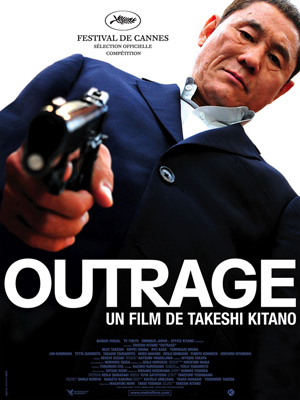

There was a lot of laughter in the audience at the Japan Society during “Beat” Takeshi Kitano’s vicious yakuza murder-thon Outrage. This was no giggling multiplex crowd, nor were we laughing from sheer discomfort (okay, maybe a little bit) over the film’s constant, brutal killings. Outrage is simply a film as cruelly funny as it is bleak, and as I walked out of the theater I was not one hundred percent sure if Kitano was messing with me or not.

There was a lot of laughter in the audience at the Japan Society during “Beat” Takeshi Kitano’s vicious yakuza murder-thon Outrage. This was no giggling multiplex crowd, nor were we laughing from sheer discomfort (okay, maybe a little bit) over the film’s constant, brutal killings. Outrage is simply a film as cruelly funny as it is bleak, and as I walked out of the theater I was not one hundred percent sure if Kitano was messing with me or not.

He’s a comedian, too, you know: this is the guy who gave us Takeshi’s Castle (which was later stolen wholesale by the “creators” of the wildly successful Wipeout). If you’ve never seen either show, they are factories which take certain vital components—moats, rubber-and-foam obstacles, and puny human beings—and produce pain, humiliation, and laughs. More than once during Outrage, I remembered Takeshi’s Castle and felt like I was watching contestants stuck in an unwinnable game hurtle towards death. And I laughed. Hell, I guffawed.

Beat casts himself (he also wrote, directed, and edited) as a yakuza middle-manager who finds himself both caught in a twisted web of family infighting and obligated to do the dirtiest work that the feud entails. Rising tensions among the yakuza around and above Kitano eventually mean that the walls of the system close in on him and his squad. Of course, the irony of it all is that by the yakuza standard, Kitano and his guys were good, faithful gangsters who did nothing more than the work that their superiors specifically asked them to.

While hardly sympathetic (though he attempts to take care of his own, he’s as much a monster as anybody else in the film) Kitano’s character recalls any long-suffering first world desk jockey. He does everything that he’s told to without a second thought out of honor and obligation, and yet the “father” at the top really couldn’t care less about the fealty and code of honor he espouses: rather, he continues to use those lies to manipulate and degrade him until he’s worn out past his usefulness. Kitano uses the well-worn, unsympathetic yakuza as a device to present a fully nihilistic worldview, and he takes care to do so without any emotional attachment whatsoever.

One even picks up a little bitterness from Kitano himself about his own place and the younger generation: his old-fashioned yakuza is described a few times as obsolete, and a geeky young man at a ramen shop, obliviously immersed in a DSi, is served a plate of ramen containing freshly sliced human fingers in a nasty throwaway gag.

One even picks up a little bitterness from Kitano himself about his own place and the younger generation: his old-fashioned yakuza is described a few times as obsolete, and a geeky young man at a ramen shop, obliviously immersed in a DSi, is served a plate of ramen containing freshly sliced human fingers in a nasty throwaway gag.

The many players in this story are mostly forgettable, disposable presences—I’m hard pressed to even remember most of their names—and Kitano’s direction of the extreme violence they partake in is as reserved and detached as the look on his protagonist’s face when he guns down a sauna full of rival gangsters. The camera doesn’t look away because it wants to shield us from the violence: it looks away because it doesn’t really care enough to wallow in it.

There isn’t a scrape of sentiment, passion, or hope here: as in Beat’s fiendish Nintendo game/practical joke on children Takeshi’s Challenge, the system is simply broken. Everybody involved with it (even if you’re just someone’s girlfriend) is doomed to some horrific, disgraceful death. There is no poetic justice and no karma. No reward is waiting at the end of the road. That’s just the way things are. The titular “outrage” is life itself. And that’s part of the comedy!

While the film is as dark, violent, and hopeless as anything could be, Kitano understands how closely comedy and tragedy lie. He never fails to find a dry, cynical punchline in every plot twist and undignified death, and his comic timing—the film’s biggest laugh followed immediately after its most viscerally upsetting scene of violence, an unfortunate dental “accident”—is unmistakable. The audience burst out laughing not only at the grisly violence, but at the absurd, comic irony of the plot twists. The universe is so cruel to Kitano’s character– and crueler still to others– that if you don’t laugh, well, there’s only despair left over.