Hironobu Sakaguchi’s announced return to RPG creation via the newly formed Mistwalker Studio in 2004 was much rejoiced by those who believed at the time that Square Enix was a sinking ship, and sought the father of Final Fantasy’s new company to bring back something of a renaissance. What they got instead would ultimately fail to meet those expectations. 2005’s Blue Dragon was to harken back to the days of the legendary dream team that birthed Chrono Trigger solely by virtue of being a collaboration between Mistwalker and Akira Toriyama’s Bird Studio. The result was a game that had solid mechanics (assuming you liked Final Fantasy V) and a good bit of visual charm, but was ultimately polarizing due to its Saturday morning cartoon-level plot and boring characters. 2007’s Lost Odyssey was poised to be the game we’d been waiting for Sakaguchi to make since his departure, and unlike Blue Dragon, had solid characters and excellent writing thanks to novelist Kiyoshi Shigematsu. However, it was plagued by long load times and some intensely frustrating boss battles that hindered the pacing of its narrative.

Fast forward to 2011: in an era where open-endedness and player “freedom”—two things Japanese RPG developers have seldom been known for—are emphasized in modern role playing games, the relevance of the Japanese RPG itself is becoming more questionable. Many scoffed at Nintendo of America’s apparent disinterest in bringing both Xenoblade and The Last Story stateside; a common argument for the latter’s release is that being able to stamp a gold “From the creator of Final Fantasy!” sticker on the front of the box alone should be enough to warrant an international release. But this is no longer the era of the Japanese Role Playing Game boom, and the sad truth is that this may not be the case.

Which is a shame, because The Last Story is one of the best role playing games to come from Japan in ages, and easily the best thing Mistwalker have done to date. Simply by returning to the drawing board for how Japanese role-playing games became what they are in the first place—amalgams of western aesthetics and design with Japanese know-how and sensibility—it reminds us what’s good about the Japanese approach to begin with.

The Last Story, on the surface, isn’t too different from your average RPG. The player’s plucky main character du jour is Elza, an orphan with a hazy past who joins a ragtag band of mercenaries aiming to become respectable knights. Hardly unfamiliar territory. But what matters in a JRPG is not actually the story itself, but the way it unfolds—and perhaps, even more importantly, the sense that things are progressing. To hone that end, The Last Story goes back to the very source of the genre in the first place: western games. Some may tend to balk at the Japanese industry’s current bend to looking westward for inspiration, but in reality Japanese games have always taken what works in Western games, trimmed the fat, and streamlined the overall experience with a Japanese style and sensibility. If that seems far fetched, let us not forget that Dragon Quest, for example—long since considered the progenitor of the role playing game as the Japanese know it—would not exist without Ultima. In this same fashion, The Last Story owes more to, say, Gears of War or Fable than any game to have come from the land of the rising sun that precedes it, including anything that Sakaguchi himself has had a hand in.

Despite its namesake, The Last Story is actually a game about progression, one that harnesses the thrill that comes from continually evolving and moving forward in a world built against the player. Rather than being a matter of your stats outclassing that of your enemies, combat in The Last Story is seamless and involves using a careful grasp of the situation as well as player finesse to break through enemy defense. In the same way that many console mainstay JRPGS have done of late, gone are random menus and battle commands—close-range combat is fully automatic, with active player roles consisting of guarding/dodging, giving commands to other characters, and using limit-break style abilities as necessary.

But the key to victory in The Last Story lies not in cycling through commands or increasing your characters’ numbers, but learning what each type of enemy is capable of, and how to control your party accordingly, as well as when to deliberately draw enemy attention to Elza. By unleashing Elza’s “Power from the Unknown Country,” you’ll be able to draw the attacks of all enemies solely to Elza. This is absolutely crucial—certain enemies can only be damaged by magic or elemental attacks, and if your magic users are getting pelted, you have no chance of victory. In other times, certain enemies may be impervious to all attacks but can be defeated by beating all other enemies first, leaving you to draw their attention while your other party members do the dirty work. Assuming you survive, of course. And this whole time, you’ll also be reviving downed allies and protecting yourself, as well.

But the key to victory in The Last Story lies not in cycling through commands or increasing your characters’ numbers, but learning what each type of enemy is capable of, and how to control your party accordingly, as well as when to deliberately draw enemy attention to Elza. By unleashing Elza’s “Power from the Unknown Country,” you’ll be able to draw the attacks of all enemies solely to Elza. This is absolutely crucial—certain enemies can only be damaged by magic or elemental attacks, and if your magic users are getting pelted, you have no chance of victory. In other times, certain enemies may be impervious to all attacks but can be defeated by beating all other enemies first, leaving you to draw their attention while your other party members do the dirty work. Assuming you survive, of course. And this whole time, you’ll also be reviving downed allies and protecting yourself, as well.

The typical game flow is as such: the game puts you through a series of events, with the opportunity to break for exploration or side-quests on your own time. When you’re ready to head out, you’ll talk to the appropriate character to move to your target “zone.” There’s no explorable world map in The Last Story, and most zones cannot be returned to when you’re done with them. Once you’re in the zone, the goal is clear: move forward, defeating each arena filled with enemies that you come across, and move onward until you beat the boss at the end. Similar, once again, to Gears of War, your party members converse with you about each situation and move the action along as you make progress. Once you’ve encountered enemies, the camera will zoom out as your party members comment on the situation—you’ll have the opportunity to move the camera around and see exactly what you’ll be up against; the battle doesn’t start until you confirm it.

