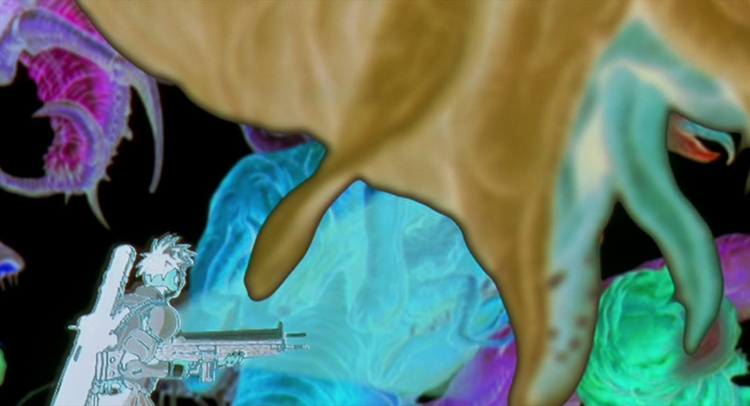

Had the film offered up more stupid action by talented animators, it would be easier to recommend. However, kinetic action gives way to “story’ by way of excessive expository dialogue—and an alarming number of scenes featuring computer graphics and compositing that haven’t held up well over the past two decades. While Production I.G’s Ghost in the Shell and Patlabor films used early computer graphics to represent actual computer systems, Spriggan’s animators made the mistake of trying to use it to represent the surreal interior of Noah’s Ark. Looking back, it’s clear the technology wasn’t quite there yet.

As a high-budget sci-fi action thriller, Spriggan was in the right place at the right time, and, with Otomo involved, seemed poised to become yet another legendary film. Unfortunately, rather than making waves, Spriggan landed with a dull thud. Had the film followed through on the globetrotting near-future sci-fi feel of the film’s first half, I suspect that viewers would have walked away happier.

As a high-budget sci-fi action thriller, Spriggan was in the right place at the right time, and, with Otomo involved, seemed poised to become yet another legendary film. Unfortunately, rather than making waves, Spriggan landed with a dull thud. Had the film followed through on the globetrotting near-future sci-fi feel of the film’s first half, I suspect that viewers would have walked away happier.

While contemporary big-budget anime thrillers continue to be celebrated decades later, Spriggan is a mostly forgotten oddity from an era when anime’s strongest selling point was that it wasn’t “kids’ stuff.” Spriggan, though, is an adolescent effort.

Sean O’Mara is the founder of Zimmerit and a frequent Otaku USA contributor.