Naota’s got it rough. Robots and aliens and laser guns, the usual anime protagonist fare. That’s all there, front and center, but he’s got other problems. Nobody wants to pay attention to him. Nobody gives him any credit. He’s smarter than every adult around him. While the grown-ups

caterwaul and prance around, he just wishes everyone would calm down and act their age. His brother’s moved away. He’s a sad grade-schooler. Nobody understands him. He’s lonely, though he’d never admit it. We can’t empathize with robots; loneliness we understand.

.jpg)

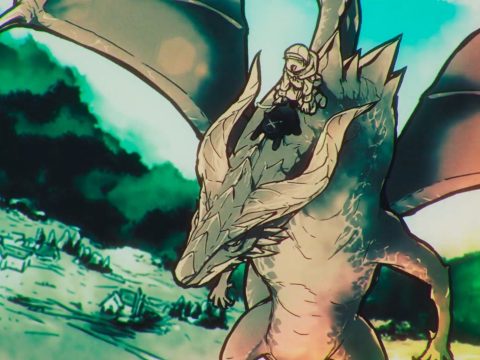

FLCL is anime’s answer to the bildungsroman. It’s a coming-of-age story. It’s the story of Naota’s rejection by, struggle with, and eventual acceptance of society. Naota’s loss of his brother doesn’t set him on a journey, instead the journey is brought to him. Aliens. Robots. Space.

FLCL is also a tiny thing, nestled between bigger shows like Neon Genesis Evangelion and Gurren Lagaan, produced by animation powerhouses Gainax and Production I.G. FLCL is directed by Kazuya Tsurumaki, protégé of Evangelion’s Hideaki Anno. Tsurumaki has been quiet recently, but at the time of FLCL he was riding high on the wave of big-ticket numbers like End of Evangelion. Then there was a brief stopover at Kare Kano, a more subdued story. It’s easy to see where the roots of both the giant robots and the sensitive, personal side of FLCL spring from. All the components were there in Gainax’s earlier works, just waiting for someone to combine them.

While we can’t relate to the fantastical events of FLCL, we understand how foreign and frightening the adult world can seem when you’re 12 years old. We’ve all been the kid who thinks he’s smarter than everyone else. We’ve all wanted everyone to shut up and start respecting us. A robot never held us in mortal peril, but the principles are the same. At some point, we were a left out little kid. We got a punishment we didn’t deserve. We were in our older brother’s shadow. We hated being around our parents. We had our first crush.

Naota’s a kid. A normal, surly, 12-year-old. He thinks he knows everything. He hates his quiet town. “Nothing amazing happens here” is his constant refrain. He hates his father, the immature lech who embarrasses him more often that not. He’s convinced of his town’s boring nature until the bitter end. A robot appears at the end of the first episode and he still thinks it’s uneventful. He meets a space alien with pink hair named Haruko Haruhara. She hits him on the head with a bass guitar, which spurs the growth of a horn in the middle of his forehead. As expected, that horn appears at the most inopportune times. I went through puberty. I remember what that’s like. Although I don’t remember the part where my “horn” was a portal for evil alien robots. I also never met a pink-haired girl while I was in gradeschool. More’s the pity.

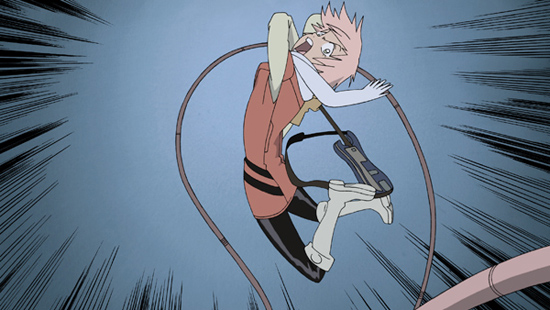

It’s full of fast cuts, references to every cartoon ever made, and tangential discussions during frenzied dialogue that seems to have nothing to do with anything. There are giant robots shaped like hands that wear ponchos and cowboy hats and fire lever action rifles. It’s ridiculous. So what? A comedy show can make us think. Maybe your average anime can’t, but that’s what makes FLCL special. And that’s why everyone should watch it. They owe it to themselves to find a show that understands them, created by people who probably felt the same way at that age. Ostracized, helpless, angry at the world.

Naota doesn’t want to be understood. He’s happier being alone. He’s a kid. He’s too young to be self-reflective. He doesn’t understand what he’s going through, no matter how much he thinks he does. That’s why it’s amazing to watch him grow. There’s more character development in these six episodes than there is in most two-season shows. Couched among the dick and fart jokes is a genuine story about self-respect, and standing up for yourself, and all those other things that we all wish we’d known about when we were little kids. We understand him and that’s why, when he finally seizes the reins of his life, the big victory isn’t killing a space alien. The big victory is claiming his identity. It’s demanding his brother’s ex-girlfriend to stop using him as a stand-in for her lost love. That moment, on the back of a monster laying waste to the city, holds all the bravery and actualization we wish we had as kids. And we just want to cheer him on, because we were all there too.

That’s why FLCL is a great show, because it’s about this kid figuring out what he wants, because it’s about another kid going through a tough time with his dad. A coming-of-age story isn’t just about growing as a person, it’s about realizing that while society was wrong, you were wrong too, and there’s a way to make all the pieces fit together. Naota realizes that, hey, maybe everything isn’t as bad as he makes it out to be, and when he says “nothing amazing happens here” one last time, it’s missing his usual acidic tone.

.jpg)

Some people like this show for the wrong reasons. People love boob jokes and silly dances. You’re allowed to like them, too. But while you laugh, think about what they’re trying to say. This show indicts scummy, weird anime as much as it embraces it. They say “hey, it’s okay to be ridiculous once in a while.” They have to say that, because nothing where a robot pops out of a boy’s forehead could be anything but ridiculous. It’s the rare show, though, that takes it one step further. They take all those poop jokes and dick jokes and giant robot battles, and they make them about something. It’s adolescent. It’s shlocky. It has to be. That’s what little kids are. But that’s not all that they are.

FLCL was out of print and difficult to find for a few years. If you missed your first chance at buying it, make absolutely sure you don’t make the same mistake twice. FLCL is amazing. This is the best of what anime has to give. Not always maudlin, not always goofy, it’s just … Furi Kuri. It’s anything and everything. It’s whatever you need at the time. It’s a story about who we were then and a story for who we are now. It has many imitators. Many shows tried to capitalize on its madcap style. Gainax made Magical Shopping Arcade Abenobashi, and Hiroyuki Imaishi of Production I.G., the man responsible for the frantic “manga panel”scenes of FLCL, would go on to direct Dead Leaves. Neither of those shows, nor the many others, have recaptured the lightning-in-a-bottle feeling of FLCL. They don’t make something like this every day. Watch it now before it’s gone again.

Related Stories:

– Gainax Opens Museum, Studio in Fukushima

– First Evangelion in Ages is a Hikaru Utada Music Video

– Diebuster: Let’s Go Topless

– Opening Up Gainax’s Medaka Box

– The good, the bad and the ugly of 2013