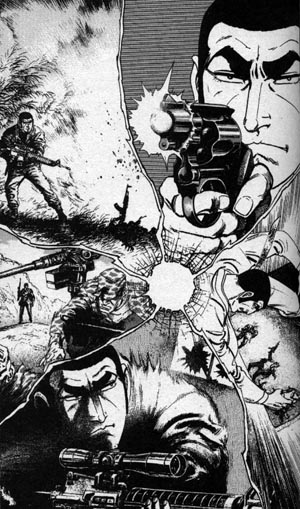

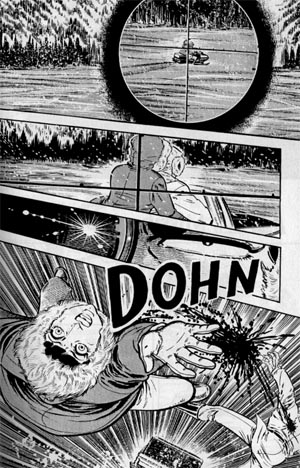

Originally created by Takao Saito, the world of Golgo 13 is a harsh one grounded in the very real arenas of government politics, brutal crime, sex and intrigue. Despite many helpings of action, most of the stories focus on people who may fear G13’s existence or presence in town. Known to the outside world as Duke Togo, he is the ultimate freelance hitman, used by various agencies, governments or individuals who have their own need for his services. His sniping skill is unparalleled, as he often uses a modified M-16 for various jobs, though he will call upon trusted gunsmiths for other kinds of weapons.

Originally created by Takao Saito, the world of Golgo 13 is a harsh one grounded in the very real arenas of government politics, brutal crime, sex and intrigue. Despite many helpings of action, most of the stories focus on people who may fear G13’s existence or presence in town. Known to the outside world as Duke Togo, he is the ultimate freelance hitman, used by various agencies, governments or individuals who have their own need for his services. His sniping skill is unparalleled, as he often uses a modified M-16 for various jobs, though he will call upon trusted gunsmiths for other kinds of weapons.

As one of the longest running gekiga (or “dramatic pictures”) manga produced in Japan, Golgo 13 has become ingrained in Japanese pop culture, sometimes lampooned in other anime and manga. In the U.S. however, the series has enjoyed only moderate popularity, mostly due to the 1988 Nintendo Entertainment System game, Top Secret Episode: Golgo 13, and Streamline Pictures’ dubbing and release of the animated film in the mid ’90s.

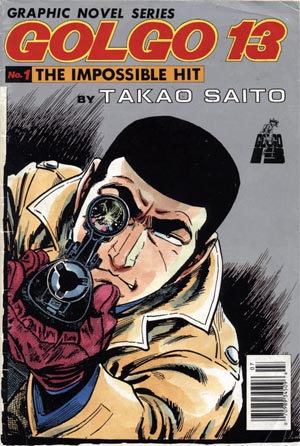

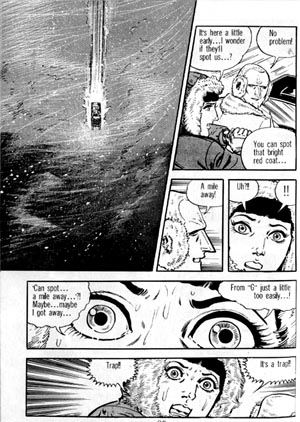

The manga has been published here in four different formats by various publishers. The first was done in 1986 by LEED Publishing Company, who released four graphic novels containing two stories each, translated by Patrick Connolly. The first one, “Into The Wolves’ Lair: The Fall of the Fourth Reich,” saw Togo take on a group of Nazis in Buenos Aires who were connected to John Hinckley Jr., the attempted assassin of President Reagan. Strangely, in this book the assassination attempt is slightly blacked out in a few panels, but Togo’s appetite for action is rather prevalent in this segment. The second book, “Galinpero,” is apparently a favorite story of Saito’s publishing group since it was animated as the 21st episode of the recent TV series. The third and fourth books were entitled “Ice Lake Hit” and “The Ivory Connection,” respectively.

The second release was also done by LEED Publishing but as a pair of single-issue comics, each in conjunction with the two NES games. The first one was known as “The Impossible Hit,” (which was also animated for the recent TV series as its second episode). This was translated to help promote the Top Secret Episode game. The other comic was also a single, but colorized and entitled “The Border Hopper,” meant to help promote the second NES game, The Mafat Conspiracy.

For the third release, LEED Publishing teamed with Viz Comics to release a miniseries entitled “The Professional: Golgo 13.” This was a translated and colorized version of “The Argentine Tiger” in which Togo is sent by the British government and given sickness pills to help him infiltrate a government hospital and assassinate Argentina’s former president.

For the third release, LEED Publishing teamed with Viz Comics to release a miniseries entitled “The Professional: Golgo 13.” This was a translated and colorized version of “The Argentine Tiger” in which Togo is sent by the British government and given sickness pills to help him infiltrate a government hospital and assassinate Argentina’s former president.

