For many American and international fans of anime and manga, visiting Japan is a dream come true. But because Japan has a very unique culture, how can tourists make sure they’re not accidentally saying or doing the wrong things? Amy’s Guide to Best Behavior in Japan is here to help.

For many American and international fans of anime and manga, visiting Japan is a dream come true. But because Japan has a very unique culture, how can tourists make sure they’re not accidentally saying or doing the wrong things? Amy’s Guide to Best Behavior in Japan is here to help.

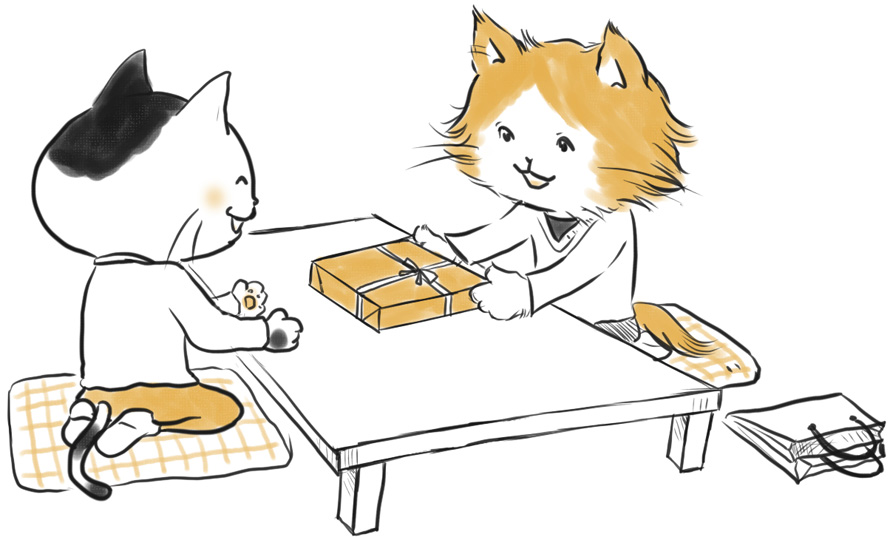

Written by Amy Chavez, and with manga-style illustrations by Jun Hazuki, the book covers everything from how and when to bow, what to do at hotels, restaurants or public baths, and how to be a good guest in a Japanese home. It ends with useful words and phrases. Anyone visiting Japan would want to take this book along with them, and Chavez spoke about the book’s inspiration, how she learned Japanese etiquette as an American living in Japan for the past twenty-five years, and why Otaku USA readers are her ideal audience.

When you first moved to Japan, what were some of the things that stuck out to you most about differences in culture and etiquette?

When I came to Japan, I remember walking down the shōtengai in a shirt that had no sleeves and feeling like, “Wow, I shouldn’t be doing this.” I was teaching at university full-time. Japan has come a long way since then, but still, that attitude about showing your shoulders for older women is that you’re not supposed to do that. I was still young, but I remember that distinctly – feeling out of place. It’s very proper in Japan, and in some ways it’s a dream world, because everyone behaves and no one is rude. And you can really just relax and say, “This is etiquette paradise.” As a foreigner, it’s even better, because you don’t have to follow ALL the rules. You can still walk down the shōtengai and be a 60- or 70-year-old with no sleeves, and that’s fine. But the Japanese would never do that.

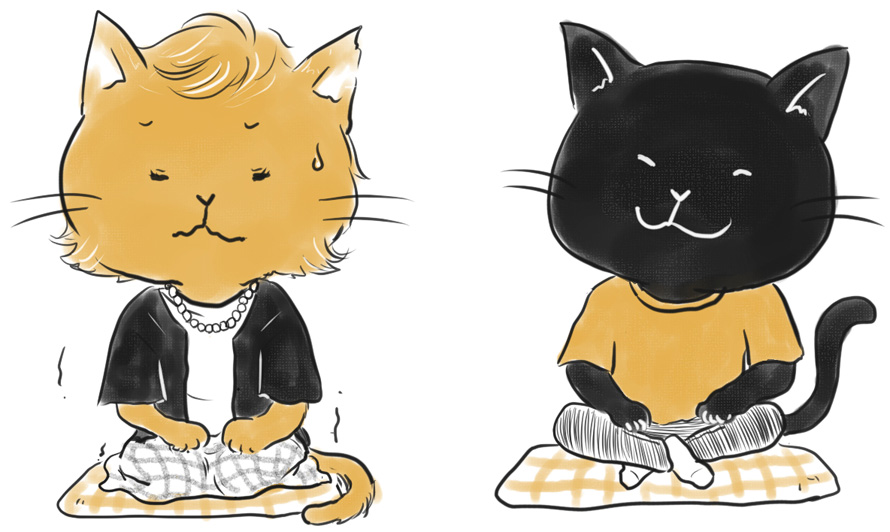

I remember being taught manners just by trial and error when I came to Japan. One of the things was when I went into the university office to meet the president of the university. I sat down and I crossed my legs. The sensei who was responsible for hiring me tapped me on the shoulder. She said, “No, don’t cross your legs.” And then I found out that’s considered rude. But making these faux pas was how I learned.

Many people say to me before coming to Japan, “I don’t want to be rude.” Japan has a reputation, and rightly so, for being a very proper-mannered country, and people don’t want to do something wrong, especially when the rules are so different among cultures about what is polite and not polite. That’s part of what led to this book. People want to know, “What should I not do?” It’s like, “Oh, man, where do I start?”