Weigh your opponents—if they haven’t noticed your presence yet, sneak around the arena and use your bowgun or have other members cast spells to get the jump on them. As a general rule of thumb, your priority is to get rid of archers and magic users first, and dispel any active enemy heal circles. In any case, make your moves accordingly, and dispatch the enemies as quickly as possible. Experience points are distributed at the end of each conflict, and leveling up in the game almost seems like a genre formality, because I never once had to go out of my way to do it. At the end of each area, you’ll fight a boss of sorts, which will usually require you to think carefully about what kind of techniques to use and when to draw enemies with Elza’s power. Defeating the boss typically triggers a cutscene after which you are taken back to explore the town or start the next event immediately if you want, but whatever you do, something is always happening, and the urgency to move forward to that next event, that next battle or scene, is always tangible.

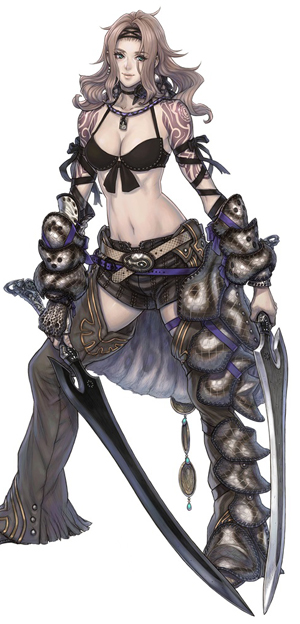

.jpg) The Last Story is not the first game to ape Gears of War in terms of progression, of course. But it works here as opposed to other games that tried this same formula (I’m looking at you, Final Fantasy XIII) because, rather than shoehorn Western genre tropes into an existing formula, The Last Story integrates the best parts of the genre from both sides of the world such that something new is created without anything essential being lost. Aside from streamlined combat and progression from event to event, there are several opportunities to branch out and explore the game’s lone—but stylish, labyrinthine, and European in design—town, resulting in plenty of opportunities for character interaction, side quests, and deliberate player choices involving the townspeople (including launching banana peels for hapless townspeople to slip on, if that’s your bag). Whatever you decide to do, heading out into town before taking on that next big event will lead to treasure hunting in back alleys, stopping fights, battles at the coliseum, taking on side quests and sub missions, as well as finding equipment and dyes to customize your characters. And in that regard, there is a lot you can do in The Last Story—all character equipment for both Elza and the non-playable characters actually shows up on the character in question. As if that wasn’t enough, by collecting “magic dyes” you can make and unlock colors which can be applied to each individual part of your character, and then on top of that there are effects you can add to the outfits, including—if you so wish—transparent clothes.

The Last Story is not the first game to ape Gears of War in terms of progression, of course. But it works here as opposed to other games that tried this same formula (I’m looking at you, Final Fantasy XIII) because, rather than shoehorn Western genre tropes into an existing formula, The Last Story integrates the best parts of the genre from both sides of the world such that something new is created without anything essential being lost. Aside from streamlined combat and progression from event to event, there are several opportunities to branch out and explore the game’s lone—but stylish, labyrinthine, and European in design—town, resulting in plenty of opportunities for character interaction, side quests, and deliberate player choices involving the townspeople (including launching banana peels for hapless townspeople to slip on, if that’s your bag). Whatever you decide to do, heading out into town before taking on that next big event will lead to treasure hunting in back alleys, stopping fights, battles at the coliseum, taking on side quests and sub missions, as well as finding equipment and dyes to customize your characters. And in that regard, there is a lot you can do in The Last Story—all character equipment for both Elza and the non-playable characters actually shows up on the character in question. As if that wasn’t enough, by collecting “magic dyes” you can make and unlock colors which can be applied to each individual part of your character, and then on top of that there are effects you can add to the outfits, including—if you so wish—transparent clothes.

These may seem like small details, but it’s the details that make a game come to life, and the result is the best of what both Western and Japanese RPGs do well. The story and battles give the player something to look forward to, are always challenging, and continuously give the player a sense of accomplishment through overcoming obstacles. Exploring the game’s vast and well designed town offers the chance to branch out and make choices; namely, opportunities to make the game your own. The Last Story walks a delicate line here, aiming to please parties of both styles of play and risking pleasing neither, but succeeds through flexibility—you are rarely forced to explore the town past the game’s expository stages, and there’s no real filler in between events unless you really look for it.

If there’s anything The Last Story doesn’t do well, unfortunately, it’s that when the burden of motivating the player through plot-progression must be carried by the characters, they can’t do it. Visually, the characters are well designed—and the ability to fully customize both clothes and colors for each character is a welcome addition—but personality-wise they fall into the age-old JRPG stereotype of giving each character a single, basic personality trope (the hyper-average main character, the waif-like princess, the stoic leader with a questionable past), and have them play it out ad-infinitum. When certain non-playable characters leave (read: die), it’s hard to care because it feels like so little time has been spent developing them that we barely even know who they are until after the fact.

But it’s the storyteller that matters in a Japanese RPG, not so much the story itself. Here Sakaguchi proves himself again in that regard, and the result is the game we’ve all been hoping he would make since 2004. By the time you read this, The Last Story may have already been slated for release in the United Kingdom, along with that other Wii RPG that you aren’t going to get, but anyone willing to go the other way and import the English version of the game will be glad they did. The Japanese role playing game may not mean as much globally as it did in the few years following the Western release of Final Fantasy VII, but if The Last Story is any indication, as long as people who truly understand the genre keep making games, they’ll be as relevant as they always were.

Publisher: Nintendo

Developer: Mistwalker

System: Nintendo Wii

Available: Now (Japan), 2012 (Europe)