The most recent format came from Viz Media under their Viz Signature line. For this release, 26 stories were selected as the best out of hundreds and translated for the American market under the careful eye of editor Carl Gustav Horn. These were done closer to Japanese manga style than the previous formats in that the Viz Signature lines were not “flipped” to read from left to right. These last sets were done to celebrate the best of Golgo 13 and contained a lot of unusual bits of information about the character.

Golgo 13’s indispensability as an invisible force, or boogeyman-for-hire so to speak, is part of his lasting appeal to many readers. He’s brought into many real life situations that Saito Pro can take advantage of and create new challenges for Golgo 13. We asked former G13 editor Horn about these elements of conflict and several others that contribute to the series’ considerable following.

Golgo 13 has been produced for over 40 years now. What do you think is the secret of his longevity?

I think it’s because it offers its Japanese readers a special sense of perspective on the world’s issues and conflicts, a fictional viewpoint that is intriguing for them. Tomo Machiyama once said that part of the popularity of Gundam is that it enables Japanese people to enjoy a war story that’s free of the politics of their own past. Past conflicts are problem enough; current ones are unimaginable for Japan, even in fiction. Say you’re writing an American comics story, and you want to put in a scene with a U.S. Special Forces unit somewhere in the world. No one will say that’s unrealistic; we’d take an idea like that for granted. For Japanese people, giant robots are more believable than the idea Japan could or would send a bunch of black-ops types to some other country, let alone aircraft carriers and bombers. Even when Japan sent a battalion of soldiers to Iraq, it was purely to do reconstruction work and not combat; the Japanese soldiers were themselves guarded by Australian troops. Japan has had plenty of militarism in its past, but in the immortal words of Col. Trautman, “It’s OVER, Johnny!”

But of course, if you can’t write manga about a Japanese guy getting involved in conflicts around the world, that rules out a whole genre of action stories—again, the kind of stories an American reader would accept without a second thought. So what do you do if you’re a manga artist? You come up with a character like Golgo 13. Readers wouldn’t believe it if he literally were a Japanese James Bond—that is, if he were a secret agent working for the Japanese government. But they can buy the idea of a Japanese guy willing to go anywhere in the world for the sake of private business—after all, that’s how Japan built its export-driven postwar economy. He’s even got plausible deniability when it comes to being Japanese—the series has always suggested he’s at least part Japanese, but has refused to confirm his real name or ancestry.

The G13 character has been compared to the likes of James Bond, but you compared him to a different character altogether. Please elaborate.

The G13 character has been compared to the likes of James Bond, but you compared him to a different character altogether. Please elaborate.

The biggest difference between Bond and Golgo isn’t that Golgo is an assassin—after all, Bond has that license to kill—it’s that Golgo is not a government agent and has no boss and no allegiances. He may do a job for this country or that country, but it’s strictly on an independent basis. So I thought the better comparison was to “The Jackal,” the protagonist of Frederick Forsyth’s 1971 novel The Day of the Jackal, and the 1973 movie of the same name. Like Golgo, The Jackal is a freelance assassin whose real name is unknown, who uses false identities and disguises, demands big fees for a job, and uses a customized sniper rifle. Forsyth’s novels (at least the early ones) also resemble Golgo 13 more than James Bond, in that the antagonists aren’t super villains, but businessmen, politicians, and intelligence agents with real-world agendas.

How did you get the information to do the write-ups in the back, such as G13’s sniping style and an accounting of all the money he’s made? Were the original creators and co. helpful for this?

The reason I wanted to have “File 13,” the liner notes section, was to give English-language readers a sense of the breadth and history of the series. After all, the Viz series could only feature 24 of those 500+ stories (less than 5%!). Whereas usually, when I work on liner notes, they refer to what’s happening in the volume itself, “File 13” generally referred to things that happened [in] other volumes of Golgo 13—ones that may never be translated or published in English. “File 13” is meant to give you a sense of that other 95%.

The basis of the “File 13” liner notes were translations of various articles from the Japanese book “Encyclopedia of Golgo 13“—but this was a book meant for Japanese fans who could be expected to have most or all of the entire series to consult. Since that probably wasn’t the case for the average reader of the English version, I would take the “Encyclopedia” entries as a starting point, and expand on them. For example, if it made reference to, say, Golgo 13 story #134, I would break story #134 out of the library and see what exactly they were talking about, and then incorporate a description into the article. More than cross-references to other Golgo stories, the “Encyclopedia” also assumes its Japanese readers will know about things like the history of Manchukuo, or who people like Gensui Togo or Kunio Suzuki are. In order for such references to be useful to the English reader, I had to explain them further. And some elements in “File 13” were entirely original, such as the observation on Will Eisner’s M16 comic book, or the discrepancies in Golgo 13’s income, or of course, the afterwords.

