One of the greatest tragedies in anime history is the untimely death of director Satoshi Kon. In his relatively short career, spanning just four feature films and one TV series, Kon produced a remarkable body of work, showcasing an intelligence and consistency of vision that has yet to be surpassed by any other anime director.

Birth of a Genius

Like most visionary anime directors, Kon arrived at his unique style through a merging of East and West. A childhood filled with sci-fi anime for boys (Space Battleship Yamato and Gundam) soon gave way to the introspection and impressionism of shojo manga. In college Kon latched onto live-action American and British films, especially Terry Gilliam movies (Brazil, Time Bandits) and George Roy Hill’s adaptation of Slaughterhouse Five, about a  man who has become “unstuck in time.”

man who has become “unstuck in time.”

Kon started his career as a manga artist, and an acclaimed debut story launched him into an assistantship with legendary manga artist Katsuhiro Otomo. Under Otomo’s tutelage, Kon worked on manga titles like Akira and eventually published some of his own.

This collaboration with Otomo also led him into the anime industry. He drew backgrounds and animation for Otomo’s Roujin Z and later directed Episode 5 of the JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure OVA.

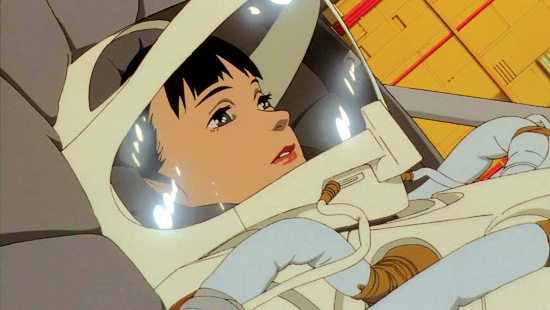

But Kon’s anime oeuvre really begins with “Magnetic Rose,” part of Otomo’s short film compilation Memories (1996). Directed by Koji Morimoto and featuring a script adapted by Kon from an Otomo manga, it’s a surreal sci-fi parable about astronauts who enter a decrepit ship, only to be ensnared by the holographic ghost of an opera singer. Illusions conjured from the astronauts’ memories and deliberately paralleled with the theatrical setting foreshadow much of Kon’s later work, though the directing isn’t as mischievous.

Kon the Director

Soon Madhouse producer Masao Maruyama contacted Kon, on Otomo’s recommendation, for an adaptation of the novel Perfect Blue. Originally slated as a live-action film, the new anime version required someone who could make “an animated film in a live-action genre,” according to Maruyama. Kon was a perfect fit.

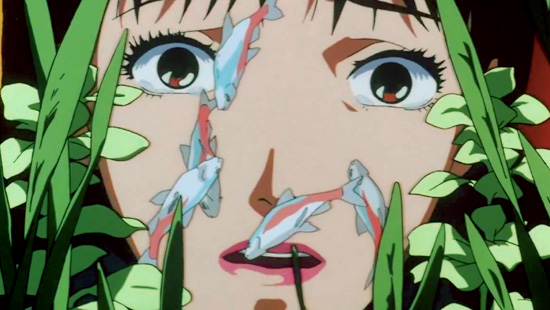

In Perfect Blue (1997), pop singer Mima has just embarked on a new career as an actress, but as new gigs erode her “pure” image, she has an identity crisis, believing she may be responsible for a string of murders. Perfect Blue has invited comparisons to Hitchcock, with its tight direction and highly uncomfortable portrait of a woman’s psychological breakdown.

Kon weaves a tricky narrative in which time is subjective and jumps

through time and space without warning. Perfect Blue solidified Kon’s relationship with studio Madhouse and producer Maruyama, both of whom would stick with him for the remainder of his career.

In Memories and Perfect Blue, Kon translated the disjointed temporality of Slaughterhouse Five into the realm of psychological horror, but for his next film he used these techniques for something far less sinister.

In Millennium Actress (2001), two documentarians interview an elderly actress and find themselves literally swept up in her story. Soon her real-life search for a teenage crush weaves its way into her film roles, blurring the line between fiction and reality. Kon’s love of match cuts (where the end of one shot matches the beginning of the next, like a car tire turning into the sun) is in full force, especially in its final scene, which splices the heroine’s life and films together in a stunning montage.

