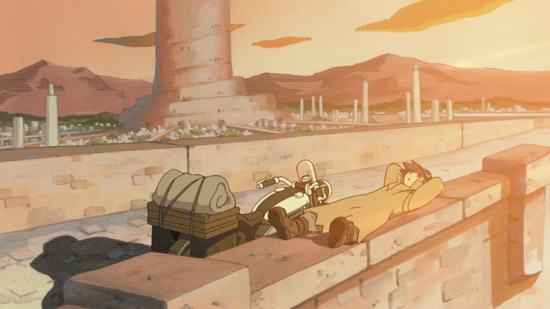

Don’t let Emerson’s “Life is a journey, not a destination” fool you. Sometimes, destinations can be their own journeys. Take, for instance, Kino (a perpetual traveler) and Hermes (an AI-imbued, talking motorcycle), who stay no longer than three days in any country they happen upon. During that time, Kino’s journey mainly consists of exploring the local geographical area as well as the hearts of its people and experiencing (for better and worse) their customs. Moving from country to country like this keeps Kino from settling down, thus retaining her title as a traveler, and ensures a meaningful journey measured in observations as well as the kilometers between them.

Kino’s Journey (Kino no Tabi), which adapts a light novel series by author and noted motorcycle enthusiast Keiichi Sigsawa, poses and stays true to one mantra: “The world is not beautiful, therefore it is.” By repeatedly putting Kino in the role of a stranger in a strange land and presenting a series of emotional, social, and physical conflicts, this series captures the naked essence of an all-too-familiar humanity, despite the fictional landscapes and exaggerated personalities/cultures, for the true observer (the viewer) to appreciate and learn from. The situations Kino experiences range from lighthearted to life threatening, and thankfully no tale is ever a one-note affair regarding tone or character. The same goes for Kino.

Viewers get to spend three episodes getting to know who Kino is before getting to know who Kino was, and Kino’s origin story, as ultimately dark as it is initially adorable and ultimately allegorical, reflects the author’s reverence for those who experience joy, sorrow, and everything in-between as the very definition of the way to live. This underlying philosophy is all the more apparent in Kino’s respect for life as well as the beauty of its transience, imperfection, and emotional intensity. Add in Kino’s sense of detachment, and the natural way this anime unfolds its moral lessons and their ambiguities must be applauded.

Self-contained episodes, ranging from 15 to 30 minutes, might seem too short for such world building, but director Ryutaro Nakamura’s patient pacing, with its balance of reflective observation and action, makes each episode legitimately fulfilling (emotionally, narratively) in regard to individually showcased countries as well as the overall journey. Equally satisfying is how the time period in which Kino’s Journey is set actually condones anachronisms. For example, there are robots in one country and mages in another but no cellular telephones or Internet. It is that sense of long-range disconnect that fosters belief in how different the values and aesthetics of each country Kino visits can be.

Aesthetically, Kino’s Journey is instantly recognizable if for only one aspect: scanlines. This visual effect, applied by Nakamura, produces the feel of watching the series on a tube-based television, and the result is charming … once you get used to it. This visual choice imparts an old-timey feel that fits in perfectly with the world of Kino. Underneath the filter, the art itself is simplistically beautiful. (Try to stop your jaw from dropping upon seeing the fish hook moon in “The Sad Land.”) Even scenes of violence are artfully handled—graphic in necessity, as in the skinning of a rabbit for dinner between countries, or artful in gore (blood plumes and globules). And while the most memorable character designs border on abstract, great attention to facial expressions—especially Kino’s perfect smirk—brings the cast to life.

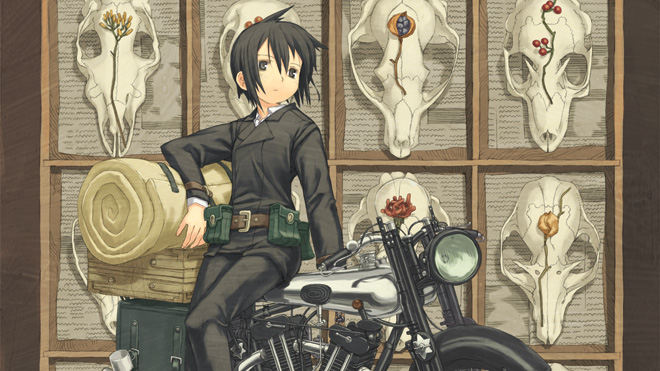

Similarly, Kelli Cousins does a wonderful job in relaying the subtleties and strength inherent in Kino’s soft-spoken dialogue in the English dub. This plays well to the traveler’s androgynous character design; Kino’s trademark cool is short hair, motorcycle goggles, an oversized trench coat, a couple of pistols (and an armory of knives), and a confident, nonchalant, almost debonair air. While Cousins comes across a little more feminine, Ai Maeda seems to be less easily distinguishable. Both serve and suit the character perfectly. Cynthia Martinez’s Hermes, on the other hand, sounds like a robot with a smashed larynx or the tin-bowled Aaron Dismuke (Ed in the Fullmetal Alchemist dub) under the influences of a wicked cold or puberty, while Ryuji Aigase sounds similarly youthful but is much easier on the ears.

What’s spoken is important, of course, but what goes unspoken and the silences that carry those moments are equally important (if not more so). That said, the ADR work is admirable, especially with such episodes as “The Sad Land,” which keeps the heart of the poetry and necessary silences intact while providing dramatic localization, and the timing in the discourse between Kino and Hermes is tops. Opposed to dub, script occasionally tells too much via its own ambition in a series that, unlike most anime, shows instead of telling a lot of seemingly trivial moments that end up being the core of character exploration. In the moments without dialogue, there’s only the background music and sound effects. There are a couple of themes that repeat with variations depending on the mood at hand, and these fit the show so well that you might hardly realize you’re hearing them.

Because its episodes are largely self-contained, Kino’s Journey is one of those rare anime gems that can sit, infinitely ready for a sporadic rewatch (in whole or part), on anyone’s media rack. Whether you visit one country or a few, the journey’s always worth it. And there’s more out there to discover! This collection contains Episodes 1-13, but two more episodes are out there: a prequel in which we discover how Kino trained to be a traveler, and another country-centric tale. As good now as it was when it was originally released in 2003, the series reflects the human condition so accurately that it is not one to leave the heart easily. I cannot recommend this series highly enough.

Kino’s Journey is available from Sentai

Filmworks.