Please don’t wake me

There’s no time of year I dread so much as late summer. Even now, almost a decade removed from the concept of summer vacations and the dread of school’s impending return, the wan lighting and redoubled, oppressive heatwaves that herald the last gasps of the season fill me with a sense of finality. As if something were dying. No matter how old I get I can’t shake that sense of an ending, can’t shake the ghost of a melancholy that always settled on me in the days leading up to the first day of classes as I faced the depressing reminder that those carefree days with friends were not as eternal as they seemed. That all things must end.

It’s unlikely that director Mamoru Oshii was attempting to capture this exact feeling with Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer. For one, the cultural context is vastly different: summer vacation for Japanese students is much shorter and comes not at the end of the school year but in the middle of it, after all. Any sense of transition attached isn’t half so melancholy. What’s more, Beautiful Dreamer is such an important hallmark in Oshii’s career and spends so much time interrogating his ever-present preoccupation with the razor-thin line between perception and reality—and how those systems that mediate our interactions with the world around us likewise mediate our apprehension of that reality—that it’s easy to get caught up talking about the historical importance and philosophical themes of the film.

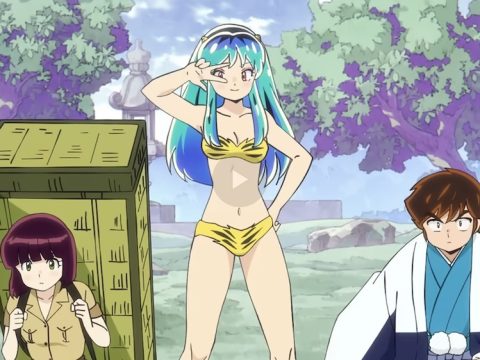

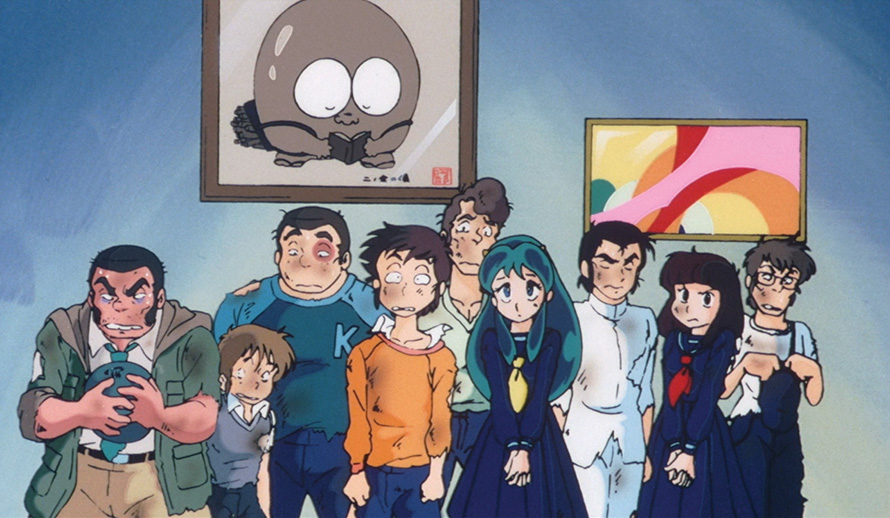

Less ambitious viewers might point to the movie’s similarities to Groundhog Day, but these similarities seem especially superficial when one realizes Beautiful Dreamer preceded Groundhog Day by almost a decade, or when one considers it derives its central conceit from the Japanese folktale of Urashima Taro. A more ambitious viewer could easily mount a convincing argument that Lum’s wish to spend all eternity with Ataru and their friends in an eternal summer is a sly bit of commentary on the formulaic nature of the entire Urusei Yatsura franchise from Oshii, or even Oshii’s own disillusionment after years spent working on the Urusei Yatsura television series. So much of Urusei Yatsura’s appeal—and indeed the appeal of other long-running sitcoms—lies in their accessibility from episode to episode, which in turn depends on rigid adherence to a familiar and comfortable status quo. These characters are already trapped in an endless loop of barely distinguishable days; creators and fans both have already seen to that.

