Carnivalesque

It seems impossible we’ll ever again witness an anime like 1985’s Robot Carnival. The last great anthology film, Short Peace, went almost entirely ignored. The last great anthology series, Space Dandy, was at best misunderstood, at worst excoriated. Not for its quality, mind: as Jacob Chapman of Anime News Network rightly examined, the problem was less with craftsmanship than with current attitudes toward media consumption: “In a society that ha(s) embraced bingewatching and d(oes) not demand that one episode of a series tell a satisfying story on its own … a series that works best when experienced one episode at a time … (is) not what anime fans … want.”

It seems impossible in this environment, then, that Discotek has released Robot Carnival on Blu-ray at all. Yes, it enjoys a minor reputation as a historical curiosity being that it received a somewhat wide release in American theaters back in the early 90s thanks to Streamline Pictures; yes, there is a trace of producer Katsuhiro Otomo’s thumb print upon it in the blocky cast of many characters’ faces and the loving (nearly obsessive) attention to mechanical detail always on display in every piece here.

But the former fact is a mere footnote, while the latter belies that Robot Carnival is difficult to categorize in ways that seem directly at odds with current viewing habits and storytelling trends. Most of the nine shorts collected here are not only narratively disconnected from each other; they are often so abstract that a viewer with a more rigid sense of structure and characterization might suspect they are disconnected even from themselves. In all but two of the pieces the characters refuse to speak in anything resembling intelligible dialogue; what are presented here are not as often stories as they are music videos, mood pieces, or even tone poems.

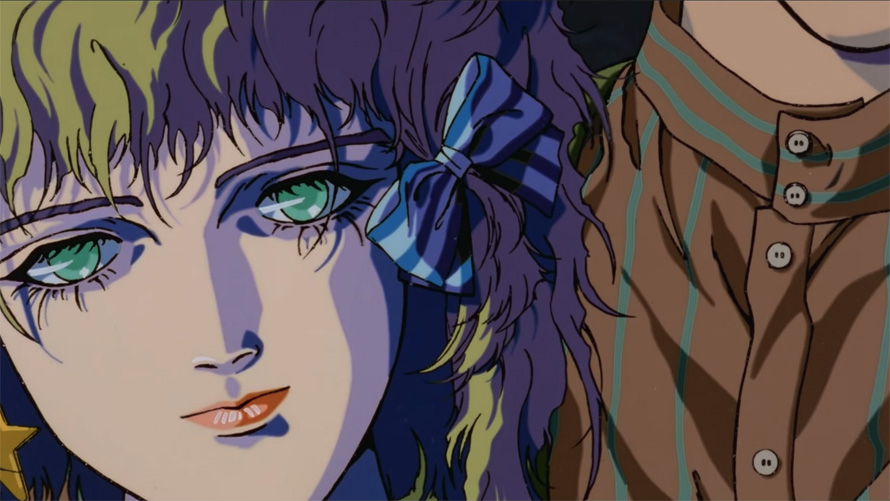

There is little narrative logic driving a segment like “Starlight Angel,” after all, and there doesn’t need to be when it’s more interested in capturing something of the fairy tale romance of the music video for A-ha’s “Take on Me.” “Chicken Man & Red Neck” is at once a tribute to the elemental menace embodied by the “Night on Bald Mountain” segment from Fantasia and an opportunity for director Takashi Nakamura to indulge a love of comically over-animated facial expressions and body language that recalls the work of Don Bluth. Mao Lamdo’s “Cloud” is not even traditionally animated: as the nameless young protagonist trudges head down into blustering winds, the pencil-sketched backgrounds behind him slowly change to impart the illusion of motion and change in a way that feels completely at odds with traditional approaches toward capturing time and movement.

Only Yasuomi Umetsu’s “Presence” opts to tell a straightforward dramatic narrative, yet it is told with such quiet reserve, with such a poetic flourish that it feels more abstract than it truly is. (There is a story at play in “Strange Tales of Meiji Machine Culture” but it’s purely a vehicle for the physical comedy as beautifully conveyed by Hiroyuki Kitakubo’s painstaking attention to minutiae; it’s of no more concern than the plot of “Starlight Angel”). Everywhere here there is a sense that nothing has quite been said.

It would be easy to dismiss Robot Carnival on these grounds as a triumph of style over substance, then. But to write off this or other anthologies as mere technical curiosities is to do them and us all a great disservice. Such collections are reliefs, shelters from a risk-averse industry overrun by workman artists so afraid to violate the basic tenets of visual storytelling they haven’t yet realized these are suggestions, not holy writ. For literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin, anthologies like Robot Carnival—works he described tellingly as “carnivalesque”—were not mere distraction from the events of the day but a relief and even refusal of the status quo. They were works that, though ritual celebration, inverted the structures imposed by tradition and overturned what was acceptable to reveal new modes of storytelling and so new modes of thinking and being.

Robot Carnival may not tell us much of these other modes directly, but even 30 years later it demonstrates through its series of beautiful and beautifully unorthodox styles and methods a number of alternatives to trends that have become aesthetically and spiritually smothering in the last three decades. More than a historical curiosity reminding us of what could have been, it remains a compelling suggestion of what might still be. Recommended.

Studio/company: Discotek Media

Available: Now

Rating: Not Rated

This story appears in the Fall 2018 issue of Anime USA Magazine. Click here to get a print copy.

![Yokohama Station SF [Manga Review] Yokohama Station SF [Manga Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Yokohama-Station-SF-v2-crop2-480x360.jpg)

![Manner of Death [Review] Manner of Death [Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/manner-of-death-v2-crop-480x360.jpg)

![Origin [Review] Origin [Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/origin-10-crop-480x360.jpg)

![Lady Oscar: The Rose of Versailles [Anime Review] Lady Oscar: The Rose of Versailles [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/RoV_Vol2_Front_CoverArt_V1-480x360.jpg)

![SSSS.Dynazenon [Anime Review] SSSS.Dynazenon [Anime Review]](https://otakuusamagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/16-9-SSSS.Dynazenon_Key_Visual_3.5-480x360.jpg)