A few years after Millennium Actress Kon debuted Tokyo Godfathers (2003), about three homeless people who find a baby in the trash and seek to return her to her parents. Other than a single dream sequence, the story stays surprisingly grounded, but Tokyo Godfathers has a subtle undercurrent of magical coincidence, such that our heroes seem protected by a conspicuous, unexplained series of miracles.

This is no accident: Tokyo Godfathers takes place at Christmastime. The film also showcases Kon’s interest in outsiders and unusual subjects; few other directors would think to create an anime about Tokyo’s homeless or immigrant communities (which also feature prominently in Godfathers).

With the Tokyo Godfathers team finishing their contracts and Kon mulling over some “leftover” ideas from his trio of feature films, he came up with a way to keep everyone employed: Paranoia Agent (2004). The 13-episode TV series takes the ensemble cast of Tokyo Godfathers to its logical extreme, with a “relay race” of protagonists passing the narrative baton from episode to episode.

Each intersects with Shonen Bat (Lil’ Slugger in the dub), a middle schooler on roller blades who attacks with a golden bat. With stinging social commentary and a sober message about urban legends, Paranoia Agent is actually far more cohesive than its disconnected narrative would imply. The story was only initially planned up to Episode 7, but it’s a credit to Kon’s strong direction that the beautiful mess of a climax coalesces into a solid ending.

In more ways than one, Paprika (2006), Kon’s final film, was a “dream project”: it brought together his favorite novel (Yasutaka Tsutsui’s Paprika) and his favorite musician (Susumu Hirasawa, who provided soundtracks for Millennium Actress and Paranoia Agent). Out of this collaboration came a spectacular, if a bit uneven, film, in which doctors scramble to stop a “psychoterrorist” who has stolen their prototype dream-manipulation machine.

Backed by Hirasawa’s magnificent electronic score and featuring a literal parade of bizarre dream imagery, the movie still makes time for sly commentary on fantasy’s ability to both empower and entrap us. Paprika also gave us a line that sums up Kon’s depiction of reality through the lens of fantasy: “It’s truth that came from fiction.”

Unfortunately, Kon’s career came to a crashing halt in May 2010 when, at age 46, he was diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer. At the time he was hard at work on The Dreaming Machine, which he described as “a road movie for robots.” After cancer took his life in August 2010, the film remained unfinished, though Masao Maruyama, producer of Kon’s films and a close friend of the director, has said repeatedly that he wants to complete it, “no matter how many years it may take.”

The only other post-Paprika work Kon left us was a 2007 short called “Good Morning,” part of a series on the NHK. It wordlessly depicts a young woman waking up as ghosted-out versions of her groggily wander her apartment, replicating the disorientation of waking up. Her apartment resembles Mima’s in Perfect Blue, making “Good Morning” an inadvertently appropriate bookend to Kon’s career.

Being Mean in Order to Be Kind

Kon’s work features a number of recurring themes and motifs, including the obvious one: a blurring of fantasy and reality. He tackled real issues—the exploitation of women in idol culture, youth violence, Tokyo’s homeless population—with the understanding that our lives, no matter how bleak, are always tinged with hints of fantasy.

He preferred female protagonists, but also often showed male “fanboy” characters, whether as sinister stalkers (Perfect Blue) or benign protectors (Millennium Actress). These characters were always realistic, both in design and demeanor. Kon delighted in playing visual tricks using reflections and match cuts, and often talked of deliberately misleading viewers to achieve a desired effect (something he called “being mean in order to be kind”).

He also liked to repeat similar images and sounds within his works to create a sense of cohesiveness. Kon was always critical of anime, with its seductive wish fulfillment and overwhelming sameness, which drove him to transcend the “robots and cute girls” that his contemporaries were creating.

Andrew Osmond’s (excellent) book on Kon calls him an “illusionist,” but the sleight-of-hand is only part of the story. Satoshi Kon was a brilliant, restless artist who believed in the dignity of human beings and the important role of fiction in shaping our lives. Throughout his career, he performed the rare feat of capturing the human experience through the expressive power of the fantastic.

Nevertheless, in a tragic letter from his deathbed, Kon remained humble until the end. “With my heart full of gratitude for everything good in the world, I’ll put down my pen,” he wrote. “Now excuse me, I have to go.”