Shinichiro Watanabe (left) and Dai Sato (right).

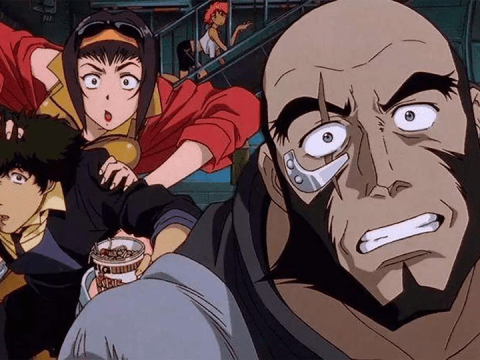

Shinichiro Watanabe (left) and Dai Sato (right).You would be hard-pressed to find an anime fan, casual or serious, who hasn’t come across at least one of the works of Shinichiro Watanabe. Whether it’s his benchmark sci-fi Cowboy Bebop, the hip-hop infused Samurai Champloo, the coming-of-age masterpiece Kids On The Slope, or the simulcast romp Space Dandy, Shinichiro Watanabe’s influence has unmistakably crossed cultures and borders.

Joined by his frequent collaborator and screenwriter Dai Sato (Cowboy Bebop, Space Dandy, Eden of the East), Shinichiro Watanabe and Dai Sato sat down for a roundtable discussion with Otaku USA at the annual Nan Desu Kan convention in Denver, Colorado to talk about their influences, creative processes and thoughts on the constantly changing industry they work in.

Otaku USA: So speaking of returning works, especially with returning to that space feel from Bebop, how was it like to work on Space Dandy?

Shinichiro Watanabe: Cowboy Bebop may have a couple of goofy episodes, but it’s basically a serious story, whereas Space Dandy may have a couple of serious episodes, but it’s basically a goofy story, so the switchover was quite nice. Dai wrote screenplays for me for Cowboy Bebop as well as Space Dandy, and he is much better at doing goofball comedy than serious stories, so I really did rely on him for Space Dandy. If you look at Dai’s filmography you may see a lot of serious titles, but you must not be deceived, I know his true self. (laughs)

Dai Sato: You may or may not know this, but there is a connection between Space Dandy and Cowboy Bebop because in a particular episode of Space Dandy there is an item that is common to Cowboy Bebop. But perhaps you already know about the refrigerator.

Watanabe: The item traveled across a wormhole and across universes. (laughs)

OUSA: Cowboy Bebop was originally broadcast 15 years ago in the US, and there are still people at this convention wearing costumes from that show. Did you anticipate the longevity of it, and how does that make you feel?

Watanabe: I am happy to see fans still remember Bebop. Back when we were making Cowboy Bebop, one thing I told the staff was “let’s make a show that does not feel dated in ten or twenty years,” so I am happy that that has actually taken place. But of course they laughed at me when I said that back then and they said “good luck.”

Sato: And for me actually, Cowboy Bebop was my anime debut as a writer so I’m very glad that I believed everything the director said and told me.

Watanabe: So if Dai had started with a different director and followed his words, his life and career would have been pretty different.

OUSA: Mr. Sato, what inspires most of your work and helps give you the ideas to inspire your writing?

Sato: Well, I hope this comes out right, but we tend to get an order or commission to work on a show in order to promote a particular video game or to promote a merchandise or toy line, so that’s the business side of work, but we start with those kind of impossible premises. It’s quite the challenge to turn that impossibility into something that is entertaining.

A bit more on the creative side, my love is in music and also in architecture, so I draw a lot of inspiration from my love for those. I also love to learn about the people behind the creation of the music and architecture, so those kind of personal lives are also inspiration. Also, when it comes to Mr. Watanabe, he likes to parody a lot of historical figures, so that is something that I also draw my inspiration from.

OUSA: While most of your shows have an overarching narrative, you tend to have an episodic format with self-contained stories within each episode. I was wondering if you could talk about the decision to do that with your shows, especially when that is an increasingly rare occurrence now with storytelling in anime and television.

Sato: Well, we tend to work on shows with ongoing arcs as well as episodic. For my style, if we are doing arcs, I come up with the very overall picture that can be very general and meanwhile the episodes are filled in with depicting the characters.

Watanabe: For me, the storytelling style where there is an ongoing arc on top of episodic storytelling is my favorite style. I like episodic structures because someone could catch the series mid-series and still enjoy the show. For example, I often get the urge to catch a particular American live-action drama, but when I grab the show and it might be say, season six episode eight, and it’s at such an advanced stage of the story, I feel rather discouraged and that I may not be able to follow what is going on.

I also like it when there is a change in the personal dynamics between the characters as the show goes on. I tend to enjoy it when the personal dynamics between two characters are very different between the beginning of the show and the end, and in order to accomplish that it’s much easier if there is an overall story arc.

OUSA: The anime industry has evolved over the years since you started. Have you seen the evolution make it more difficult, or new challenges that you’ve had to face in directing, creating, and writing?

Watanabe: Would you be referring to the technical evolution or the evolution in fan tastes?

OUSA: Both actually, from going from analog to digital, to streaming, to what’s on TV, to simulcast…

Watanabe: Where shall we start? Let’s start with the technical side. For the screenwriter, I believe, the medium doesn’t really matter, be it digital, analog, CG or live-action.

From an artist’s side, digital production has really made it easy. For example, there are a lot of things that would not be possible with the analog production from Cowboy Bebop. Back in the days of Cowboy Bebop, we could only afford maybe up to two minutes of computer graphics, and then we would transfer that CG onto film and the finished result would be an analog product. Compositing digital and analog was the most difficult process, and the colors would not match even if they were the same characters. But since around 2000, all production has been completely digital, color coordination has been pretty complete and there has been a wider freedom of expression we’ve been able to do with digital, so that has been pretty good.

