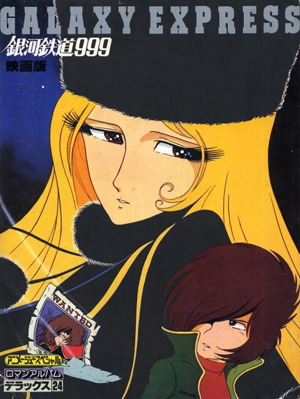

Roman Album book cover for the 1979 Galaxy Express 999 movie. Boffo b.o.!

Roman Album book cover for the 1979 Galaxy Express 999 movie. Boffo b.o.!Call me old-fashioned, nostalgic, or just plain crazy IF YOU WILL, but I just can’t stop thinking about the year 1980 and what it meant to anime, manga, and Japanese pop culture in general. Go to my blog and behold a selection of movie posters, magazine covers, and primordial cosplay from this seminal year. There’s even a picture of me there when I was 7-years old, already possessed by Godzilla, Battle of the Planets and Star Blazers.

Thirty years later, the world is vastly different. It’s faster, more insular… virtual. But from where I sit, the echoes of 1980 keep getting louder and louder all the time. And suddenly, I feel compelled to look back at a time when anime had just gone mainstream in Japan, but was still years away from breaking through to the international market.

A fascinating article by Hank Werba from the June 4th, 1980 issue of Variety, called “Japan’s Animation Boom”, puts everything neatly into perspective. It begins with words that could still be used to draw a sketch of the anime industry today, “Animation in Japan has become a thriving separate community in which the television networks are the heaviest investors, followed by the publishing companies, the major film companies, music-record companies and a growing number of foreign outfits seeking co-production, territorial distribution and ancillary ties with a medium at full momentum.”

A year earlier, an anime film had made history by holding its own against some very stiff foreign competition, and by outgrossing all other Japanese films, live-action included. The article notes, “The box-office champ for 1979 was Galaxy Express 999… on the overall box-office, Galaxy Express 999 placed forth behind ’79 champ Superman and runner-up Death on the Nile and Grease.” By the end of the year, 1980’s Be Forever Yamato would nearly trump The Empire Strikes Back in Japanese theaters for ticket sales.

Poster for 1980’s Doraemon: Nobita’s Dinosaur.

Poster for 1980’s Doraemon: Nobita’s Dinosaur.Numbers like these only hinted at the amount of cash that could be made in the game. And this was the real reason why Variety, America’s show-biz bible, had suddenly taken up an interest in Japanese cartoons. “The film industry investment in Japan animated features is running higher than $25,000,000 and could be closer to $50,000,00.” And this was, of course, peanuts compared to what merchandising stood to bring in. “Japanese trade leaders and reps all agree that merchandising directly related to TV series and features easily topped total investment and revenue… On the strength of these figures, the animation community is well over a trade volume of $500,000,000…”

Variety then peered into its crystal ball and estimated that Japanese animation might someday become a “$1-billion entertainment activity.” They even anticipated that a “breakthrough” of some kind “might materialize in the U.S. through co-production agreements or direct acquisitions.” Surely, this report must have given incentive to any number of guys in Hollywood to buy a ticket to Japan to see if they could get a piece of the action. Meanwhile, the possibility that small groups of foreign fans were already promoting and spreading the gospel of Japanese animation around the globe was not even on the radar yet.

Of course, Variety’s “$1-billion entertainment activity” projection was eventually met and surpassed… although the popularity of anime would come at an incredible price. In April 2010, The Times newspaper obtained a report commissioned by the Japanese Foreign Ministry that claimed that the anime industry was losing was losing $2.4 billion a year to Chinese piracy alone. Such a number “represents more than twice what the Japanese animation industry made from total global exports of cartoons and cartoon-related goods during its best year.”

The burgeoning anime industry of decades past was not without problems as well. In 1979, critic Naoki Togawa told International Film Guide magazine that “successful Japanese animation leans towards escapism with serious productions non-existent… for this reason, it seems too many Japanese films are becoming childish.” Clearly, it was going to take some time before the Japanese cultural elite would take the merits of their own animation seriously.

Your humble EIC in 2010…er, um…1980!

The 1980 Variety article also mentions how the anime boom was creating a divide in Japanese society between a new generation of haves and have-nots. Miyako Ejiri, head of the Arthur Davis Organization (which imported foreign TV and film to Japan and Asia), noted that her six-year old daughter fell under social pressure to consume Doraemon goods “merely to keep her status in class.” Ejiri estimates, for her child’s sake, she spent between $1,000 and $1,200 on Doraemon piggybanks, pencils, necklaces, handbags, etc, during the atomic cat’s 1979-1980 run on TV. Yet compared to all the societal problems that anime has since been blamed for—everything from murder to declining marriage and birth rates—measuring your child’s worth in Doraemon goods seems like getting off easy.

The Variety piece ends on a high note. It sets aside the facts and figures of production costs, return on investment, and the amount of merchandise moved in search of the real reasons for the 1980 anime boom. Legendary Toho-Towa chairman Nagamasa Kawakita gets the final word: “There is no limit to fantasy in this medium and this explains its fascination for children and youth. Comic books and visual stimulus have taken over from books and the cultural establishment, even in the universities. This has become a bridge to the upsurge of animation as an entertainment form.”

In short, anime was the perfect medium for a new generation of fans. For better or worse, history would call them “otaku”.

Patrick Macias is the editor in chief of Otaku USA magazine. His blog can be found online at www.patrickmacias.blogs.com