What made you choose the stories you translated out of the hundreds that were available?

What made you choose the stories you translated out of the hundreds that were available?

Golgo 13 was originally planned back in 2001, when it was still the practice to release manga not straight to graphic novel, but first one chapter at a time as monthly comic books, and in fact, that was going to be its original format, with covers by Tim Bradstreet, who at the time was doing The Punisher. The particular 26 stories were chosen for various reasons; one was to show a mix of eras, and so the stories range from 1972’s “Misfire” to 2001’s “Flagburner.” Another goal was to pick stories that featured personalities that would be known to North American readers, such as Bill Clinton, Nelson Mandela, and Pope John Paul II, and also well-known events (Why were there no WMDs found in Iraq? Golgo. Who fixed the 2000 U.S. Presidential election? Golgo…).

Conversely, some stories were picked for the opposite reason, centering around European or Asian issues (like “Germany Is One,” or “A Fierce Southern Current”) to give a sense of the series’ topical range. Some were picked in part to show off a technical aspect of Golgo’s sniping (although the idea he always makes some bizarre shot is one of the myths of the series, together with the claim he never smiles). I wanted to also include one of Duke Togo’s possible origin stories (the series had several, deliberately contradictory theories about where he came from), and so included “The Serizawa Family Murders.” I picked some of the stories that inspired the 1983 Golgo 13 anime film like “Hydra,” and “Far From An Era,” since potential readers might have seen the movie. And finally, I chose one of the rare humorous Golgo 13 stories, “The Wrong Man,” both to show that the series isn’t always serious, and that it’s willing to make fun of the myth of Duke Togo.

There were also personal feelings; one Golgo 13 story I felt strongly about was “The Deaths of June 3rd,” which concerns the events leading up to the Tienanmen Square massacre of 1989. When I was eighteen, my cultural heroes were Japanese, but my political heroes were Chinese—during the spring of 1989, the entire world looked towards Beijing with admiration, as a symbol of courage and ideals—something that, sadly, seems very hard to believe today. Considering the tragedy, “The Deaths of June 3rd” is a surprisingly nuanced look at the issues, including the complex historical relationship of Tibet to China, and the moral question of Buddhist non-violence in a world of tank columns, and, of course, of assassins.

Another of my goals in picking the stories was to give a sense of the morality and meaning of assassination as it happens in the real world. Golgo’s been around since the sixties, which makes him one of the closest things manga has to ageless, American-style superheroes who last for decades, and get written and drawn by different people over the years. The classic idea of American superheroes is that they have a code against killing; nevertheless, stories debate the morality of their vigilante justice. But killing is all Golgo does. What is his morality as manga’s longest-running “hero”?

If you think about it, Superman and Batman are in the odd position of claiming a higher moral ground than the forces of law and order they serve. That is, they may have a code against killing, but the government doesn’t, whether it comes to the death penalty, war, or assassinations. Golgo 13 began in 1968, seven years before President Ford, in the wake of the Church Committee (and both Ford and the Church Committee appear in the Viz stories, again not by accident), signed an executive order forbidding the U.S. government to use assassination as a policy.

If you think about it, Superman and Batman are in the odd position of claiming a higher moral ground than the forces of law and order they serve. That is, they may have a code against killing, but the government doesn’t, whether it comes to the death penalty, war, or assassinations. Golgo 13 began in 1968, seven years before President Ford, in the wake of the Church Committee (and both Ford and the Church Committee appear in the Viz stories, again not by accident), signed an executive order forbidding the U.S. government to use assassination as a policy.

Today, we again take such “targeted killings” for granted as part of the war on terror. But when Golgo targets someone, it’s that person only, whereas when a Predator drone launches a Hellfire missile, it’s going to take out the actual target, as well as anyone else who happens to be around. It was reported that in 2009 the CIA suspended an alternate assassination program that actually used agents on the ground instead, so as to reduce collateral damage–but ironically, using such “hit men” is more controversial than remote-control drone missions; perhaps because a Predator, with its high-tech hardware, seems like a military attack instead of an assassination. One of the Golgo 13 stories I chose, “A Fierce Southern Current,” goes cynically beyond even the moral issue of assassination to ask whether, in the real world, governments really want to use the most efficient way to kill their enemies. An arms broker points out to Duke that there are a lot of politicians and generals who’d rather spend twenty billion dollars on a weapons system that might or might not work—because it means twenty billion worth of domestic jobs, prerogatives, and prestige—than one million on Golgo 13, when he’s guaranteed to work.

Recently the first box set of the Golgo 13 TV series was released by Sentai Filmworks. Check out our review in the latest issues of Otaku USA and see if you can pick up previous animated films—The Professional: Golgo 13 and Golgo 13: Queen Bee—for some good crime noir anime.

![[Review] Ghost in the Shell Deluxe Edition Manga [Review] Ghost in the Shell Deluxe Edition Manga](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/gitsdeluxeheader-480x360.jpg)