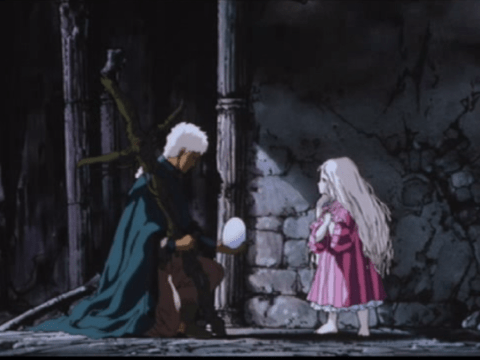

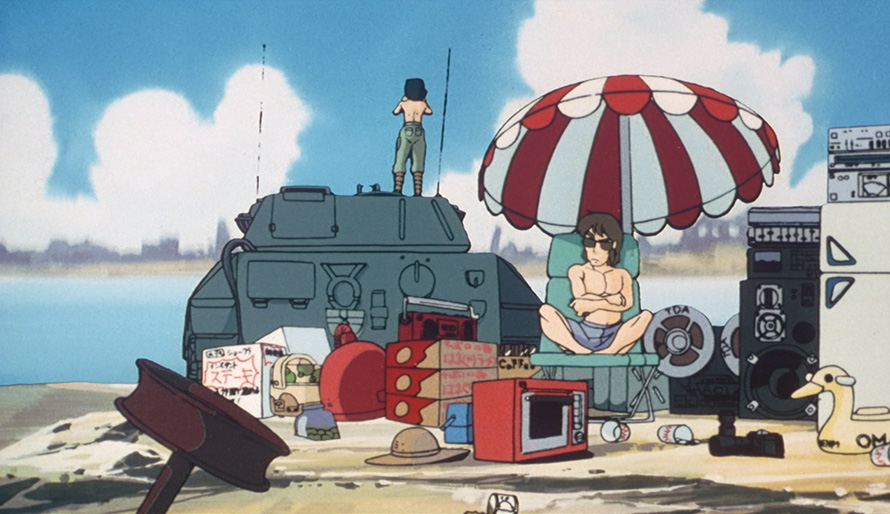

Yet even that reading fails to account for a melancholy yearning present here in every element, a resonant reminder that even these days, too, shall pass made all the more painful because it is delivered by a character who seems destined to a kind of comedic eternal recurrence. Lum and Ataru and their crew are drawn from a swath of broad and familiar character archetypes that became all the more familiar and so dull as a result of of their unchanging nature; they were intended only to serve as vehicles for comedy. There’s something deeply sad in realizing that even these unchanging types are subject to passing, a sadness made manifest most powerfully by a number of the directorial choices now easily recognizable as hallmarks of Oshii’s. The long, lingering views of urban dilapidation and empty cityscapes emphasized by a low-mixed score sounding as ominous as it does pained; the rolling waves of heat that the obsessive attention to details of military hardware and architecture that better serve to emphasize the extent and so the sense of decay and abandonment; a propensity for long tracking shots that bend and twist fluidly to lend space and time Escher-like dimensions: all of these elements together serve as almost palpable reminders that Lum’s fears of a changing world are all too relatable. Overlaid as they are with rolling waves of heat and a scorching sun they feel like those last sad days of summer made manifest.

It’s an ethos that seems outright hostile to Lum and Ataru’s carefree world, and yet it comes across with an earnesty that suggests Oshii’s intentions are not hostile but sympathetic. As if he, too, understands all too well the wretched sense of finality that accompanies the end of youth. In that light Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer is not so much an advisory fable about the necessity of maturing nor a caution about the dangers of nostalgia, whatever the central motif and reference to the Urashima Taro myth suggests. It feels instead like an elegy, notes written by a mourning composer looking back on lost halcyon days that conveys as much the joy of that lost era as it does the author’s present sorrow over losing them. Recommended.

It’s an ethos that seems outright hostile to Lum and Ataru’s carefree world, and yet it comes across with an earnesty that suggests Oshii’s intentions are not hostile but sympathetic. As if he, too, understands all too well the wretched sense of finality that accompanies the end of youth. In that light Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer is not so much an advisory fable about the necessity of maturing nor a caution about the dangers of nostalgia, whatever the central motif and reference to the Urashima Taro myth suggests. It feels instead like an elegy, notes written by a mourning composer looking back on lost halcyon days that conveys as much the joy of that lost era as it does the author’s present sorrow over losing them. Recommended.

Studio/company: Discotek Media

Available: Now

Rating: Not Rated

This story appears in the Fall 2018 issue of Anime USA Magazine. Click here to get a print copy.