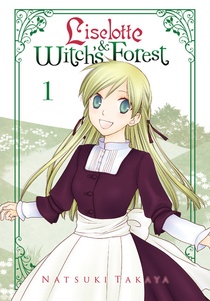

After a series of unfortunate events, the young noblewoman Liselotte is exiled to a faraway land, “east of the east of the east.” Liselotte lives in a little house two days’ walk from the nearest town with her last two faithful servants, Alto and Anna, a twin brother and sister, who keep the household spick and span. As plucky as she is beautiful, Liselotte tries to keep everyone’s spirits up by planting a vegetable garden (or maybe a flower garden?), and as the days drift by, her companions tell her spooky stories of the witches that are said to live in the nearby woods.

One day, Liselotte actually meets a witch, and she’s saved from an awful fate by the appearance of Engetsu, a mysterious, beautiful man with white hair and crimson eyes. Alton is suspicious of the quiet new arrival, but Liselotte is struck by his resemblance to Enrich, a man she once knew. Engetsu joins the household, helping with various problems, such as the appearance of Yomi, a tiny, cute, cat-eared witch’s familiar. “Listen, peons! I’m going to coat this home with each and every witch’s calamity!” Yomi threatens, but his “curses” turn out to be nothing worse than playing in the clean laundry or putting pebbles in their shoes. (“Are you scared? You’ll see! You’ll weep and tremble in fear!”)

Between rambunctious spirits and mysterious men, the house gets a little less lonely, but there’s still a sadness underlying all their time in the forest. “Surely there is something else you should be doing? Do you intend to die here?” Alto asks Liselotte in an unguarded moment. Liselotte answers him firmly: “I came here neither to die nor to rot away. I came here to live.”

A gossamer-light yet surprisingly emotionally affecting fantasy story, Liselotte & Witch’s Forest is all about the unspoken things: the reason Liselotte was exiled, the story of Enrich and Engetsu, the  doom that awaits Liselotte when the witch offers her an apple and she starts to fall into an apple-filled well of darkness. Like in Natsuki Takaya’s best-known work Fruits Basket, the core theme is loneliness and the friendships and loves that challenge that loneliness, in this case in a house in the middle of Fantasy Nowhere rather than in the typical Japanese high school setting. But Liselotte is a more mature work than Fruits Basket, more controlled in its mood (unlike Fruits Basket’s mix of romantic comedy, suicidal thoughts, and eyeball gougings), better drawn (in Takaya’s simple style) and more evocative. Quiet and understated, it makes you want to stay in that house on the edge of the forest until you find out what brought the heroes there, or at least until the vegetable harvest comes. Recommended.

doom that awaits Liselotte when the witch offers her an apple and she starts to fall into an apple-filled well of darkness. Like in Natsuki Takaya’s best-known work Fruits Basket, the core theme is loneliness and the friendships and loves that challenge that loneliness, in this case in a house in the middle of Fantasy Nowhere rather than in the typical Japanese high school setting. But Liselotte is a more mature work than Fruits Basket, more controlled in its mood (unlike Fruits Basket’s mix of romantic comedy, suicidal thoughts, and eyeball gougings), better drawn (in Takaya’s simple style) and more evocative. Quiet and understated, it makes you want to stay in that house on the edge of the forest until you find out what brought the heroes there, or at least until the vegetable harvest comes. Recommended.

publisher: Yen Press

story and art: Natsui Takaya

rating: 13+

![Yokohama Station SF [Manga Review] Yokohama Station SF [Manga Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Yokohama-Station-SF-v2-crop2-480x360.jpg)

![Manner of Death [Review] Manner of Death [Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/manner-of-death-v2-crop-480x360.jpg)

![Origin [Review] Origin [Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/origin-10-crop-480x360.jpg)

![Lady Oscar: The Rose of Versailles [Anime Review] Lady Oscar: The Rose of Versailles [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/RoV_Vol2_Front_CoverArt_V1-480x360.jpg)

![Kirby Manga Mania [Manga Review] Kirby Manga Mania [Manga Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/kirby-manga-mania-v1-16-9-480x360.jpg)

![Sunday Without God [Anime Review] Sunday Without God [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/sunday-without-god-1-480x360.jpg)