As for the rest of your question, as in changes in fan tastes and broadcast methods, that has been a real issue. The production of anime is quite a money pit. If you read the credits in the closing you will notice that it takes over 200 people to produce one episode, so hand-drawn animation is a very money-intensive task. Back in the 70s and 80s, animated shows were made for a much wider general public so there were many more general corporations that would sponsor general shows.

But since the 1990s, animated shows became geared more towards a deeper and narrower audience, so they became increasingly subsidized by DVD and prerecorded VHS sales. Thanks to that, my shows such as Cowboy Bebop and Samurai Champloo could have creative freedom. However, since the 2000s, there has been a sharp decline in home video sales, so it has been difficult for productions to recoup production costs. Because of that, companies have become increasingly conservative and only venture to make shows that would ensure sales such as moe titles. That has been the issue since around the millennium.

Around that time, I myself had a lot of experimental or adventurous titles that I pitched and pretty much all of them went on hiatus. Basically when I tossed the pitch to companies, the first question back would be, “so, where’s the pretty girl?”

Since the 2010s, I think the industry is still in the middle of renewing and reinventing its process. As far as we are concerned, as long as there is a means to get financing for our shows, there is a means of production, and if streaming is a way to generate financing, I think that is an evolving process going on right now.

Sato: And so for us writers, the technical evolution of production hasn’t changed our business that much, but when it comes to distribution and broadcast, streaming has really affected our work because streaming contains no commercials. The writing of the shows need to be approached completely differently.

For example, in a twenty-minute show, if there is a commercial break, we can use that as a convenient means to change the point in time in the story or change perspectives. But when it comes to streaming shows on Netflix or Hulu, there are no commercial breaks, so traditional commercial break storytelling has to be forsaken in forms of different storytelling styles.

OUSA: What stories do you have about people who have been inspired by you?

Sato: It is interesting to see that there are a lot of people that are entering the anime industry, themselves being inspired to do so because of growing up on anime. At the same time, I feel that that can be a wall sometimes.

A lot of us from my generation tended to draw our inspirations from outside of anime, such as film or different genres, and turned our inspirations into anime. We tend to feel something different when young people say they want to make their shows like previous animation.

Watanabe: For me, I tend to meet a lot of people in the anime industry who tell me they were inspired to go into the industry after they saw Cowboy Bebop, and that is very flattering. However, if you were in high school when you were inspired by Cowboy Bebop, and came into the anime industry, it will take a while for you to establish your own style and then shine in the industry. I think finally now, a lot of the former high school students who were inspired by Cowboy Bebop are at the skill level where they shine in the anime industry, and I am very happy that a lot of them are now helping me out on my shows.

OUSA: What do you two most enjoy about collaborating and working together?

Sato: One thing I get to enjoy working with Mr. Watanabe is that at our production meetings we tend to digress and start talking about what kind of music we are listening to or what movies we watched recently. I don’t get to do that with most other directors so I really cherish that.

Watanabe: During our production meetings we might be seriously talking about work for maybe ten percent of the time and the other 90 percent of the time mostly about music and movies. However, it is often the case that all these off-topic conversations do result in inspiration for our work. I think a lot of our inspiration comes from this idle conversation. It’s often the case that our conversation gets so deep so that the rest of the staff don’t really know what we’re talking about.

Sato: But those are the best times.

OUSA: Mr. Watanabe, you’ve said that you see music as “universal language” and that it’s the most crucial part of the works you create. This question extends to Mr. Sato as well. What role does music take in your creative process and figuring out how to convey a certain message to your audience?

Watanabe: I draw a lot of inspiration for my shows from music. There have been many times when I’ve been listening to music and that music would give me images or ideas for scenes. For example, the inspiration for one of my recent shows, Terror In Resonance, came when I was listening to the band Sigur Rós. When I was listening to Sigur Rós, I got the visual image of two boys standing in the ruins of a destroyed city and that led to the idea of Terror In Resonance. That was the original inspiration and that played out into a whole show. So because of that, we actually went to Iceland to record our music for Terror In Resonance. Sigur Rós themselves would’ve been too expensive, unfortunately.

OUSA: In your shows, specifically Cowboy Bebop, Space Dandy and Samurai Champloo, you seem to have the ability to bend genres and change genres from episode to episode. How do you find that balance and make sure it doesn’t come off jarring to the audience?

Watanabe: Let’s start by saying that the both of us like genre films such as sci-fi or horror. However, if we just imitate genre, we just end up as an imitation and we won’t be able to supersede our inspiration. Sometimes we take on an established genre, but in the middle of the show, cross the genre and show respect, but we also intend to surpass our inspirations. If someone who doesn’t really much respect the genre, doing those sorts of genre-breaking moments, you only end up with something that looks weird, but I believe we do it based on our respect for particular genres so that we come up with something tasteful.

Personally, though, I love works where you can’t tell if it’s supposed to be funny or serious, so my shows are very intentionally made in that way. I often instruct my staff to work on a show to make it so that the audience can’t tell if it’s supposed to be a joke or serious, but a lot of times they just end up being confused. (laughs)

That’s because funny shows are one established genre, serious storytelling is another established genre, but if you walk the tightrope between the two, I think you can break through into a whole new genre.

Sato: Once upon a time, before getting started as a writer, I was a DJ. When you work as a DJ, you take old sounds and new sounds and mix them up together. When you do that, you may not feel like you are creating anything new, but at the same time you are. So when Mr. Watanabe told me that we would be crossing or mixing or tight-roping between genres, I thought it was just like working as a DJ.

Watanabe: He was an old-school techno DJ. (laughs)

Sato: Yes! Only vinyl.

Watanabe: No computers.

Sato: Indeed.