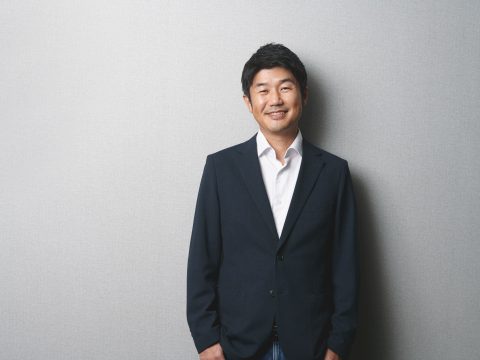

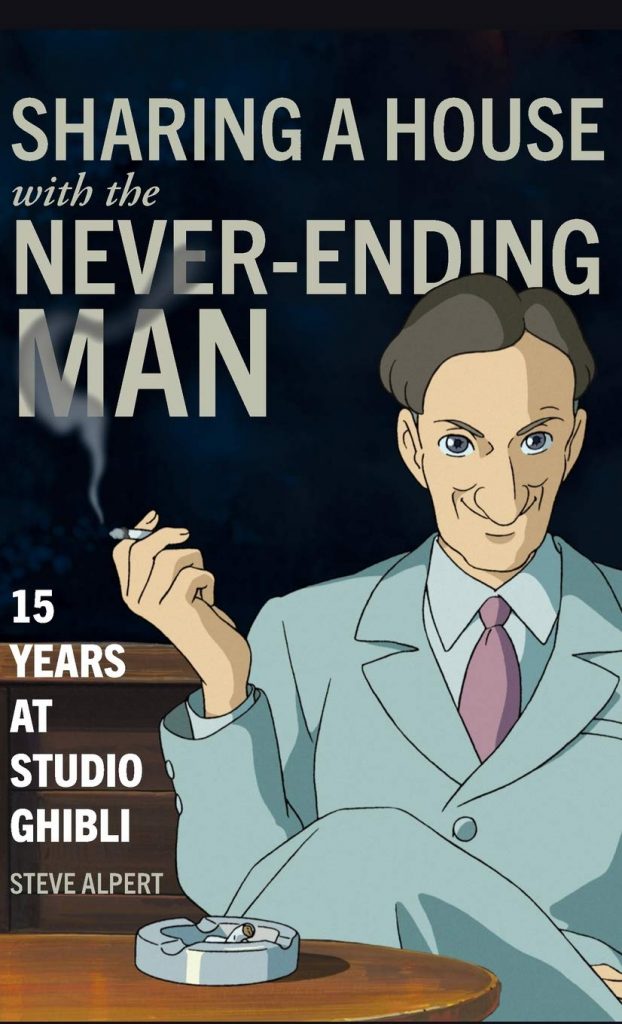

North American fans of Studio Ghibli can thank Steve Alpert for his tireless efforts bringing the beloved movies to a wider audience. Alpert explains his important role as the resident gaijin (foreigner) at Studio Ghibli in his memoir Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man, where he covers everything from Miyazaki’s habits to Disney challenges to what it’s like working as an American in a Japanese company. His next book, Kyoto Stories, will come out in 2022 and talk about his student days in Kyoto, immortalizing his experiences and aspects of Japan that he’s seen disappear over the years.

North American fans of Studio Ghibli can thank Steve Alpert for his tireless efforts bringing the beloved movies to a wider audience. Alpert explains his important role as the resident gaijin (foreigner) at Studio Ghibli in his memoir Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man, where he covers everything from Miyazaki’s habits to Disney challenges to what it’s like working as an American in a Japanese company. His next book, Kyoto Stories, will come out in 2022 and talk about his student days in Kyoto, immortalizing his experiences and aspects of Japan that he’s seen disappear over the years.

He was also the artistic inspiration for the character Hans Castorp (based on the real-life Richard Sorge) in Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises, and supplied the voice for the character in the Japanese version. Alpert talked to Otaku USA about fist fights over translations, art versus commerce, and how Miyazaki made fun of him for wearing shorts by putting it in a movie.

For people who haven’t read your book yet, can you tell us what you did at Studio Ghibli?

