[Excerpted from the December 2007 issue of Otaku USA magazine

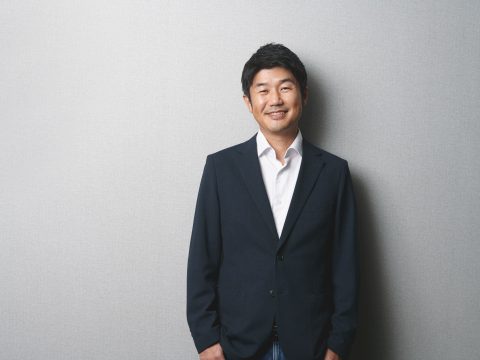

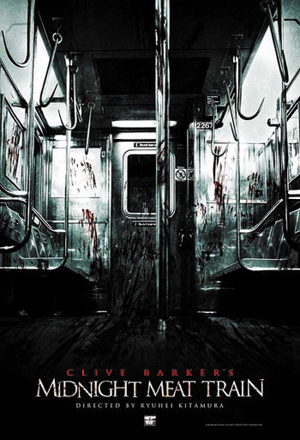

Ryuhei Kitamura is a giant among Japanese film directors. The only catch is, he’s not in Japan anymore. A newly minted Los Angelino, Kitamura is currently prepping his US film debut with Midnight Meat Train, an adaptation of the gruesome Clive Barker story of the same name, set for release next spring.

Born in Osaka in 1969, Kitamura, a self-described “movie otaku”, left high school at the age of 17 to follow his Mad Max-inspired dreams of becoming a director by studying at the School of Visual Arts in Australia. Upon returning to Japan, Kitamura hit a home run with his independently produced Versus (2000, available from Media Blasters), a stunning mix of zombie horror, gunplay, comedy, and kung fu that won instant acclaim around the world. Now a hot property, Kitamura was tapped to helm the manga-inspired big-budget action films Azumi (Media Blasters) and Sky High (ADV Films). Both released in 2003, the former was one of the highest grossing movies of the year in Japan. Kitamura had his pick of options and began eyeing projects in Hollywood. Meanwhile, Toho Studios sized up Kitamura to helm Godzilla Final Wars (Sony Pictures), their 50th-anniversary celebration, and so-called “final” film of the Godzilla series. But the experience of making the 2004 epic, which has both fans and detractors, soured Kitamura on the Japanese studio system for good. After delivering one more independent production with the wild action-comedy LOVEDEATH (2006) Kitamura finally made the move to Tinseltown and got onboard the Midnight Meat Train.

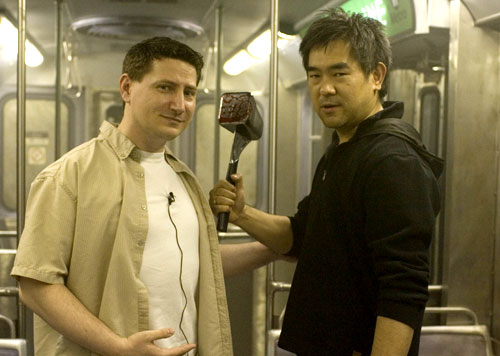

When we caught up with Ryuhei in mid-August, he was busy editing his new film and setting up a multitude of new projects elsewhere. He’d also just gotten back from the San Diego Comic Con and Otakon in Baltimore. It seemed like a good time to ask the always outspoken and refreshingly honest film director��

PATRICK MACIAS: How was the San Diego Comic Con this year?

RYUHEI KITAMURA: Comic Con was fun. I went there last year because my movie Azumi was finally coming out in the States. I’d been trying hard to find the right project to make my first Hollywood movie for, like, the last three or four years and all my agents and people did was send me scripts for boring sequels or B-horror movies or things like that. So I read something like 60 scripts in a few years and I kept saying “no, no, no,” and my agent kept saying, “Why don’t you want to do this?” I kept telling them to “send me something good” and they didn’t , so I had to leave them. So exactly a year ago, I was free and I had nobody representing me. Then I went to Comic Con.

