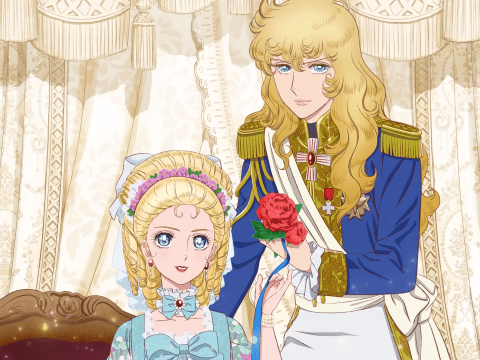

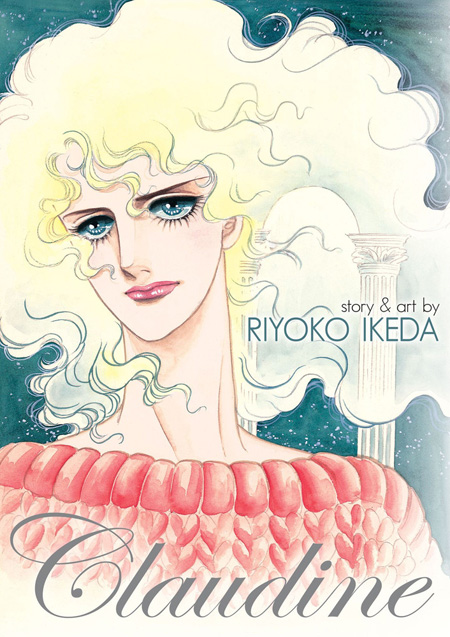

Claudine seems like a missed opportunity on all fronts. Author and artist Riyoko Ikeda is one of the most important manga creators of the latter half of the 20th century; few titles can claim the level of influence and the critical acclaim her 1970s classic The Rose of Versailles enjoys, and few of her peers can claim to have been as narratively challenging and unconventional as she was at her peak. Little of her work has been released in America until now. Yet when given the chance to finally introduce English-reading audiences to the kind of meticulously researched, gorgeously rendered, and thematically daring period melodramas she’s known for, publisher Seven Seas opted not to translate Rose of Versailles or the similarly ambitious The Window of Orpheus, but the middling, ill-considered Claudine.

In some respects the choice is understandable, given that Versailles and Orpheus are grandiose narratives over a dozen volumes in length while Claudine is a slim volume barely 100 pages long. It’s a safe level of commitment: if the volume fails it’s a meager investment for publisher and readers alike, and if it succeeds it establishes a foundation from which to launch the rest of Ikeda’s oeuvre. But it’s difficult to see Claudine doing anything to win over today’s manga readers or to convince skeptics that Ikeda deserves her storied reputation. The emotional and intellectual content of Claudine are as slim as its page count.

In some respects the choice is understandable, given that Versailles and Orpheus are grandiose narratives over a dozen volumes in length while Claudine is a slim volume barely 100 pages long. It’s a safe level of commitment: if the volume fails it’s a meager investment for publisher and readers alike, and if it succeeds it establishes a foundation from which to launch the rest of Ikeda’s oeuvre. But it’s difficult to see Claudine doing anything to win over today’s manga readers or to convince skeptics that Ikeda deserves her storied reputation. The emotional and intellectual content of Claudine are as slim as its page count.

Certainly one could be fooled into thinking there’s heft to Claudine based on the synopsis: a young French aristocrat realizes early that while he was born a woman he identifies as a man. It’s a narrative rife with opportunities to explore how society constructs gender, how gender roles are reflected through the prism of sex, and how modern ideas of LGBT identity clash against the culture of late 18th-century France. The setup promises much but does little to deliver. Claudine’s mother and a potential love interest might fret about his sexual identification, but his father dotes on him in all ways, the doctor he’s sent to for evaluation is nothing but supportive, and his brothers accept his identification without incident. For members of the aristocracy at a time not exactly known for enlightened views on gender, they are exceptionally understanding.

Nor is Claudine daunted by his mother’s prejudice, or indeed given to any kind of doubt. From the age of eight he’s confident in his identity, freeing the story from either external or internal conflict. The majority of the plot stems less from prejudice or identity than from the kind of oldfashioned melodramatic misunderstandings and manipulations that have plagued the protagonists of tragic love stories throughout history. Too often, Claudine’s unique circumstances seem entirely beside the point.

There are intriguing moments, such as the fact that the characters most accepting of Claudine’s identity are his two greatest antagonists, a jealous would-be lover and a  tutor who is suggested to have a same-sex romantic connection to Claudine’s father. The idea that Claudine’s father might be so accepting of his son because he himself has homosexual feelings could have been explored to give more depth to a character who is portrayed only as a kind of saint. But Ikeda’s signature gorgeous, baroque art covers up any murkiess or complexity in Claudine’s world.

tutor who is suggested to have a same-sex romantic connection to Claudine’s father. The idea that Claudine’s father might be so accepting of his son because he himself has homosexual feelings could have been explored to give more depth to a character who is portrayed only as a kind of saint. But Ikeda’s signature gorgeous, baroque art covers up any murkiess or complexity in Claudine’s world.

With the manga’s short length, there’s no time for Ikeda to delve into the premise, to develop the historical setting and the ways it might affect the characters. The book reads like the Cliff Notes to a more fully fleshed graphic novel that was never made. Characters come and go before they’ve properly introduced themselves, emotional arcs are established, briefly discussed, and then resolved in a handful of pages, and nobody stops long enough to reflect on why any of the events unfold the way they do. The characters are hardly characters and the world they inhabit is hardly a world, despite Ikeda’s elaborate art, expressive character designs, and cinematic panel arrangements. Ikeda hardly seems interested in Claudine’s story or problems. Why, then, should audiences be?

publisher: Seven Seas

story and art: Riyoko Ikeda

rating: T

This story appears in the October 2018 issue of Otaku USA Magazine. Click here to get a print copy.