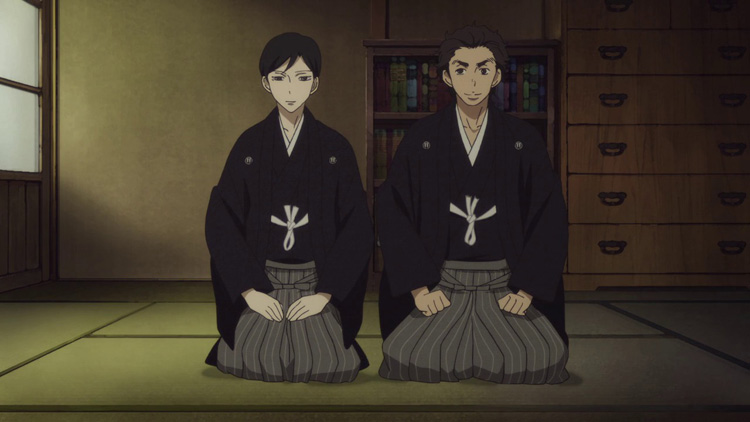

This winter sees the return of the beautiful and tragic Showa Genroku Rakugo Shinjū in its second season following Kikuhiko’s tutelage of Yotaro. While the series itself is a great introduction to the art of rakugo, some fans may have found themselves wanting to delve deeper into its origins and forms. To that end, here’s our primer to the Japanese storytelling art of rakugo.

What is rakugo?

Rakugo is traditional storytelling of humorous stories developed in Edo Period (1603–1868) Japan. The art form began amongst commoners and has continued that way until today. Rakugo, meaning “fallen words,” is told by a single storyteller who performs all roles of the story – male, female, young, old, and even ghosts. There are various types of stories told in rakugo – from ghost stories to musical pieces – where each narrative contains its own type of humor guaranteed to appeal to the everyday folks in the audience.

While every piece of rakugo is different from the last, each story contains an ochi (or “drop”) that serves as the punchline that defines each performance. The Japanese character for ochi is also read “raku” – hence the name rakugo.

History of Rakugo

Though the roots of rakugo can be traced all the way back to monks in the 9th and 10th centuries, the modern form emerged in the Edo Period. Originally performed in the streets, rakugo moved indoors with the invention of the yose, theaters built especially for the artform. Many of these theaters, featured heavily in Showa Genroku Rakugo Shinjū, still exist and can be found scattered throughout Tokyo and Osaka.

Rakugo as it is celebrated today and presented in the anime became extremely popular in the Showa Period (1926-1989). Unfortunately, much of Japan’s art came to a halt with the horrors of World War II. But with postwar peace, a booming working class, and the technological advances of radio and television, rakugo had an astounding resurgence during the 1950s and 60s. Rakugo served as a way to balance the old with the new, and to help find some humor in the postwar era.

Rakugo as Theatre

Created as a form of theater for the common people, rakugo has been described as traditional Japanese standup comedy. Every story begins not with the main narrative, but with a small, humorous tidbit about the storyteller’s life in the modern world. Eventually, the storyteller will relate his personal tale seamlessly into his featured story of the day. That, of course, is followed by the ochi as the punchline to tie it all together.

Unlike the elaborate masks of noh or fantastic sets of kabuki, rakugo exists in a realm of simplicity. The only props available to the storyteller (called the rakugoka) are his paper fan, a small cloth, and his voice. Rakugo stories usually have up to two characters and a narrator. However, it is not rare to find stories with five or six different characters interacting at a time. Zenza, the first rank of storytellers, usually will not take on such complicated stories. The following rank, futatsume, begin to expand on the complicated stories as well as find their own style. Finally, the top-ranked shinuchi storytellers are considered masters who can take on their own students. The ability to create distinct voices for each character and the narrator is the true mark of a rakugo master.

Rakugo Schools

There are two main schools of rakugo storytelling, based in Japan’s two largest cities, Tokyo and Osaka. While the format is virtually the same, and the stories are shared, there are some key differences. Osaka rakugoka use a small table, on which they bang wooden blocks to signal the beginning or scene change of a story. Osaka performers also announce which story they will be performing days or weeks in advance, whereas Tokyo rakugoka keep their selections a secret. Apparently this difference has its origins in Edo-period Tokyo being filled with samurai: Tokyo rakugoka had to check to see if there were any samurai in the audience before choosing a story that poked fun at them (they did have swords, after all!).

“Shinigami”

“Shinigami,” or “Death God,” is probably one of the most famous rakugo stories existing. It is also the main inspiration for Showa Genroku Rakugo Shinjū.

Written by the notable author and rakugoka Sanyutei Encho, “Shinigami” is the tale of a lazy man who must make money quick or end his life, but accidentally summons a shinigami instead. Bound to the man, the Shinigami helps him make money as a way to barter for his freedom. The shinigami tells the man that he can see a person’s lifespan measured on candles, and those with too much luck burn out their candles more quickly. Unconcerned, the man becomes a false doctor using the shinigami’s ability to see if a person is on their deathbed or not to make lots of money. In the end, the shinigami tricks the man into following him to a room filled with people’s candles, showing him that his own candle is nearly out because of his deceitful practices. He tells the man that if he can transfer his candle to another, he will be spared. But the man drops his own candle and dies.

While the story itself sounds rather morbid, it is the humor of the storytelling and dialogue which makes this such a phenomenal tale. Fans of Showa Genroku Rakugo Shinjū may find themselves asking if Kikuhiko the man or the shinigami himself…

Rakugo in English

If you want to get a taste of rakugo in English, check out Katsura Kaishi, the king of English rakugo, or Diane Kichijitsu, a woman from Liverpool who has been studying rakugo in Japan since 1996.

We hope this brief primer helps you have a better understanding of the art behind Showa Genroku Rakugo Shinjū.

![[Primer] An Ensign’s First Guide to Kantai Collection [Primer] An Ensign’s First Guide to Kantai Collection](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/kancolleprimerthumb.jpg)