My friend was working on Afro Samurai and we were having dinner together and he said, “[Afro Samurai voice actor) Samuel L. Jackson is in San Diego at a party and I want to introduce you to him.” I said, “No, don’t do it.” I didn’t just want to meet him and say, “I’m a big fan of yours,” but what else am I going to say? But my friend called Sam Jackson’s manager anyway and left a message. When the manager called back she asked, “Is your friend the guy who directed Versus (2000) and Azumi (2003)?” So I went to the party and it turned out that Sam Jackson was a big fan of mine. He’d watched the uncut DVDs of those films over and over. He said, “We got to do something together. Who represents you?” And I told him, “Nobody, I just fired everyone.” He introduced me to his manager and told her, “You’ve got to watch this man’s movies. He’s amazing.” So she watched my movies and called me and she’s my manager now. So it was like I’d just left everybody with no plan, and after three days … I dunno, it was like fate. I met her only twice before I had to go back to Japan to work on LOVEDEATH (2006). But at the end of September last year, I came back to the States because I’m a big fan of the 80s rock band Asia and they were doing a reunion tour with all the original members after 23 years so it was a big deal.

Oh yeah, Asia! They did “Heat of the Moment” and “Only Time Will Tell”…

I’m a big fan of those progressive rock bands. That’s why when I did Godzilla Final Wars (2004) I asked Keith Emerson (from Emerson, Lake, and Palmer) to do the music. So Asia was in Vegas and I followed them there. I called my new agent and told her I’d be back in LA for another show so there was a little time to set up some meetings before I went back to Japan. The first meeting she set up was with Lakeshore Entertainment and I met with producer Gary Lucchesi and we talked and it felt good. Gary said, “I really want to work with you and we have this project called The Midnight Meat Train. Have you heard of it?” I was like, “Wow!” Of course I knew it. It’s a story in the first Clive Barker book that came out in Japan in 1987. I bought it on the day it came out and 20 years later, I still have that copy. So I’m a big fan of Clive’s and I love his books. But the first thing I said was, “Don’t do it. I don’t want to do it, and I don’t want you to do it. The book is too great and you Hollywood people … you just keep doing remakes and sequels or movies based on great books or great comics and just mess them up. So don’t it. The story is too great and too untouchable and I don’t believe you got a good script out of it. It’s a short story and it’s hard to make it into a 90-minute movie.”

Gary just laughed and said, “We took a long time working on this script, take it with you, read it and come back in a few days. Just let me know if you like it or not. If you hate it, we’ll look around for something else for you.” So I read it and I was surprised. It was very good. So I went back and said, “I was wrong. I’m impressed. The script needs a little bit of work but … I think I can make a new classic horror movie.” Gary said, “That’s good to know.” So at the next meeting I met Tom Rosenberg [producer of the Oscar- winning Million Dollar Baby]. After three minutes, they said, “That’s it. Let’s make the movie.” So this all came out of the very first meeting my manager set up and it was all set up within a week. So I went back to Japan and started packing up to move to LA. I was back in the US about a month later and we went into preproduction.

When did you first meet Clive Barker?

It was early on in preproduction when I was working hard on the script to make it even better. I went to Clive’s house and we had a lot of discussions. That was another dream come true right there. I never thought 20 years ago when I was reading his book that it was going to be my first Hollywood movie. So it was a very happy day. But when I met him, the first thing I said was, “Clive, you gotta stop letting them make those stupid Hellraiser sequels. They’re destroying you.” And Clive said, “I know, I know. It’s out of my hands.” I said if they asked me to direct one of those, I never would have done it. But this is The Midnight Meat Train. This is the one I’ve been waiting for. I know it’s going to be shit if someone else directs it.” I thought it was a great opportunity to reintroduce Clive Barker. I’m a big movie fan and I collect a lot of action figures to keep in my office and in my house. And it’s always the same characters again and again: Pinhead, the Cenobites, Michael Meyers, Jason Voorhees, Freddy Krueger. But that’s it. I don’t buy figures from Jeepers Creepers or Pumpkinhead, even though I like those movies …

Do you think its just nostalgia for those characters from when you were younger, or do you think there was something genuinely special about that generation of films?

All the influence I have comes from the 80s. I don’t really watch 90s movies over and over again, like I do with 80s films. CGI hadn’t been perfected yet so everything felt more handmade and analog. Because they couldn’t have perfect visual effects, it made filmmakers try harder and to cover their weaknesses with more passion and ideas. But I’m also frustrated that I keep buying special edition DVDs of the same movies and keep buying figures of the same characters … but there is nothing that matches those movies. That’s why there haven’t been any new great horror characters in the 90s and 00s. So I told Clive I wanted the killer in Meat Train, Mahogany [played by Vinnie Jones], to be a new horror icon because that’s what we need.