I was the head of international distribution and I translated all the films.

You did more than that. You really helped get them out there.

Yes. That’s just false modesty.

One of the things I thought was really interesting in your book was talking about the difficulties of translating, whether it’s for dubbing or subtitling. Can you talk more about the challenges of this?

Translating from Japanese is really difficult. I talk about this in the book. There are all kinds of different levels of difficulty. Let’s say you’re doing subtitles for a film. You’re limited in the amount of space you have. So the translation has to fit the space. And Japanese and English are so different. Japanese is often much longer than English, so you really struggle to make the translation right and make it fit.

I mention in the book an example from Princess Mononoke. There’s a line in the film: “Kabuto kubi da!” The hero Ashitaka is observing the battle and one of the samurai yells that at him. Literally it means, “The helmet is a neck,” which doesn’t make any sense, so you can’t translate it like that. In those days, in samurai battle, they cut off the guy’s head and they could get a bounty. So he’s saying, “If you cut off that guy’s head, you get a bounty.” It’s difficult to express in English, and it’s difficult to express in seven different beats. So you have to find a way to do that. However you do that, you’re going to have to leave something out. That is one problem you have. You do a translation that you know is not the best translation you want, but you have to settle for it because it’s the only one that will fit.

If you’re fastidious and OCD about doing the translations as I am, you’re unhappy with it, but it’s the best you can do in the situation. Any translation is going to be an adaptation. Miyazaki will say something, and if there are five different people listening to him, they’ll have five different opinions on what he meant. And that’s because Japanese is really vague. I remember we were translating the lyrics for this song for Ponyo and we couldn’t agree on who was the speaker. So we had to get the person who wrote the song, and it turned out none of us were right. You do your best. [laughs]

For Howl’s Moving Castle, we had to translate it into Italian for the Venice Film Festival, and the film hadn’t been released in Japan yet. So we couldn’t send the original documents out of the studio, and we got a team of Italian translators to work in Studio Ghibli under security conditions. We actually had to break up fist fights between the translators because they were arguing, “No, this isn’t how you say it! You say it like this!” Translating is thankless because people will always point out what they got wrong.

How involved were the people at Ghibli in your book?

The book was published by Ghibli in serial form in a magazine to begin with. [Toshio] Suzuki-san [the cofounder of Studio Ghibli] read it and various people vetted it for accuracy.

Why did they want you to write this book?

Let me step back. I had always wanted to write a book about what it’s like to be a foreigner, a gaijin, in Japan, working for a really Japanese company. That was my original idea. The other part of it was that I saw so much and was so privileged to be behind the scenes. I wanted to record a lot of it. It’s a dual purpose exercise. Personal recollections and trying to explain what it’s like to be a gaijin, but also everything that happened in getting Studio Ghibli’s films distributed abroad. Japanese are always interested in how foreigners view them, so that was an interesting thing to [the people at Ghibli], but also they were happy to have the whole process of releasing Ghibli’s films documented from my point-of-view.

Has the reaction to your book been different in Japan and in America?

Good question. For one thing, when you’re talking about being a gaijin in Japan, Japanese people are really interested. Most of the reaction I got was about the Ghibli stuff. But I didn’t get a lot of reaction on the Japan side, of what it’s like to work in a Japanese company.

I tried to cover a lot of ground. Also, I think the contrast between Disney and Ghibli and the way things are done . . . I tried to talk about that.

Like the cultural differences, with Disney not wanting some things to come out for kids?

Yeah, that was a surprise to me. Also a disappointment. I would say they did everything they could to make the films not look Japanese, or not be seen as Japanese. Since I lived in Japan for 30, 35 years I have a different perspective. But the timing was when people seemed to really be getting interested in Japan. But Disney is a big company, and there are a lot of different types who work at Disney, and I think the people we happened to be dealing with were a lot more domestic and conservative than we’d worked with in Japan.

How do you think they tried to take the Japanese tone out of it?

For example, if you look at the package art, you can see exactly what they were thinking. The fact they felt they had to change it and not use the actual images from the film, I think it says a lot right there.

Do you think it would have made a difference if they’d used the images from the original?

