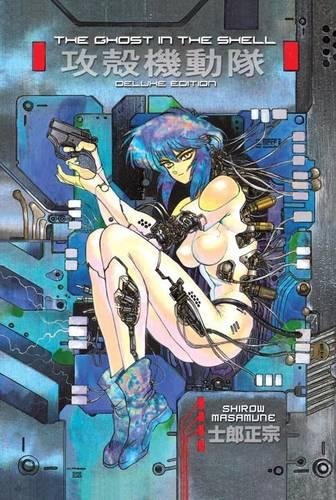

Kodansha’s deluxe reissue of Masamune Shirow’s seminal Ghost in the Shell (scheduled, no doubt, to capitalize on the live-action film’s release) fixes many of the concerns fans had with earlier editions. No longer is it flopped, nor have the original sound effects—their presence an essential part of Shirow’s painstakingly rendered and gorgeous environments—been replaced with clumsy English approximations. If the hardcover binding feels cheap, more like a chipboard box than a lavish coffee table book, it is a vast improvement over the earlier paperback’s flimsy binding. The infamous sex scene censored from Kodansha’s earlier release is still missing for reasons impossible to explain and the paper still feels too pulpy to earn the designation “deluxe,” but no other edition has so well presented Shirow’s gorgeous artwork.

Kodansha’s deluxe reissue of Masamune Shirow’s seminal Ghost in the Shell (scheduled, no doubt, to capitalize on the live-action film’s release) fixes many of the concerns fans had with earlier editions. No longer is it flopped, nor have the original sound effects—their presence an essential part of Shirow’s painstakingly rendered and gorgeous environments—been replaced with clumsy English approximations. If the hardcover binding feels cheap, more like a chipboard box than a lavish coffee table book, it is a vast improvement over the earlier paperback’s flimsy binding. The infamous sex scene censored from Kodansha’s earlier release is still missing for reasons impossible to explain and the paper still feels too pulpy to earn the designation “deluxe,” but no other edition has so well presented Shirow’s gorgeous artwork.

Nor are the changes purely cosmetic: the footnotes Shirow peppered early releases with have been expanded ten-fold in an effort to flesh out the universe and explain many of the vaguer aspects of the story and the author’s abstruse philosophy. And it is necessary. Shirow is an ambitious world-builder curious to explore how the body and identity intertwine and how political structures influence our perception of both, but his vision uniformly exceeds his abilities in almost every field. He seems incapable of settling on the voice of his characters; the only one who has a defined personality is Motoko, and in all instances she comes across as a mouthpiece meant to express Shirow’s own views. A group of protestors who find Japan’s interference in Middle-Eastern politics despicable earn only a contemptuous snub from Kusanagi; “they’re so hypocritical,” she grouses,” emphasizing a lifestyle based on consumption is the ultimate violence against poor countries,” and behind her you can hear Shirow himself scoffing at the perceived stupidity of his political opponents.

Not that his vision of this world’s geopolitics is coherent enough to add up to a political philosophy he might defend; in one footnote he even mentions that “(he’s) not sure what (one character) means about (another character) sending aid. It’s a mystery.” Never mind that the situation he’s talking about concerns the deposed leader of a country whose presence in Japan has massive repercussions for Japan’s international standing and for our characters. Meanwhile, his grasp of more traditional philosophy is sophomoric, his command of philosophical language tortured. It takes the better part of 20 pages for Shirow to explain that offspring tend to diversify to avoid extinction and this only after wasting precious time trying to force a metaphysical explanation about the nature of the universe out of a fact so commonly acknowledged that even mentioning it seems trite.

It often seems like the only thing Shirow cares enough to explain carefully are details about the technological minutiae of this cyberpunk future, with his true concern less how these advancements might alter identity and more with lengthy diatribes that read like Shirow’s own rejected theses for how one might implement these technologies. Most often they take the form of footnotes squeezed into the margins to explain away things like the catch of a gun, or the purpose of wire cutters on a helicopter. In other parts they are so shoddily inserted into the narrative—often times interrupting a case just so one character can meditate on how plastics are used to emulate sensations of pressure instead of talking about their own feelings on a case—and so fragmented in their purpose that they do not clarify the world. They muddy it.

The result is a story that reads as far more complex than it actually is. Though he is often compared favorably with cyberpunk luminaries such as William Gibson and Katsuhiro Otomo, the truth is that in his fetishistic obsession with technological minutiae and his fascination with state violence that often skews towards worship Shirow has much more in common with the likes of pulp hacks like Michael Crichton and Tom Clancy. The interconnected stories that comprise Ghost in the Shell are not much more complicated than your typical police procedural. Criminals with international origins and/or intentions make a play in Japan, Motoko Kusanagi and the rest of Public Security Section 9 are brought in to deal with the situation lest it spill-over into a global fracas, and after much gunfire and loving looks at meticulously designed military hardware the case is wrapped. An effort is made at the last minute to tie in earlier mentions of the hacker known as the “puppeteer” to a larger conspiracy and the conclusion of Motoko’s own character arc, but Shirow is such a daft storyteller that it fails to tie together earlier thematic concerns as he might have wished. This is a messy, uncertain work that possesses neither the melancholy beauty that made Oshii’s film such a critical darling nor the political insight and philosophical inquisitiveness that elevated Kamiyama’s similarly structured Stand Alone Complex. Interesting and essential as a piece of art history, yes, but mostly dismissible as a piece of art.

Publisher: Kodansha