The video of the Meat Train panel at Comic Con (where Barker goes into an insane rant about pot brownies) is really amazing. Is Clive like that all the time?

You can’t really define what kind of person he is. He’s Clive Barker! The one and only. I can’t be too surprised about what comes out of his mouth or what he does. That’s the guy who creates all those great stories. I knew it was going to be a hard mission to try and visualize what’s in his mind. But that’s why I did this film. I always like to challenge myself.

So once you went into production were there any new challenges you had to face on the set?

It wasn’t that difficult for me. I was expecting a bigger difference between making movies in Japan and in Hollywood. But I was always kind of an outsider in Japan too. It was always hard to make movies there. But here, I felt really happy going into preproduction surrounded by all these experts and a clever and talented crew. The hard times mostly came when we were developing the script. Somehow Clive read one of my in-progress drafts and he got pissed. There was all this stuff missing from it and he didn’t know that I was going to put new stuff in it. Once I explained what I was going to do, we were OK and we got along great. But that was really scary (laughs), making Clive Barker angry! But yeah, it’s not a big budget film so we only have a very limited amount of money and time. One of the producers even told me, “Hey, I’m sorry but this is kind of impossible with the money and time we got. There’s too much stuff in this script.” Now this is a very experienced producer and even he was asking, “How are we going to do this?” (laughs) But we always believed in ourselves so it wasn’t really that hard.

I’ve read interviews with other Japanese filmmakers who go to Hollywood and it seems like they immediately have problems dealing with the system.

Well, if you don’t speak English and if you’ve never lived abroad, it’s going to be much harder. I don’t believe in making movies with a translator. But it’s more about personality. I’m always having problems with the Japanese staff … not the crew, but mainly producers. They don’t do anything challenging, they’re afraid, and they don’t take responsibility. Here, right now I’m editing the film and there are disagreements about lots of things like music with the producer, but I understand that Tom Rosenberg is the guy. He’s the one who gave me this opportunity to do this great project, so I respect him.

What do you think the problems are with the Japanese film industry?

The problem is a lack of producers and directors. That’s it. I like Japanese movies from the 60s to the early 80s, but I’m not a fan of Japanese movies at all now. Now TV has more power than the film industry in Japan. Without their support, a movie can’t be widely released. So whatever I make in Japan has to be based on a best-selling book or manga or TV drama. There’s some of that in Hollywood too, with remakes again and again. So it’s kind of the same everywhere, but in Japan it’s very bad. After Versus, I did Azumi and Sky High (2003), both based on comic books, and of course Godzilla Final Wars. So they were easy to make on the one hand, and really hard on the other. When I originally tried to make Versus, nobody wanted to get involved. I went to see everyone in the Japanese film industry and nobody gave me a chance. Only after Azumi was a hit did everyone start calling me saying I could do whatever I wanted. But still, it had to be based on a book, or manga, or a TV series. Japanese producers are really afraid of doing something original. If you make something based on a comic, you get support from the publisher. You make something based on a TV show, you get support from the TV studio. So this is how film producers kind of lost the war. TV companies have more power now. And those people know nothing about making movies. There’s very little chance for an independent filmmaker in that environment.

It seems like out of all your films, everyone wants to talk about Versus.

Whenever I go to a film festival or convention I find all these Versus freaks out there. They always ask me the same thing: “Is there going to be a sequel.” Like I said, I’m not interested in doing the same thing again. That’s why I said no to doing Azumi 2. I did Meat Train because I’d never done a horror film before. There are horror elements in my other movies, but not like this. It’s not like a Ring-style ghost story. It’s something really different. I always want to do something new and challenge myself. But Versus … I’m always surprised at how popular is it overseas. So after three or four years of experience with those fans, it finally convinced me to go back to Versus again. So I’m writing the script right now for an American version of Versus. It’s going to be something like Evil Dead 2, kind of a remake/sequel. It’s going to be much more insane and extreme in terms of action. The script will be ready in about two months. I don’t know if it’s going to be my next movie. I did good on Meat Train, so I’m talking to lots of producers and studios right now, so I’ll decide soon what I’m going to do next. With Meat Train, my goal from the beginning was to make a new horror classic that’s going to last. So I don’t think I’ll want to do another horror movie right away, unless it’s a super great project. For the next film, I’m thinking it’s got to be a big action movie.

