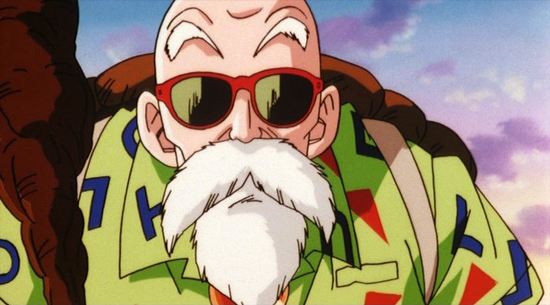

Mike McFarland has been involved with the anime industry a very long time, getting in on the proverbial ground floor as one of the first voice actors Funimation hired for their dub of Dragon Ball Z (as Master Roshi and Yajirobe) back in the mid 1990s. From there, he went on to become a full-fledged voice director involved in every stage of the voice acting process, working to help bring popular shows like Yu Yu Hakusho, Fullmetal Alchemist, and Attack on Titan to a wider audience.

What are some of the challenges involved when dubbing a show into English? How does the original Japanese version effect English-language performances? And just how much of an impact did Cowboy Bebop’s legendary dub have on him and other industry professionals? Read on to find out:

OUSA: You were the Voice Director for Attack on Titan. What were some of the challenges you faced working on that show?

Mike McFarland: There were a lot of them, and they had to be handled very carefully in a very specific way. I wanted to have the proper cast for it, and to me, “proper cast” meant who was right for each individual part. I wasn’t concerned about location, as long as they were experienced and right for the part and I had faith in their abilities as actors.

A lot of the Dallas/Fort Worth actors we work with are fantastic, but for a project like Titan I thought it would be more interesting to mix it up and have a wide array of people on one project who you may not have heard together side by side before.

So there were the logistics of bringing in people from all over the US while still hitting my production deadlines, and still trying to make sure that I had the canon and nuances of the show down and hitting the broadcast and home release deadlines. I recorded over the holidays as well, so I was going through Thanksgiving and Christmas, trying to make sure I had everything I needed while everyone’s availability was limited. Those were some of the challenges I had to deal with.

OUSA: How far away were you bringing actors in from? Did you have any extra leeway to work with since Attack on Titan is such a big property?

McFarland: I think the farthest away I was bringing people in from was LA. I don’t think we had any Vancouver people or anything like that. We had people from Houston, several folks from LA… I don’t think there were any New York folks this time.

It’s not necessarily this particular project. It’s projects that have what I’d call a “typical home release schedule” — this one had a home release and a televised schedule, but they kind of lined up with each other, so I didn’t have to do a big push for one and then sit there for a while before it released on disc.

As long as I have a regular production schedule where I get around 5 or 6 episodes, work on those until they’re wrapped, and then work on the next 5 or 6 until we’re done with the whole series — situations like that leave me with the chance to work on a batch of episodes for 5-6 weeks, which gives me the leeway to be a little more flexible with my cast.

If it’s weekly deadlines, like a broadcast dub where they happen right after the simulcast of the subtitled version in Japan, that’s quite limiting. That gives a lot of the Dallas/Fort Worth people a lot of the work. And once again, they’re great, and I’m so glad that we have so many talented people right there in the metroplex to work on that stuff.

OUSA: You mentioned the challenge involved in getting the canon and nuances of a show down during production. What’s your process for keeping track of that during production?

McFarland: To me, the original track that they did in Japan dictates what I should do. I don’t ever take a show (at least I don’t think I have) that has a certain tone to it and a certain way that the lines are approached and decide to go off the deep end and do something completely different with it.

In some cases that’s the plan. like with a Crayon Shin-chan or a Ghost Stories, and I get that. But when we receive a show and we’re supposed to do a true to translation approach to it, I’ll also take a true to performance take in regards to what the original voice actors and director did.

OUSA: Do you ever, say, play back a recording of the original Japanese line for the English voice actor in the recording booth?

McFarland: Yes. I mean, we preview the lines every time no matter what. I know a few studios here and there just record and record without ever letting the actor hear the original performance. I play the original performances every time no matter what.

If the actor is not quite getting the right nuance or the right emotional context and my direction isn’t helping, I’ll go back and ask them to listen closely to what the original performance is doing, how their voice sits and what they’re doing with it. I’ll tell them we don’t have to do exactly what they’re doing, but the original does capture an emotional moment and some context that — with whatever you’re doing — I’m not hearing. So let’s do it again. That kind of thing.

OUSA: Have you ever run into any sticking points with that approach that required you to take things in a different direction?