I think so. I think if you’re doing something and you don’t know what the result is going to be and it’s about succeeding or failing, if you’re going to fail, you’d fail doing what you think is right, not what you’re worried someone else might think. I think that’s really the difference in the approach. When I say the people were conservative, they had their own tried and trusted ways of doing things and they don’t like to depart from that with marketing and distribution.

I’ve heard the conspiracy theory aspect where people think Disney did it on purpose because they didn’t like the idea that Ghibli films would compete with their films. I don’t think that’s true. They may have felt that way, but I don’t think they’d make that their method of operation. I don’t think.

Are you still involved with any work with Studio Ghibli?

Yes.

Are you allowed to say anything about it?

No.

I also wanted to talk to you about your role in The Wind Rises.

Oh, thank you.

How did that come about?

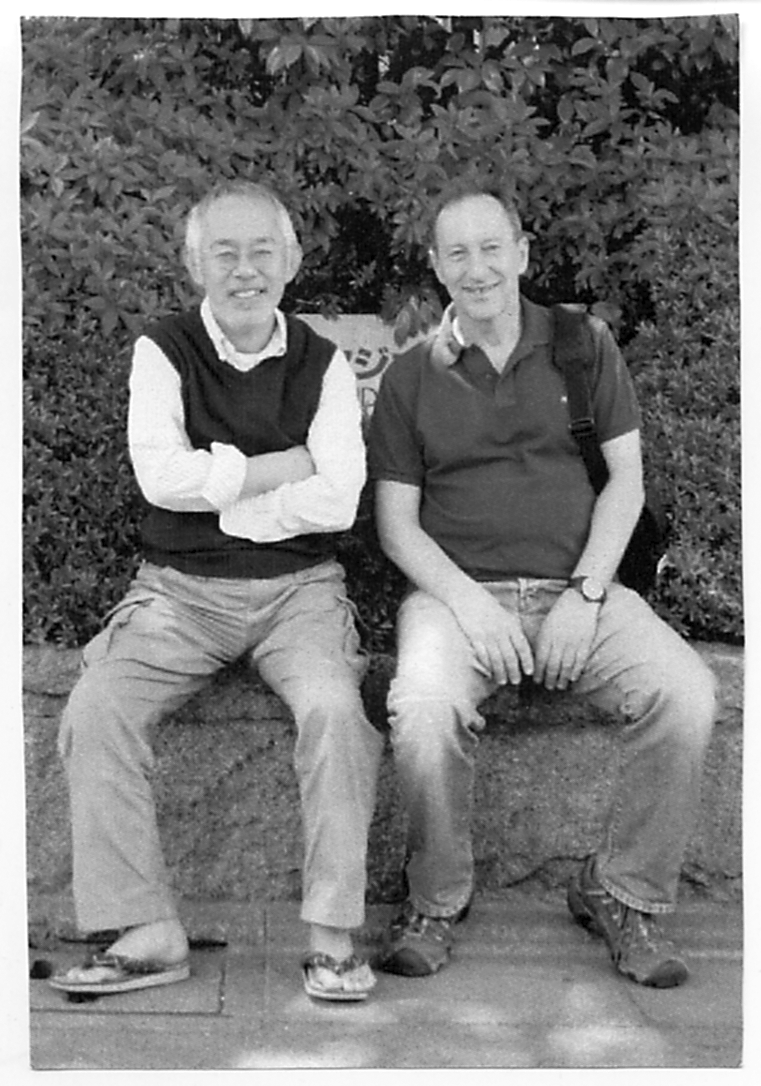

So the character is based on an actual guy, Richard Sorge. He was a spy during the pre-war period. He was Russian and Polish, and he was embedded in the German embassy in Tokyo. Hayao Miyazaki thought of this guy as me. My ethnic background is Russian and Polish. To take it a step back further, I got the title of the book Sharing a House with the Never-Ending Man based on the NHK documentary of that name. I watched this on the internet, and I thought, That’s exactly what it felt like for me to be there. Like a camera. I just watched everything. I didn’t usually say that much. I was just this guy who sat there quietly and took everything in. I think Miyazaki thought of me as a spy, and thought I would be perfect for the role. It wasn’t just me, but most of the people who had a role in that film were people he knows. He was taking people from his life who he matched up with characters in the film. Even as he developed the film, that’s how he thought of the characters.