So Meat Train is going to be a straight-ahead horror film?

Of course at the end there’s going to be action. That’s how the original story ends, with a big fight between Leon [Bradley Cooper] and Mahogany, the killer. So why not have a crazy action scene? I think the final fight is going to be a new dimension in fight sequences. It’s so insane. There’s all these dead bodies hanging upside down and blood everywhere and these two guys fighting with everything they got. It’s brutal. It’s going to be a no-mercy movie.

How do you feel about recent no-mercy horror films like Saw and Hostel?

I like those movies, but I don’t think I want to make something like that. I’m not interested in just making a movie about people being tortured for 90 minutes. It has to have characters. That’s why I chose Midnight Meat Train. It’s not just a gross out. It has a great story and characters. But visually, I think it’s going to be the equal of Hostel and Saw. It’s going to be one of the bloodiest movies ever made.

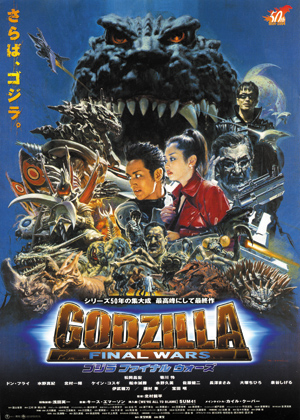

For me, personally, Godzilla Final Wars is my absolute favorite of your films. Can you talk about that period in your career?

It was kind of a tough time for me. I was offered the job right after Azumi and that was a hard movie to make. It was my first big project and it took two years to develop. Before Versus, there really hadn’t been any Japanese action movies for a long time. Since Azumi there’s been all these shit movies like Shinobi and Dororo or whatever. But back then, it was hard to get a big action movie made even with a powerful producer like Mataichiro Yamamoto. Afterward, I thought I was done with making movies in Japan. It was just too hard to make a great movie there because of what I was talking about earlier and because of the whole system. For example, when I was doing Azumi I said I needed six months to train this one actress to be an assassin. But in Japan, talent management companies make their actors and actresses work like horses. They do commercial and TV series every day and they sleep about two hours a night. That’s how they make money. It’s completely different from the system here. I knew asking for six months was unrealistic, but I actually only needed about three months of training for this actress. I mean, we are trying to make a great, great samurai action movie so of course we need some time for training, right?

I never said this before, but in the end they only gave me three f**king days. It wasn’t the actress’s fault; it was all the dirty liars around her. So during preproduction I told her alone, “If a shitty movie comes out, everyone blames the director and the lead. That’s it. Nobody else. You and me have to stay together. They only gave you three days for training, so take your wooden sword with you everywhere you go and practice whenever you can. And after shooting, I have to train you. It’s going to be a hard schedule.” So we woke up at 4 in the morning and shot until 6 pm, went back to the hotel at 7, took a shower, ate something, and after 8, me and my action director trained her. The shoot lasted for three months, so when you watch the film, you’ll see she’s much better at action at the end rather than at the beginning. I’m really proud of that movie, but that was a really weird way to make something.

So afterward, I felt “this is nuts, I’m done with this country.” I’d already been talking to people in Hollywood, so I was ready to get out. But then I got offered Godzilla Final Wars. My friends told me, “Godzilla is a dying series. They don’t make money anymore. Only kids and otaku go to see them. Why would you want to make one of these movies? You’re in a great position now.” I understood what they were saying, but come on. It’s Godzilla! It’s the 50th anniversary and the final movie. It’s a once-in a-lifetime opportunity. I’ll have lots of opportunities to make Hollywood films. That’s my strength. I always have faith in myself. But some people told me, “Hollywood is interested in you now because of Versus and Azumi. If you do a Godzilla movie now, you’re going to miss out on the timing. It’s going to slow you down.” But come on. First of all, if I do a Godzilla movie, I’m going to make it great. Even if it’s a dying series, if I make a great movie somebody will come and watch it and somebody will offer me something else. If I worry too much about whether “this movie is going to make money,” that’s not healthy. All I should care about is if I like the project and if I want to do it. So I decided to make Final Wars and it was a lot of fun. But I was really disappointed that it didn’t do so well in Japan and that the company couldn’t sell it to the States for theatrical release. After Godzilla, it was clear to me that it’s not worth fighting in Japan anymore. I mean they are going to release [Korean monster movie] Dragon Wars in the US, right? Everything depends on things like who is the producer and can he speak English and negotiate with Americans? And unfortunately the producers of Godzilla were very useless.

