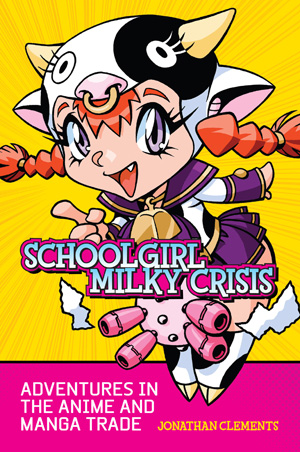

Jonathan Clements knows his anime and manga. He’s helped in the dubbing and translation process, and has even published a few books on the matter, including Schoolgirl Milky Crisis, The Erotic Anime Movie Guide and the Anime Encyclopedia (co-written with Helen McCarthy). But then he’s also published books such as Confucius: A Biography and translated haiku for The Moon in the Pines. Clements told us about how he got so involved with all things Japanese, what he’s working on now, and how he might be an agent from Atlantis.

How did you get started writing about anime and manga?

I was a Japanese major… and Akira came out in 1991… and before I knew where I was, my initial plans to specialize in the Japanese space program were put on permanent hold. I wrote about anime, in an environment where there were so few people who could understand it that I was actually working as a professional translator before I had finished my degree. I was actually late for my final Japanese translation exam because I had been in a studio recording the dub of one of my anime translations… a pretty neat excuse. Better than “I missed the bus.”

What are your books about?

I’ve written about a pirate king, an empress who proclaimed herself a living god, the first emperor of China… all sorts of things. I was also the co-author of the Anime Encyclopedia and the Dorama Encyclopedia, which are the biggest books available on those areas of Japanese pop culture.

https://www.amazon.com/Jonathan-Clements/e/B001IR1BJS/ref=ntt_athr_dp_pel_1

What are your latest releases?

Admiral Togo, about the first Japanese to be on the cover of Time Magazine, the admiral who defeated the Russians in 1905.

The other is a history of the samurai, which is basically a martial history of Japan from the 9th century to the 19th century. Of course, as a feature of my background, I take it into the modern day, with discussion of the samurai in books and films, and odd things like the castle-building program in 1960s Japan, when all those “traditional” castles sprang up, made out of concrete.

What kind of reactions do you get from fans?

There was a woman who proposed marriage to me on Amazon (it’s still up there, in the Anime Encyclopedia reviews); there was someone who accused me of being an agent of the secret kings of Atlantis; there was one idiot who said I tried to indoctrinate his girlfriend into a religious cult (he never said which one). Anime attracts a lot of people at a time in their life where they are still finding themselves, and they are looking for an authority figure to rebel against, and sometimes that’s me. But also there are a lot of very sweet people who just say that I make them laugh or encourage them to think, and that they like hearing my stories about what goes on behind the scenes in the Japanese animation business. And that’s nice.

What books have you published about Japan, but outside of the anime/manga realm?

I wrote a biography of Prince Saionji, who was a prominent Japanese diplomat in the 1910s and 1920s. Very few people have heard of him, and he was an obscure figure even in Japan, where he preferred to keep in the shadows. But he was one of that amazing generation who saw Japan transformed from a “medieval” country into a modern nation, and I find that period from 1850-1950 really fascinating. I’ve also written a book about the Shimabara Rebellion, which was an awful event in 1637 when the samurai massacred thousands of Christians in the south of Japan, in an attempt to wipe out Christianity. That one hasn’t been published yet, though. It’s an amazing story—the rebels were led by a teenage messiah who claimed to have magical powers… I just love it when a true story gets progressively weirder until you start to think it’s fiction. That’s where I am best—telling a story that people think is too good to be true.

Why do you say A Brief History of the Samurai is meant to push the buttons of anime fans and fans of samurai films?

Why do you say A Brief History of the Samurai is meant to push the buttons of anime fans and fans of samurai films?

It’s not that I wrote it for anime fans, but rather that I knew that there were certain figures in Japanese history, like Yoshitsune, Nobunaga or Hideyoshi, who regularly recur in anime. I thought, yes, Masakado’s all over Doomed Megalopolis like a rash, let’s make sure I tell his story. Yes, the Shimabara Rebellion crops up in Ninja Resurrection, let’s make sure I explain what it is. Keanu Reeves is making the 47 Ronin movie—let’s make sure that I include that story in my outline of samurai history. So if you’re an anime fan with a question about samurai history, I have done my best to answer it in that book.

“Samurai film” is a provocative concept. It’s possible to argue, at least at an academic level, that there is no such thing as a “samurai film” in Japan. The very idea is a concept that the Western world has imposed on a whole bunch of movies that the Japanese simply see as period dramas, ninja movies, swordplay films, or even melodramas. Not all swordsmen are samurai; not all samurai are swordsmen. We like to assume that a samurai film is quintessentially Japanese, but often it’s the Western gaze that defines it. In the year that The Seven Samurai scooped up an Oscar, the film that garnered all the awards [in Japan] was an awful, sentimental piece of classroom-melodrama tosh called 24 Eyes. It tells you a lot about the very different ways that we see Japanese films, compared with the way that the Japanese do.

What sort of inside information have you gleaned on anime and manga from all your work?

I think too much of the discussion of anime is in the hands of marketers who just say that everything is wonderful. That’s not actually a victimless crime. It creates false expectations for the medium, and creates a false feedback loop in Japan.

Gaijin critics serve a definite, important role. The Japanese can be so timid, so toothless, so compromised in their criticism, that it’s very difficult finding a Japanese review that calls a spade a spade.

But there comes a time, when talking about anime, when you really stop caring what Dave Bloggs in Indiana thinks, or, I guess, Jonathan Clements in London thinks, and wonder instead what Hayao Miyazaki thinks, or Mamoru Oshii, or whoever. So I like telling stories about things that really happen behind the scenes on anime, stories I have heard from the animators themselves: the cels that were buried in someone’s back garden; the man who backed a truck up to steal the equipment from a bankrupt studio; the conversations that go on in smoky rooms about fan service, or character goods, or cel counts.

Anime is a living, breathing part of the film business, and I like to showcase its real creators. Not just the animators, but every other odd niche of the anime world, from colorists to inbetweeners.

Schoolgirl Milky Crisis has actually grown into a full-on documentary history of anime now. At the moment, I am indexing dozens and dozens of Japanese-language anime industry memoirs and interviews, so I can build up a picture of the whole anime business, told by the people who actually work in it. That’s the subject of my PhD, which I am completing now, and it will also be published as a book, an industrial history of Japanese animation that the British Film Institute will be publishing in 2012.

Once that’s done, I am going to publish a very dull book that only 20 people will read, and it will be called something like “A Preliminary Concordance to Japanese Books About Japanese Animation”. Hardly any books about anime have proper indexes, so I have had to write my own as part of my research. But once you have, say, all the times that Star of the Giants has been mentioned by animators, indexed and ready to hand, or access to every time someone has mentioned Gigantor, all sorts of amazing connections come to light. You can also verify the claims of the Japanese by comparing stories from two animators who work on the same production. And that’s going to make a big difference to people who write about anime for a living.