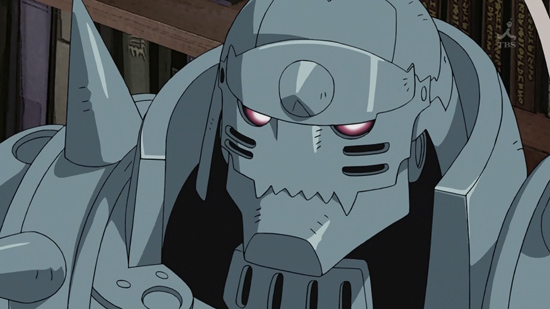

McFarland: Yeah, it depends on the actor and what works best for them. I know in the instance of the first Fullmetal Alchemist, Aaron Dismuke, who played Alphonse, was still… I think he was 10 or 11 years old. So he didn’t have a lot of life experience to draw from that would allow me to make comparisons like, “imagine this,” or “think about how much it hurts when this happens,” and so on. He hadn’t gone through those things, so for some of the emotional stuff, if it wasn’t quite playing right, I had to be a little creative.

In voice acting, the end product is what matters, and getting there doesn’t necessarily matter voice-wise. If it sounds convincingly like you are in a particular emotional state even though you as an actor aren’t actually there, that’s fine. It just needs to sound that way. So with Aaron, for some of the emotional stuff where he’d be talking to his brother, for example, if I couldn’t get the right shakiness in his voice, I’d tell him to pretend to be freezing cold outside with no coat on. And from there we’d have to pull it back because it just sounded like he was freezing, find some kind of middle ground for that, keep that kind of shakiness in your voice, but also play to the fact that this is upsetting. Whatever technical tricks you can work with the actor, whatever works for them to help get you to the place you need to be to tell the story in the proper fashion is what needs to happen.

OUSA: Aaron didn’t reprise that role for Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood, correct?

McFarland: He did not. His voice had dropped significantly by then, so he was unable to play the part of Vic’s younger brother, I thought. So we brought him back as the younger version of Hoenheim during a flashback. I love Aaron, he was my lead in Blood Blockade Battlefront, which I just recently recorded as well. I think he’s a great actor, and it’s always good to work with him.

OUSA: While we’re on the subject, can you talk a little bit about your experience working on Blood Blockade Battlefront?

McFarland: It’s been a lot of fun to work on. It’s an interesting show because it has such a fun, comedic element to it, a very cool modern soundtrack, and the setting is a North American setting, so there’s a lot of things that make it different from the typical anime, or at least the typical anime that I’ve worked on.

The fun element on that show was finding the right actors and voices to really play up that comedy when it’s appropriate, but still be able to stay in character and make the moments believable when things get more serious and lives are at stake.

That’s not always the easiest thing, some specialize in one or the other. It’s the same as on-camera: some actors are very good at being funny and have that gift for it, but when they try to take a comedic role everyone’s like “I don’t want to see it.” Even if they’re completely qualified for it, sometimes the audience doesn’t take to it. And then for the performers, some people are just more comfortable doing drama, and they feel stupid doing comedy.

OUSA: Is there anything you’ve learned over the course of your years of experience in the industry that’s changed how you approach projects now compared to when you were just starting?

McFarland: The only thing that I do now that I didn’t do before — or maybe I should say saw differently before — is… I see mouth movements differently than I did 10, 15 years ago. So when I watch something like Galaxy Railways or the first FMA, or even Trinity Blood, everything looks a little short to me. The lines don’t quite fill out to the end of the mouth movements.

I’ve gotten so used to how I do things now that when I go back and look at older shows that I’ve worked on, I notice that old mindset as far as what fits. The performances are all fine, I’ve got no issue with the performances, and for a lot of people who watch anime and are just looking for the story and the character and the performances, they’re not seeing the same things I am anyway, since I’m looking at things from a production standpoint.

OUSA: Have you been inspired by other voice actors and directors in the industry at all?

McFarland: Not in any specific sense. I started out working on Dragon Ball as either a sub-director or a contract director who would come in from time to time, and when I transitioned to working full time (I think Case Closed was the first thing I was really heavily involved with, followed by Fullmetal Alchemist), I became more interested in seeing what other people were doing.

I looked at what people in California and Houston were doing, and the only thing that really sticks out in my mind is the first time I saw Cowboy Bebop and Wolf’s Rain, and being so impressed with the direction and performances on those shows. It really inspired me.

Dragon Ball and whatever else, that’s a certain type of show, but when you’re working on an FMP or these other types of shows, you really can take it to a beautiful, beautiful place. It’s not just some sort of animated series where people go in to the booth, record all day and take a paycheck. You’re helping to create art, you’re trying to tell an eastern story to a western audience and lose nothing.

You can have a fan from America and a fan from Japan sit down with an interpreter to talk about a show they loved, and not have anything different, no barrier between the two as far as things they heard or witnessed in the show. What became clear to me during that time frame was the responsibility of the director as far as what needs to happen, the professional level and the beautiful level to which it can sound to help that story take place.

OUSA: When you refer to the “beautiful level,” what are you referring to, exactly?

McFarland: To me what that means is… if you’re watching an animated series, and nothing stands out as jarring, and if a character opens their mouth and the tone of their voice and the way that they say something, and the fluidity with which they say something all seems completely normal, like you’re just looking in with a telescope on a world where everyone just happens to be animated. It’s not a cartoon, it’s not anime, you’re just watching a universe from afar that someone has filmed. You’re taking it to a place where that becomes a reality and not just entertainment. At least, that’s how I see it. (laughs)