“The next Miyazaki.” In an industry seen as slowly drying of talent, perhaps no other person in anime has had this label applied to them more than Makoto Shinkai. This might owe more to his staunchly self-driven, independent approach to animation than to his actual style, having helmed the entirety of his 2002 debut Voices of a Distant Star on a single iMac and taking meticulous control of his larger-staffed works.

However, where Shinkai has consistently fallen short of Miyazaki is in variety. From his debut short Voices to 2008’s 5 Centimeters per Second, the focus has invariably been about high school couples trying to maintain connection through war, distance, parallel universes and/or faulty train service. Soaked in the bittersweet and nostalgic, they are skillfully helmed tearjerkers, but where Miyazaki would take a few familiar themes and shake them up in completely new settings with a few repeated motifs, Shinkai transplants whole plots onto just slightly different locales.

With Children Who Chase Lost Voices from Deep Below, Shinkai’s latest movie (and longest title), one gets the feeling that Shinkai took the Miyazaki comparisons too much to heart. We open in a sleepy mountainous town that can be found anywhere in the Japanese countryside and are introduced to Asuna (Sora no Woto’s Hisako Kanemoto), a precocious elementary schooler who is fascinated by a mysterious blue stone given by her late father.

Using the stone on a jerry-rigged radio tuner, she often goes out to a cliffside to listen to a mysterious song coming from an unknown origin. As fate would have it, the song gets the attention of Shun (Spirited Away’s Miyu Irino), a young boy who comes from a mythical underground kingdom called Agartha and frequently talks about wanting to see the stars above (alluding to the more succinct Japanese title Hoshi wo Ou Kodomo – Children Who Chase Stars). Not long after, a mysterious school teacher, Morisaki (Naruto’s Kazuhiko Inoue), transfers into Asuna’s school and seems to know an awful lot about Argatha, the land where one can have their wishes granted, even bring back someone from the dead…

Using the stone on a jerry-rigged radio tuner, she often goes out to a cliffside to listen to a mysterious song coming from an unknown origin. As fate would have it, the song gets the attention of Shun (Spirited Away’s Miyu Irino), a young boy who comes from a mythical underground kingdom called Agartha and frequently talks about wanting to see the stars above (alluding to the more succinct Japanese title Hoshi wo Ou Kodomo – Children Who Chase Stars). Not long after, a mysterious school teacher, Morisaki (Naruto’s Kazuhiko Inoue), transfers into Asuna’s school and seems to know an awful lot about Argatha, the land where one can have their wishes granted, even bring back someone from the dead…

Through a series of events I will not directly spoil, Asuna comes to realize that her blue stone is a Clavis—a key to enter Agartha. Soon enough, she, Morisaki and Shun’s twin brother Shin find themselves on a perilous trek through Agartha to do just that. Morisaki, in particular, desires to bring his wife back from the dead.

Despite a page in the film’s program pamphlet proclaiming “2 years in the making, but 30 years in the imagining,” it’s hard to shake the distinct Laputa flavor covering everything. The rocky canyons, retro steam trains and obsessed scholars of Asuna’s town would look right at home in Sheeta’s world; whereas the design of the Queztacaotl god-beasts that roam the land of Agartha also look like re-drawn versions of the robots that tended the flying’s castle’s lonely gardens. Plagiarism would be a bit strong, considering Laputa itself is a hodgepodge of Vernes and Swift, but Shinkai is definitely a diss track rapping over a Ghibli beat.

Which is to say that there are several unmistakable Shinkai touches to be found here. Recurring composer Tenmon brings another lovely string-driven score, and art director Takumi Tanji gives us starry skies that would make Van Gogh jealous. Shinkai’s obsession with lighting also becomes a plot device here, with monsters that literally lurk in the shadows and require our heroes to find constant light. The inevitable themes of lost love and regret are also at play here, with Morisaki’s frequent flashbacks to the Georgia-esque war that left him with little time to spend with his sick wife Lisa and Asuna also trying to bring back a lost friend.

It’s in these moments where the movie shines brightest. Morisaki is by far Shinkai’s darkest and most complex character to date. Unlike the quiet milquetoasts of Voices and Centimeters, this man’s grief leads to sometimes rash action instead of quiet introspection. He is intelligent and not without human compassion, but is also a man haunted and jaded to the ways of the world, never afraid to draw his well-maintained pistol in the name of getting his way. Asuna and Shin’s blossoming friendship, similarly, shows a different side to the lovesick teens of those earlier works, as they instead form a trust that has myriad shades of interpretation but never bashes the viewer over the head.

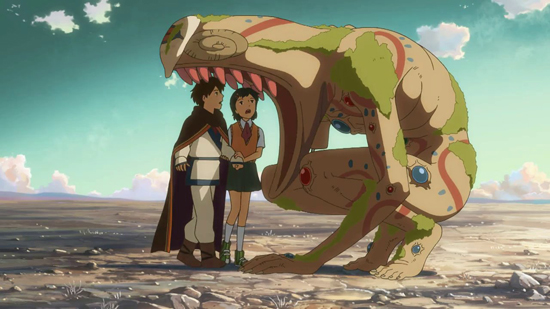

Also commendable is the design aesthetic binding Agartha. Shinkai and company give each locale in Agartha a distinct but cohesive look—something of a cross between Ancient Indian and Latin American fashions and architecture. Also a delight is the nature of the gods that roam the land. Miyazaki often tries to make gods and spirits into likable, or at least relatable, humans with funny shapes and quirky personalities, while Shinkai is content with the unknowable remaining just on the border of psychedelic and beyond human comprehension. The moments they get to shine are brief, but they are memorably nightmarish.

Also commendable is the design aesthetic binding Agartha. Shinkai and company give each locale in Agartha a distinct but cohesive look—something of a cross between Ancient Indian and Latin American fashions and architecture. Also a delight is the nature of the gods that roam the land. Miyazaki often tries to make gods and spirits into likable, or at least relatable, humans with funny shapes and quirky personalities, while Shinkai is content with the unknowable remaining just on the border of psychedelic and beyond human comprehension. The moments they get to shine are brief, but they are memorably nightmarish.

Speaking of nightmares, what was most surprising and what the viewer should be prepared for is the rather frank depiction of violence (perhaps cribbing from Princess Mononoke as well?). After spending the first fifteen minutes or so following Asuna and her peaceful life, it came as a shock to see chop-socky antics between a boy and a massive-jawed beast with copious levels of bloodshed spewing out with every kick and shove. Not to mention the Modern Warfare-style nightvision that kicks in with helicopters and mercenary grunts spraying hails of bullets. I’m totally not making that last part up and it must be seen to be believed.

Ultimately, Children Who Chase Lost Voices from Deep Below comes across not as much as a product of The Next Miyazaki so much as The Old Miyazaki Remixed. That’s not necessarily a bad thing either, given that the final product stands as a pretty decent, occasionally moving action-adventure movie with some compelling characters if watched on its own merits. Time will tell if this more proactive, messier Shinkai is here to stay. Either way, next time hopefully he will bring more of his own ideas to the table.

Fernando Ramos is a Japan correspondent for Otaku USA. His photography can be found at www.mroutside.com.

© Makoto Shinkai / CMMMY