My collection is too massive. It’s a monster, a monster that feeds on disposable income, time, and space. Yesterday I bought a sixth bookshelf in a feeble attempt to contain the onslaught of movies, manga, and roleplaying books threatening to burst out of my bedroom and overrun the house. I spent the entire day building, arranging, organizing, reorganizing, tinkering, tweaking, and schlepping huge stacks of material from shelf to shelf. There’s a silver lining amidst all of this effort, though, because sometimes I discover a gem in my collection that I completely neglected to watch.

That gem is Orochi the Eight-Headed Dragon, originally entitled Yamato Takeru. Orochi is a live-action tokusatsu film released in 1994 and produced by Toho Studios. It’s a fanciful retelling of the life of Yamato Takeru, one of Japan’s most famous mythological heroes. It’s also completely bonkers.

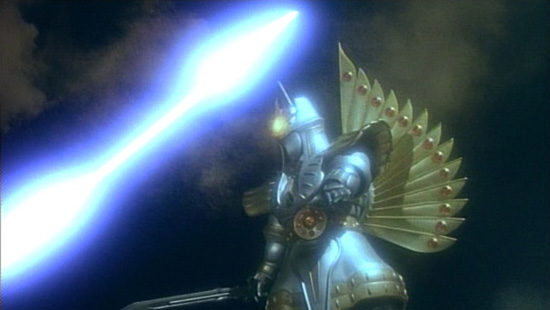

After a brief invocation involving a double-decker UFO, the movie opens with a sinister minister tossing a baby off of a cliff. Born under inauspicious circumstances, Prince Ousu, the youngest brother among a set of twins born to the Emperor of Yamato, has been sentenced to execution. Luckily for young Prince Ousu, Amaterasu Omikami, the goddess of the sun, intervenes to save his life. Saving plummeting babies in this case requires the deployment of a robot phoenix. Prince Ousu is raised by his aunt, a priestess of Amaterasu. He grows to manhood and discovers his heroic destiny, which allows him to shoot green lasers from his eyes. Prince Ousu takes the name of Yamato Takeru and performs great deeds such as thwarting the evil plans of Tsukiyomi, the god of the moon, and slaying the titular eight-headed dragon.

I haven’t even mentioned the giant robot yet.

This film is wonderful. It’s everything I want a modern take on mythic storytelling to be: bold, broad, and unashamedly goofy. Masahiro Takashima (Gunhed, Godzilla vs Mechagodzilla II) is frightfully earnest in the lead role of Yamato Takeru, whereas Hiroshi Abe (Thermae Romae, Chocolate) chews the scenery as the villainous Tsukiyomi. Director Takao Okawara, a veteran of five Godzilla films, wields his considerable expertise to create a world where evil wizards sling curses and human heroes go toe-to-toe with dastardly deities.

Of course the real stars of any tokusatsu film are the special effects. Orochi uses nearly every trick in the visual effects handbook: puppetry, suitmation, green screen, forced perspectives, matte paintings, post production optical effects, wirework, and even primitive CG for morphing and particle effects. The practical effects shine for the movie’s monsters. Orochi treats the audience to a wicked volcano god with molten magma pulsing beneath its cracked skin, a sea serpent with lashing tentacles and flexing frills, and an eight-headed dragon that shoots real flames from its many mouths. The film’s human-centric action scenes include flashing swords, smashing scenery, and a few surprisingly gruesome impalements. If there’s one noticeable weakness in Orochi’s production design, it’s that the locations look more like flat wooden sets than classical castles or ancient caves. But as a person who grew up on such sword-and-sorcery / sword-and-sandals fare as Red Sonja and Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, I’m willing to forgive.

There’s something psychologically refreshing about mythic storytelling, where the magic and mystery of the subject matter elide the typical concerns of film criticism. When dealing with a world of gods and monsters, the usual rules of storytelling don’t entirely apply. The characters don’t have to be three-dimensional or realistic, because verisimilitude isn’t the chief consideration. Antagonists can be as one-dimensional as the transparently evil soothsayer Tsukinowa or as bombastic as the moon-god Tsukiyomi, and it ultimately doesn’t matter because these characters aren’t supposed to have human motivations. Yamato Takeru doesn’t require a dramatic need, although the script attempts to give him one anyway. He conquers the bad guys because that’s what mythological heroes do. Likewise, the plot doesn’t have to remain logically consistent. The script can pull an improbable transformation out of nowhere and my suspension of disbelief is never threatened, because that’s just the sort of thing that happens in myths and legends.

I’ve owned Orochi the Eight Headed Dragon for the better part of a decade. For ten years, it has sat in my Vault, unloved and forgotten. Discovering it among my possessions was like the “call to adventure” in Joseph Campbell’s oft-quoted Journey of the Hero mono-myth. It was the unexpected quirk of fate that sets a tale in motion. Thanks to Orochi the Eight Headed Dragon, the mundane task of putting my living space in order culminated in a mystical journey, and for that I am as grateful as I can be until the next discovery, the next great cinematic journey, comes along.

Distributor: ADV Films

Originally released: 1994

Running Time: 105 minutes