How about the difference between audiences? I’ve heard that in the US, viewers were standing up and cheering during the monster battles in Final Wars.

I don’t know if it’s because of the education system, but we Japanese are raised so that if everybody is looking to the right, you have to look right too. If nine people agree on something, you have to agree too. Here in the US, you have to have your own opinion, but in Japan, it’s better not to have one. If you open your mouth and say what you really think, people will think you are troublesome. That’s what everyone says about me. You go to Japan and ask all those executives at the studios and 80% will say, “Kitamura is a scary guy. He’s going to punch and kick you.” And I’ve never even met 99% of them. The other 20% love me and that’s the way it goes. That’s because I always open my mouth and say, “What’s wrong with you guys?”

When they first asked me to do Godzilla, I said the same thing I did with Midnight Meat Train, “Why me?” I told them, “Sorry, but I’m an honest man. I don’t go see Godzilla movies anymore. They were great back in the day, but after the 80s, they’re all shit. You guys forget to update and you just keep doing the same thing again and again. And now even kids don’t want to go. They’ve seen The Matrix and Lord of the Rings. You can’t fool them. Of course it looks like a man in a suit! You shoot everything with that bright light! Why can’t you just shoot it more like a Matrix kind of thing? I’m sorry if that’s the direction you guys want to stay in, but I have to tell you that I don’t like it. I never say to my girlfriends, ‘Hey, let’s go check out the new Godzilla movie.’ But if you ask me, that’s the kind of movie I want to make. I want guys 17-20 to say to their girlfriends, ‘Hey, this time Godzilla looks cool. Let’s check it out.'”

The producer said, yes, that’s the kind of movie they wanted to make too, so they hired me. But when it came to doing promotion, all those studio people just decided to put ads only in otaku magazines. So I said, “Come on! Godzilla otaku will come to see this movie anyway. What we need is something new, like a young female audience. You guys tell me you are doing your best, but all the ads I see at the bookstore are in toy magazines, monster movie magazines. That’s it. That’s the audience we already got, so why are you spending money on these kinds of magazines instead of creating a totally new looking poster design and putting it in fashion magazines, even without Godzilla or whatever. That’s why we hired these superstar actors and actresses and you guys are not using them.”

But all these ad people weren’t listening. Their attitude was, “We know what we’re doing.” So I told my producer, “We’re in a minefield here. Those stupid people are going to make every mistake I’ve been telling you about. When the movie comes out, it’s not going to make any money. Then none of them are going to take any responsibility. It’s all going to be on us: the producer and the director. And you’re telling me you can’t fire them?” And he was almost crying at this point and he said, “Still they are the best people we have. That’s the difference between you and us. You are on your own, but we are part of a big company and that’s all we got and I don’t have the power to fire them.” So I thought, “Oh shit, they KNOW they are going to make a mess and still they won’t do anything.” So I said to them during postproduction, “Maybe you should fire me. Get somebody else to finish it.” I wasn’t making a movie to let them ruin it. I knew 1000% that they were going to f**k up and that the movie wasn’t going to make any money, so why waste my time? But the producer just said, “Don’t say that.” So when the movie opened, it didn’t really make any money. It did okay, it wasn’t a big bomb, but okay is not enough for the final Godzilla movie.

Well, now the film is part of a bigger legacy …

That’s why I wanted to do it. With international audiences my three most famous films are, in order of popularity, Versus, Godzilla Final Wars, and Azumi. The overseas audience got what I wanted to do and that gives me energy and I know that I wasn’t wrong. But someone should have done something to get a bigger theatrical release over here. Even Versus and Azumi got released in US theaters, so why couldn’t this big studio make a deal with a Godzilla movie?

So how does your most recent film, LOVEDEATH, fit in with your career path?

