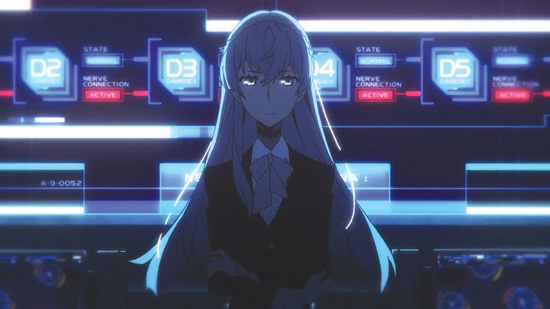

A city built on reclaimed land is really an experiment involving the Kizuna System, which connects participants, or kiznaivers, to each other through their wounds. Once a wound is suffered by one, its pain and associated degree of energy drain are distributed evenly among all others who bear the tell-tale jagged, red mark. Each in the current batch of kiznaivers is said to represent one of the seven deadly sins. These people were chosen because they should not be able to care about/understand each other, but if the Kizuna System can make them do so by forcing all of them to literally feel each other’s pain, then maybe, on a larger scale, world peace wouldn’t be such a pipe dream after all.

The title, Kiznaiver, is a pun/portmanteau of “kizu” (wound), “kizuna” (bond), and naïve (anigamers.com, “Three-Episode Test: Evan’s Spring 2016”), which suits the show’s premise to a T given that all the experiment’s subjects are high school boys and girls. It’s nice to see the usual archetypes and associated tropes applied to something greater; all that high school angst and emotional oversensitivity that causes so much turbulence during the formative years represents the greatest hurdle humanity faces toward sympathy: pride. And, really, what nation comes to mind first when thinking about pride and maintaining a reserved public face more so than Japan?

Kiznaiver goes out of its way to invoke and twist the seven deadly sins to fit taboos regarding Japanese working connections: “The Cunning Normal,” “High-and-Mighty,” “Goody-Two-Shoes” (alt: “Annoyingly Self-Righteous”), “The Eccentric Headcase,” “The Imbecile,” “The Musclehead Thug,” and “Immoral.” By doing so, this story, written by Mari Okada (Toradora, anohana), makes a statement about society suffering from a lack of real connections between real people. It is, as all art tries to be, its own Kizuna System—a means by which to reach out to an audience and make the people therein think beyond themselves in order to identify with a specific character/situation. It’s what poet Percy Shelley deemed the sympathetic imagination, and that’s the main theme of the series; characters and their actions/reactions often speak to the salve of “finding themselves in others” or the resulting irritation/agitation when they cannot. But don’t worry, there’s no need to dust off your Romantic poetry textbooks to enjoy this series.

Outstanding animation production value via TRIGGER makes Kiznaiver as single-sitting consumable as a family-sized bag of your favorite snack. It’s one of those shows that, even if personal investment seems to wane, the sheer beauty of it all won’t let you stop watching. In addition to sharp character designs, dynamic styling via silhouettes and shadow, and in-your-face camera tactics, simple things, say watching characters walk mottled by sunlight passing through the tree leaves above, are mesmerizingly realistic and astoundingly rendered. (I can’t tell you how many times I lost track of dialogue because I couldn’t take my eyes off of how a moving shadow interacts with its environment.) There’s also an element of the absurd implemented via city mascot Gomorin, whose suit-wearers also bear the duty of doing the dirty work for the Kizuna Committee.

With one such scene, it was love at first episode; a bunch of Gomorin—think a two-high pile of perpendicular dumplings with arms, legs, fish eyes, a tail, and a huge X branded over a face crowned with a nest of eggs—wildly gurney a kiznaiver through the corridors of an underground hospital discotheque with pink polka dot lighting and gypsy guitar-infused trance background music. It is amazingly weird and out of the blue and increases the want for whatever may come next. And though the sporadic appearance and varied implementations of Gomorin keep things interesting, the evolution behind the main concept is what married me, heart and mind, to the show.

Before it aired, the premise of Kiznaiver promised a connection between adolescents through wounds. My mind immediately thought emotional trauma, a la Kokoro Connect, but the matter-of-fact of this series, as it turns out, is that the bond links physical pain. The series offers a fun twist on this with the seventh kiznaiver’s “introduction,” but the real draw occurs via a masterful bit of storyboarding and audio around midway through the show. Unfortunately, the plot, including the later-revealed origin story, ultimately dissolves into a predictable (albeit self-acknowledged) pandering to love

triangles and other tropes. (As a sucker for a good bit of jealousy amid the unrequited and a fan of misunderstandings/manipulations, I’m not complaining.) Whether the writing turns this into something useful, instead of using conditions as they are as a simple path to the end of the story, however, is the audience’s call.

According to the powers that be, all these kids have to do to relieve themselves of their painful bond is survive summer (“the season of youth”) vacation while tasked with such horrendous challenges as talking honestly with one another. (Did I mention this is a series blatantly critical of reserved expression?) Ironically, this experiment actually ends up endangering/severing all of the kiznaivers’ other ties (separating them from their “sins”) so they can focus on each other and, in doing so, grow as individuals. As almost no one in the group is originally shown as having close friends to begin with, however, the effect is dramatically lessened but not so easily dismissible.

A character introduction-driven OP, backed by floating, lulling “Lay Your Hands on Me” by Boom Boom Satellites, is a little like falling down a rabbit’s hole; the kaleidoscopic whirling of light and color keeps eyes centered on smoothly moving portraits of the main cast. It’s quite beautiful. Each time viewing it feels like a portal into another world and other selves. The ED is no less impressive if only for its use of flowers to hint at the female characters’ attributes and how they might affect their characters’ roles in the series.(www.formeinfullbloom.wordpress.com, “The Flower Language of the Kiznaiver Women”).

Kiznaiver emphasizes openness for all its hurtful but ultimately helpful honesty in the name of progressing as responsible social creatures. A lot of effort went into making a series that focuses, visually and contextually, on characters forced to focus on others’ situations and feelings. This spoonful of TRIGGER that helps the Okada go down seems a good and necessary chemistry for communal medicine. The anti-apathy message is anything but subtle, but watching everything transpire is as fun as it is tonally gripping and convincing.