With his latest film, Tetsuo: The Bullet Man, raking in an assortment of mixed criticism—an example of which you can find in the latest issue (June 2011) of Otaku USA—there’s no better time than the present to look back at the works of the mighty Shinya Tsukamoto.

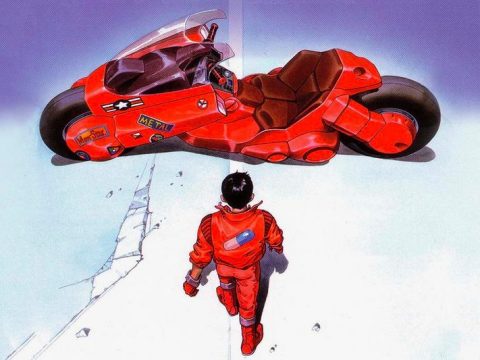

One of my greatest lamentations about modern day society—second only to the lack of effort required of you tech-savvy kiddos when it comes to finding porn—is that a budding film buff’s first brush with Tsukamoto’s inimitable Tetsuo: The Iron Man isn’t likely to be by way of a crusty VHS tape. Tetsuo, originally released in 1988, is weird, subversive and, in the eyes of someone that may just now be duly “shocked” by the world of Japanese cinema, it holds an elusive, dangerous quality.

Not that I want to bog this down with wistful, seemingly condescending those-were-the-days reminiscences; it just seems the ideal way to be introduced to a very unique body of work. I remember (here we go again) hanging out at a friend’s house when someone decided to bust out a double feature of strange and sordid cinema. First it was Peter Jackson’s Dead Alive (AKA Braindead), and if that didn’t leave us just that—in the best way possible, of course—the following act was none other than Tetsuo.

Not that I want to bog this down with wistful, seemingly condescending those-were-the-days reminiscences; it just seems the ideal way to be introduced to a very unique body of work. I remember (here we go again) hanging out at a friend’s house when someone decided to bust out a double feature of strange and sordid cinema. First it was Peter Jackson’s Dead Alive (AKA Braindead), and if that didn’t leave us just that—in the best way possible, of course—the following act was none other than Tetsuo.

Tetsuo‘s wildly DIY cyberpunk aesthetic has inspired quite a few imitators to this day, and some of its own inspirations can be found in the likes of Sogo Ishii, who directed the punk rock biker flick Burst City in 1982. In a somewhat cyclical way, Ishii’s own 2001 short, Electric Dragon 80,000 V, contains in it echoes of Tsukamoto’s work, if only because of its monochromatic look and manic, off-the-rails editing. Tsukamoto is far from a one-trick pony, though, and potential fans digging for diversity in his oeuvre have a bevy of treats awaiting them.

Hiruko the Goblin (1991) is almost completely straightforward and visually dull by comparison, but still ranks fairly high on the weirdo scale when placed next to more typical J-horror fare. The following year, Tsukamoto unintentionally illustrated the potential woes of adding to the mythos of one’s defining work in Tetsuo II: Body Hammer. It’s not so much the drastic shift in visuals—shot in 35mm and in color—that break it down as a film, but the story itself. The Iron Man is a curios specifically because its such an intangible oddity; adding to that with anything even resembling coherency serves, oddly enough, to dilute the concept as a whole.

From there you won’t find two of his films that are similar to one another in any significant way outside of recurring thematic elements. Tokyo Fist presents the seemingly grounded tale of a salesman’s torn relationship that leads to torn faces in the boxing ring. Placid waters roar by way of Tsukamoto’s keen eye and post work that drives home the skull-splitting, visceral nature of both the subject and the emotions bubbling beneath it all like veins full to bursting.

Tsukamoto plays the lead in that film; not as strange a position as one would normally assume. His presence in front of the camera can be just as memorable as behind, given the proper circumstances. You’ll find him in some form in pretty much all of his films, as well as those of his contemporaries. Who could forget his role, for instance, as the cleverly concealed hulk Jijii in Takashi Miike’s Ichi the Killer?

It’s often tempting, at first glance, to take a creator as visually singular as Tsukamoto and file him away in some overflowing style-over-substance waste bin, but there’s a very meticulous method to his madness. I believe it’s Tom Mes’s comprehensive 2005 book on the man, Iron Man: The Cinema of Shinya Tsukamoto, that contains an anecdote from Takashi Miike regarding Tsukamoto’s process. The two were filming different projects in the same studio at the time, and Miike recalled witnessing Tsukamoto setting up a shot at the start of the day. Miike went on to bang out a handful of scenes in devilishly speedy fashion, and when it came time to call the day a wrap, what did he see? Tsukamoto working on that very same shot; a perfectionist through and through. One can see the result of this painstaking precision in the likes of Gemini and Vital (the latter of which very well may have been the film he was working on at the time).

Of course, there’s much more to Shinya Tsukamoto’s filmography than we even have time to mention here, some of it more difficult to get a hold of than the rest. The truly dedicated can probably even track down his earliest work—dating back to super-8 shorts filmed in the ’70s—like 1987’s Denchu Kozo no Boken (The Adventures of Electric Rod Boy), which centers on a boy with a large electricity pylon protruding from his back and features some of Tsukamoto’s soon-to-be trademark stylings. Heck, maybe you’ll even be fortunate to find someone else’s lost relic lying around—an unlabeled video cassette containing within it a reel of wobbly, almost irreparably worn tape primed to spark an obsession.

Of course, there’s much more to Shinya Tsukamoto’s filmography than we even have time to mention here, some of it more difficult to get a hold of than the rest. The truly dedicated can probably even track down his earliest work—dating back to super-8 shorts filmed in the ’70s—like 1987’s Denchu Kozo no Boken (The Adventures of Electric Rod Boy), which centers on a boy with a large electricity pylon protruding from his back and features some of Tsukamoto’s soon-to-be trademark stylings. Heck, maybe you’ll even be fortunate to find someone else’s lost relic lying around—an unlabeled video cassette containing within it a reel of wobbly, almost irreparably worn tape primed to spark an obsession.