I haven’t finished Midnight Meat Train yet, but so far, I think it’s the best movie I’ve ever made. It’s so crazy and too extreme. Which is why we’re still negotiating for overseas releases. The original is 2 hours and 30 minutes, and we need to make a shorter version for foreign sales, especially in the US. There are some people who only look at the numbers, so my agent asked me to cut it down. I did and it still works. But it took me a while. I didn’t make LOVEDEATH for money. If I had it would have been easier to think about the foreign market and the running time before I started shooting. But LOVEDEATH was made from pure desire. I felt like I had to make this movie with my friends in Japan before moving on to the next stage of my career. So I didn’t care or worry about anything else. In Japan, they want the DVD release by the end of this year, but I prefer not to release it so it will become legendary. I’m telling my people in Japan, “In three years, my value is going to go up. So just hide it for now. I’ll put it out when I’m in a good mood.” Like I said, that’s my strength. Believing in myself.

In between films you managed to work on the Metal Gear Solid: Twin Snakes game.

That was a great experience. I did it because I like [game designer] Hideo Kojima-we worked together great. Games are fun, but its more otaku. You work more with drawings and computers. I’m more of a movie guy and I like working with humans, which is what I’m good at. And of course it’s more fun to deal with a real beautiful woman than someone with motion capture devices on their body. I’d prefer to work with a real beautiful girl than a CGI girl. That’s kind of the problem I’m facing now. I want to make a big action movie, but I don’t want to spend three months in green screen.

So what are your feelings on the spread of otaku culture throughout the world?

Twenty years ago when I was a movie otaku in Japan, I never dreamed that Japanese movies and comics would ever be exported like this. It’s good, of course. I get a lot of support from overseas otaku. They are the guys who love my

movies and give me energy. But it’s a little bit sad that anime, manga, and games are the main things expanding Japanese culture over the world, not live-action movies. But if you are in Japan, they say things like, “This is the golden age of Japanese movies,” right? But step outside and … who’s watching? When [big-budget action film] Dororo came out, they announced that it was going to be shown in 50 countries. They’re going to laugh at us if they see that kind of movie! It makes me angry and I feel like I have to do something about it.

So you haven’t given up on Japan?

I still have lots of great people there like my comic artists and my designer. But there are no producers or companies that can introduce them in a good way to a worldwide audience. Maybe only Taka Ichise [producer of The Ring and Ju-on], but that’s Japanese horror movies. Doing the same thing over and over is going to kill us. So I’m producing this samurai-zombie movie that we are going to start shooting in a few months. I wrote the script and the director is my right-hand guy [Ichiro Kiriyama]. He wrote Azumi and Final Wars. I’m doing it because it’s not just another Japanese ghost story; its more direct and bloody. No mysterious phone call, no computer. Everyone is going to get their head chopped off!

You started out as a movie otaku who managed to make it to the director’s chair. What advice do you have for young filmmakers who would like to follow in your footsteps?

Every time I go to conventions, I get a lot of DVDs from these guys who want to be the next Tarantino or the next me. And I watch them, because I’ll feel bad if I don’t, and unfortunately I’ve never met someone who is good, in Japan, the US, or wherever. If they are good, then I’m going to call them and give them a chance. That’s what I’ve done my whole life. I’ll try to make it happen somehow. But there’s a huge difference between being an otaku and being able to please otaku. Just because you’ve watched thousands of action movies doesn’t mean you can make a great action movie, right? That’s tough. And a lot of what I get are bad ripoffs of Versus, which isn’t what people should be doing. I never want to compare myself to someone else. I always try to fight the enemy within. I’m always telling myself, “No, it’s not good enough, you have to try harder, more, more, more.”

I’m in the middle of preproduction right now and I’m also writing four scripts and reading three books and reading four scripts at the same time. I feel like I’m going insane. I’m also working on six other projects with different producers. Every time I meet with them, I have to be prepared, otherwise I don’t get the job. If Clive Barker thinks I’m a dickhead, it doesn’t matter if I’m a fan or not. So if I get respect from Clive, it’s not because he’s a nice person. He sees how hard I’ve been trying with my career and on this movie. So there’s no real advice I can give except: try hard. Do 100% more than your best. I never say negative things to young filmmakers who ask me for advice, but it is extremely hard. But don’t listen to people who tell you never. I’ve been through stormtroops of people who tell me, “No, you can never be a director.” Since I was 17, thousands of people told me, “You never can become a filmmaker.” Then after I became a director, thousands of people told me, “You’re never going to make it to Hollywood.” But I made it because I tried my best.

For more Ryuhei Kitamura, check out our review of his Lupin III live-action adaptation.