There’s even a scene in the film where he makes fun of me. The one where I’m running around wearing shorts trying to catch the paper planes. At the studio at lunch time, during the summer, I’d change into shorts and walk into the next town to have lunch to try to get exercise. So he was making fun of me for wearing shorts at the studio. I think he got my nose a little big, but other than that . . . He wanted me to be the voice and not just the model for the character.

In the Japanese version.

They offered to have me do it in the English version. But I didn’t want to. I thought they should get a professional voice actor for that.

Did you ever expect him to make you into a character?

No. No. It was a little scary to do the voice. I’m pretty familiar with the recording process since I’ve supervised a lot of them. I know how it goes. It’s a plus and a minus. It’s a plus because you know how it goes and a minus because you know how hard it is. It’s hard to say No to an opportunity like that. Plus his language . . . his language is so beautiful and poetic. The lines he gives you to say that no one has uttered in fifty or sixty years or more. These words you’ve never heard of, really long, tongue-twisting words.

It stuck out to me that Castorp’s a minor character but he has such an important role because he’s the one who warns Jiro about the Nazis.

Well, he’s anti-Nazi. He was a spy against the Germans, actually. Interesting. Good for my character.

I’ll tell you this. You may find it interesting. I had to sing a song in German. I don’t speak German. And I’m completely tone deaf. That was the low point in the recording session, as expected. This is an example of how Hayao Miyazaki thinks. The point of that song was that this was an actual song that became popular in Germany. And as it happened, the woman who sang the song was secretly Jewish. She was a favorite of the Nazis but they didn’t know she was Jewish. The song became a huge hit during the war and just before the war. The character sings it in the movie and asks other people to join in because anyone who knew the song would had to have been in Germany recently to know it. That’s how he found out that the Japanese aviation technicians and engineers had been to Germany and were cooperating with the Germans, because they were able to sing this popular song. Isn’t that amazing? And if you watch the movie, I don’t think there’s any way to figure that out. But Miyazaki explained that to me, so that’s how I know the point of it.

Did Miyazaki know she was secretly Jewish?

I don’t know. Probably not, but you never know what he knows.

Are you Jewish?

Yeah.

So it’s Jewish actor [Alpert in the Japanese version] warning the characters about the Nazis.

Ohhh, you’re right. But as far as I know, Richard Sorge who the character is based on, wasn’t Jewish.

Other than being an example of mixed Russian and Polish ancestry, possibly the only reason Miyazaki-san wanted me to do the role was because I was the only one in the studio who had read The Magic Mountain and got the reference to the name, Castorp. He showed me the character for the first time and said, “This is Castorp.” I said, “Oh, Der Zauberberg [The Magic Mountain].” So there you go.

So what do you want readers to take away from your book?

I wrote the book because I wanted to document the extraordinary Ghibli things that went on, the difference between Ghibli and Disney and Japanese and American culture, and what it’s like working in a Japanese company and how funny it is in a way. And then all the things that went on to get Studio Ghibli’s films distributed outside of Japan, which was a lot harder than I thought it would be. I think it’s about the pursuit of art as opposed to commerce. Studio Ghibli is all about art. And the movie business is pretty much all about commerce. When you think about films and movies, big budget commercial movies are movies and Studio Ghibli movies are movies, but they’re completely different. One is the pursuit of a very specific kind of art, and one is art attached to commerce. Even the worst movies, anything by Michael Bay for example, that’s the worst to me, but it makes a lot of money. Art films obviously don’t make a lot of money and it’s more difficult to get them distributed.

So you helped distribute really pure, artistic films bigger than they usually get.

Yeah. I guess I should feel good about that. [laughs]

____

Danica Davidson is the author of the bestselling Manga Art for Beginners with artist Melanie Westin, and its sequel, Manga Art for Intermediates, with professional Japanese mangaka Rena Saiya. Check out her other comics and books at www.danicadavidson.com.