Why did you decide to write this book?

I live on a small island in the Inland Sea called Shiraishi-jima. It is a tourist island and we have an international villa that only holds ten people. I was in charge of the villa for several years. I also run a beach bar. I’m the only native English speaker on the island so I get a lot of questions. At the same time, I’m helping people with their manners on the island. So I book people, for example, dinners at the local restaurant. The Japanese people are too polite to tell tourists what they shouldn’t be doing — but after the tourists leave, they’ll tell me. So actually the book was born out of this frustration I had. People kept making mistakes and I wanted to tell them they’re making mistakes, but of course you can’t come out and tell someone they’re doing something wrong. And often the burden came back onto me for the behavior of the tourists. And I should clarify that no one thinks the tourists are doing anything wrong on purpose. It’s just that the rules are a little different.

One particularly exasperating evening had me dealing with foreigners who were late for dinner at the restaurant. One showed up at the appointed hour, and that person was waiting for another person who was also staying at the villa, and that person was late. They hadn’t come to the villa together. So there was a big controversy I got pulled into about what they’re supposed to do. Do they go ahead and take the guy’s order who was there? Or do they wait until the other person shows up and take their order? Usually it’s a pretty simple thing, but because it’s an island and they were the only customers, they wanted to make their food at the same time. But the guy wasn’t sure the girl was going to show up at all. The foreigner didn’t speak any Japanese and the restaurant people didn’t speak any English. So then I was called in. Then there was the big question, “Where is the other foreigner? Did something happen to her?”

I ended up having to track down this foreigner, who’d simply been on her way down to the restaurant and some locals had been sitting outside their house and invited her in for a beer. So she was fifteen, twenty minutes late to the dinner — horror of all horrors! But to the Japanese, this was not proper. I was so exasperated by the end of that, having to look all over the island for this girl, find her, put them together, then smooth over the relations. At that point I sent a letter off to Peter Goodman at Stone Bridge Press because we’d been talking about doing a book together but we just couldn’t find the right book. Well, here it was.

Tourism in Japan is just exploding. They’re hoping to have 40 million tourists for 2020. So there is a call now for a book like this that tells people what they should be doing. A few years ago, I would have told people, “Just use common sense and you’ll be fine.” But now there’s so many tourists there’s been a backlash. Some Japanese are complaining about tourists and their behavior. And I think, “Hey, the least we can do as tourists is try to find out what we should or shouldn’t be doing.” You don’t have to participate in all the rules, but if you’re at least aware, it’s a win-win situation for both sides.

How did you decide what details to put in the book?

That was a really long process. In my acknowledgments, I do thank people in certain areas. One was a manager of a Ryokan, one was a CEO of a restaurant chain, people who would deal with tourists all the time. I did surveys. I asked panelists and experts. When I wanted to put the book together, I thought I would just do the things that people definitely wouldn’t know. But the publisher said, “That’s not enough to make a book that’s worth selling.” So we included everything from both sides, not just the tourist side, but the Japanese side of how they wish the tourists were behaving. We started with really basic stuff, like take your shoes off when you enter a house. Even stuff like that you’d think is really basic, but a lot of people don’t know it. Maybe someone’s traveling around the world and Japan is just one of their stops and they’re going to be there a week. They haven’t really done their homework to know this stuff.

In your book you have a few humorous stories about faux pas in Japan. Do you have any others you want to share?

When I first started going to temples and shrines, I did it on the Shikoku Pilgrimage. That’s a six-week hike. Every time I arrived at a temple I’d get out my picnic lunch and eat. It was only after that I learned you’re not supposed to eat on the temple grounds. That embarrassed me.

Why did you decide to include manga-style illustrations in the book?

Because that’s Japan now. Manga, right? We had a couple artists we were thinking of. One was a very well-known artist who doesn’t do manga style. The other is an up-and-coming artist who does manga style. I gave them both to Stone Bridge Press and it was very hard for them to decide. In the end they went with the manga style because it’s more in sync with Japan and tourists right now. A lot of tourists come to Japan because of manga and anime.

What can you tell us about your other writing?

I’ve been a columnist for The Japan Times for over twenty years. For the first fifteen years, I wrote a humor column about living in Japan and the Japanese culture and living on a small, tiny island in the Inland Sea with 500 people. The life here is vastly different from living in Tokyo or any of the big cities.

Then I wrote a book about my Shikoku Pilgrimage experience because I decided to run it. It’s not just about my experience; it’s more about the meaning of the pilgrimage in a way that’s easy for foreigners to understand, especially if they’re going to do the pilgrimage.

Then the book before that was Guidebook to Japan: What the Other Guidebooks Won’t Tell You. That’s just a humorous book about different experiences in Japan.

I was really excited that you contacted me, because Otaku USA is such a good place for this book. The readers of manga and the viewers of anime are much more in tune with Japanese culture than your average tourist who might not know anything about Japan or who might immediately have samurai come to mind. When you read manga, you see these references. You see the Butsudan, the cherry blossoms, you see all the customs. I think that is really the market for this book — people who already have an idea of the culture and really want to make a good impression while they’re here.

——

Danica Davidson, along with Japanese mangaka Rena Saiya, is the author of Manga Art for Intermediates. In addition to showing how to draw manga character types in detail, the book describes how professional Japanese manga creators work, including common techniques and what drawing utensils they use.