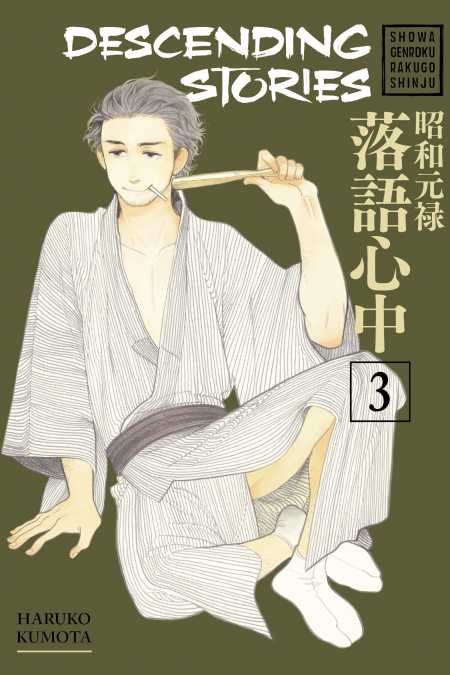

The tragic trajectory of Yakumo’s flashback follow its natural arc in the third volume of Descending Stories as he and adopted brother Sukeroku move beyond their long apprenticeship to define themselves not just as shin’uchi – rakugo performers in their own rights – but as men. Spurred on by Sukeroku’s goading, Yakumo discovers that the adoration of audiences and his ability to command their gaze with his refined performances provided the affirmation he’d been seeking all along, and so transcends the plateau of talent he felt himself stuck on last volume. It’s the catalyst he needs to realize what he has always known subconsciously: that the theater is his home, the rakugo community and his adoring audience his family, and so also proves the catalyst he needs to end his romantic tryst with the geisha Miyokichi, whom he now considers a distraction he cannot afford.

The tragic trajectory of Yakumo’s flashback follow its natural arc in the third volume of Descending Stories as he and adopted brother Sukeroku move beyond their long apprenticeship to define themselves not just as shin’uchi – rakugo performers in their own rights – but as men. Spurred on by Sukeroku’s goading, Yakumo discovers that the adoration of audiences and his ability to command their gaze with his refined performances provided the affirmation he’d been seeking all along, and so transcends the plateau of talent he felt himself stuck on last volume. It’s the catalyst he needs to realize what he has always known subconsciously: that the theater is his home, the rakugo community and his adoring audience his family, and so also proves the catalyst he needs to end his romantic tryst with the geisha Miyokichi, whom he now considers a distraction he cannot afford.

For his part, Sukeroku decides to expand his boisterous and wildly popular approach to the form rather than refine it to match the shibboleths of the stodgy rakugo world. The times, he realizes, are changing irrevocably, and with them so too must their art, lest it be left behind by a post-war world “flooded with the new.” While his teacher, the former Yakumo, insists “Rakugo is something we all protect together. Harmony’s the most important thing,” Sukeroku’s fierce individualism brooks no argument, at least not from attentive readers. We know well from Yakumo’s conversation with Mangetsu in the first volume and his own overtures towards Yotaro about “finding the way forward for rakugo” that even decades later the form remains stultified by its obsession with this communal harmony. That to Yakumo, Yotaro and his irrepressible energy represent what may be the art’s last choice for innovation, and so relevance. Yet if Sukeroku’s vital passions were invaluable to advancing the form, they also estranged him from the former Yakumo and sent him into the arms of the similarly rejected Miyokichi, a coupling destined to bring disaster to the pair and all they love.

It is a predictable story, but that it is predictable shouldn’t be taken for a fault: we gravitate toward tragedies because the inevitably of this misery makes it all the more poignant. What puts us off from the predictable story is not that foreknowledge of events will make them less shocking, no, but the fear that the author should end up trying to manipulate our expectations and knowledge to cover up their own weaknesses like a tin board thrown over a pothole. As a solution it is quick and pragmatic, but every time we hear that tinny thud under our tires and the rumble in our seats we long for a proper fix. It is the same with every story we read that is dramatically functional but, ultimately, cheaply realized: we are only reminded of the absence of a better way. And in Descending Stories this reliance on structural cliches has, sadly, given Kumota something of a free pass when it comes to developing the psychologies of her characters. As I’ve said in previous reviews, her writing style is coarse, broad; finer toned development is generally glossed over in favor of monologues that conveniently explain motives and motivate action. Because she knows we know the story and the character beats, she seems to feel readers will be satisfied by emotional shorthand, and so abbreviates so much of the interaction between characters that is essential not to understanding them, but to caring for them.

Yes, we realize that Miyokichi and Yakumo’s budding romance can only end in misery for all, but this does not mean we should be deprived of seeing it blossom and then wither. It is impossible to take Yakumo at his word when he proclaims leaving Miyokichi was the hardest thing he’s ever done because the few interactions we’ve been allowed to see between them were labored, boring affairs Yakumo seemed to tolerate begrudgingly. Why should we feel anything but his same boredom? Similarly, the relationship between Miyokichi and Sukeroku is thrown together entirely to move the plot forward: their one interaction betrays little chemistry; it consists almost entirely of Miyokichi explaining, didactically, how and why she came to be this way.

It is not that Kumota does not understand these characters enough to invest them with depth. She knows them intimately, a fact that is plain when she writes about their relationship to art, and how they mediate with the world through their craft. The stunned look in Yakumo’s eyes when Sukeroku tells him how to play a crowd tells us more about his revelation of his desires and the heady mix of passion, resentment and love he feels toward his friend (a mix too familiar to anybody who has ever collaborated with a close friend and rival on a long project) than any number of monologues could. And the betrayal Sukeroku feels when the former Yakumo denies him the title in favor of his friend, the man we know as Yakumo, is palpable: how could it be anything else, when this exact point has been carefully built not only through a grand soliloquy earlier, but through subtle interactions, through an implied history, through carefully observed action and speech?

It should be telling that the rakugo sections are always the most impressive section in each volume, that they all reveal as much about the actor performing them as they do about the characters in those plays: Kumota has a deep love of the arts that translates into a deep understanding of the same. Like her characters, it seems to be her best method for understanding the world and herself. What she seems less aware of is how people interact beyond the arts, what should drive those of us who do not define ourselves through their craft; ironically, she seems to view them as nothing but the stock types you would find in the worst kind of art. It’s an odd contradiction and a limitation that, ironically, seems to insure her own work could become as insular a pleasure as rakugo itself if not soon addressed.

Story & Art: Haruko Kumota

Publisher: Kodansha Comics