Rewatching Ghibli’s Porco Rosso the other day, I was reminded that, before live-

action films starting relying increasingly on computer effects (what percentage of,

say, Gravity is actually filmed footage?), animation used to be the exclusive home of

a kind of breathtaking movement impossible in live action. The twists, turns and rolls

of the airplanes in that film are simply magical, especially when you really step back

and remember all that sense of movement comes simply from (very talented) men and

women making drawings on paper.

Patema Inverted is no Ghibli masterpiece, but at its best moments, it’s a reminder of

that same power of animation.

Patema is the second full-length film from writer/director Yasuhiro Yoshiura, the creator

of Time of Eve. Like Time of Eve, Patema started as a original net animation before

being made into a full-length film.

The film begins with archival footage of a scientific experiment gone awry. Scientists

attempting to create anti-gravity technology instead reverse the gravity of the entire

planet, sending entire buildings flying (or falling, technically) into the atmosphere.

Cut to many years later, when two distinct civilizations have emerged – those whose

bodies maintain their original gravity (that is, they can stand firmly on the ground), and

“Inverts,” those who have been flipped. They live underground in a complex maze of

tunnels that would appear upside-down to those on the surface.

The two civilizations avoid contact, thinking the worst about each other, but each

side also has its few dreamers who wonder what life is like on the other side. For the

Inverts, this is Patema, a young girl who, against the orders of the elders, explores the

underground caves farther every day until she “falls” through a passage and into the

world above ground. She’s saved from falling endlessly into space by a young above-

worlder named Age.

This is where the real power of the film lies. To Age, Patema appears upside-down, her

legs firmly planted on the ceiling. But for Patema, of course, the reverse is true, and the

camera continually switches perspectives, showing us what things look like from both

points of view. The first time it happens, it’s the kind of “wow” moment that reminds you

of the power of animation.

And these wow moments continue whenever the film springs into action. An early scene

involves Patema and Age running from the film’s villains. By taking Patema’s hands

in his, Age is able to use her reverse gravity to jump great distances, as if he were on

the moon. The feeling of flight is exhilaratingly animated, giving the viewer butterflies

as they imagine themselves hurtling through the air. Scenes later in the film introduce

more Inverts interacting with the world above ground, and its thanks to the skillful hand

of director Yoshiura that we’re constantly wowed but rarely overwhelmed or confused

whenever he flips the camera.

Patema is more of a mixed bag when the emphasis is on story, though.

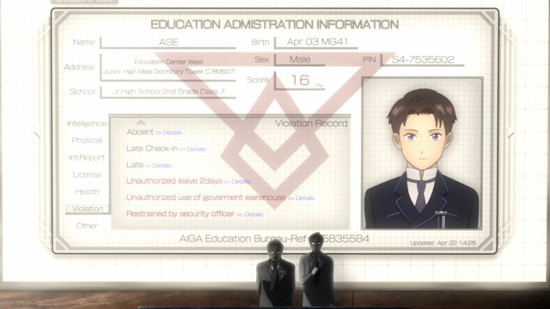

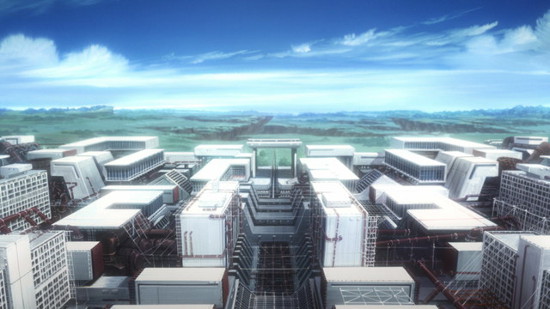

Age’s home, the above ground world of “regular” gravity, is a kind of Orwellian society,

where Inverts are demonized, individuality is repressed, and dreamers are dealt

extreme punishment. It makes sense in the context of the film, but there’s little to

distinguish it from the standard evil, totalitarian society we’ve seen in dozens of other

films. The leader is especially one-dimensional, cackling evilly while holding his hands

over his mouth.

Patema’s society is equally cliched, with wizened old elders spouting wisdom and

keeping dangerous secrets to themselves. The relationship between Patema and Age is

a bright spot, though – they seem genuinely linked by a common philosophy, not simply

sticking together for the sake of the plot.

Patema is full of twists and turns (appropriate, considering the gravity premise), but

things don’t always quite click, plot-wise. But the joy of the film definitely comes from

those moments where the audience is invited to invert their minds and see things from

a new perspective. Its action sequences are a great reminder of the still-potent power of

animation.